Best Alien Planet Weather Map Ever Reveals a Scorching World

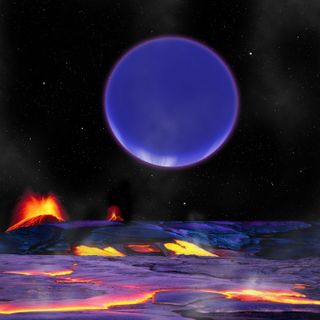

A super-hot planet 260 light-years from Earth is showing signs of water vapor in its atmosphere, despite scorching temperatures that are hot enough to melt steel, according to the best weather map ever created of an alien world.

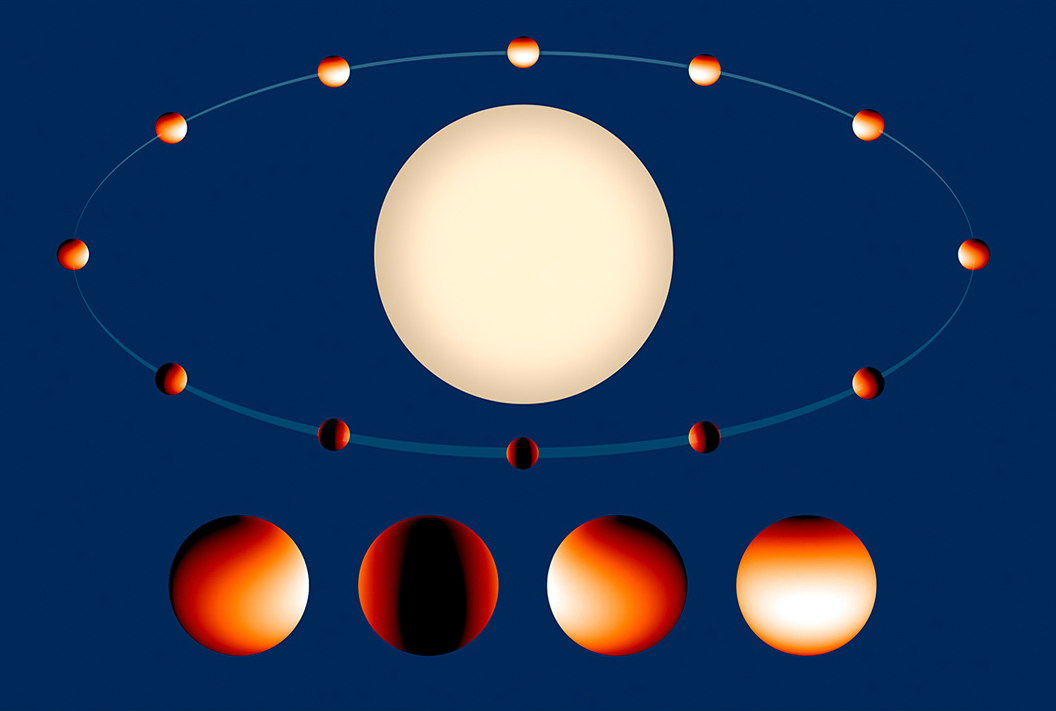

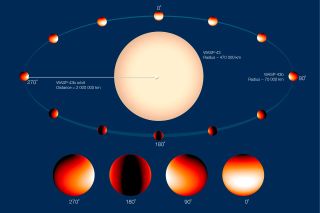

The Jupiter-size alien planet, called WASP-43b, is so hot that daytime temperatures reach 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,648 degrees Celsius). At night, it's a bit cooler — about 1,000 F (537 C) — still hot enough to melt silver.

"WASP-43b is extreme in many ways," study co-author Jean-Michel Désert, of the University of Colorado Boulder, said in statement. "It's the size of Jupiter with twice its mass. Its orbit around its host star, called an orange dwarf, takes only about 19 hours, the blink of an eye compared to the 365 days it takes Earth to orbit the sun." [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

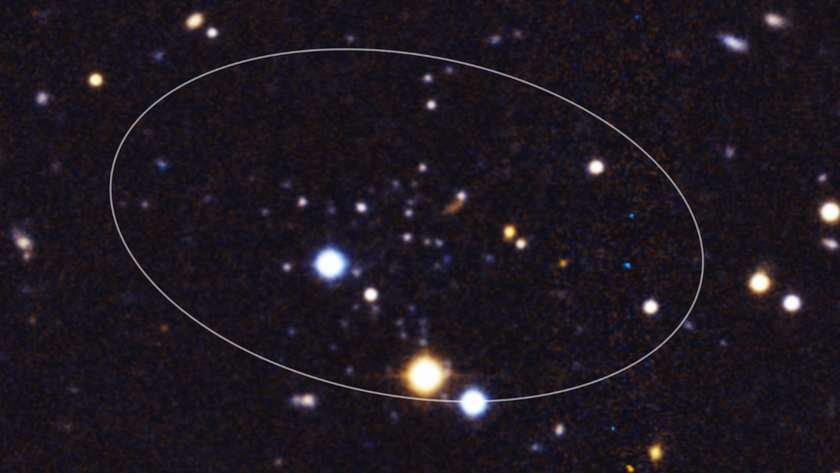

Scientists used the Hubble Space Telescope to create the global temperature map for WASP-43B, and say it is the best one yet recorded. It shows variations by altitude and will be useful when one day the instruments exist to seek water vapor and other signs of habitability in smaller, Earth-sizeplanets, researchers said.

"The big picture is by making these precise measurements of thermal structure and abundance of chemical species [in the atmosphere], it becomes useful to do comparative studies amongst the planets outside our solar system," study co-author Jacob Bean at University of Chicago told Space.com.

The WASP-43b global temperature map research is detailed in tomorrow's Oct. 10 edition of the journal Science. The study was led by astronomer Kevin Stevenson of the University of Chicago and included a dozen researchers from different universities and research institutions. The planet's water vapor content appeared in a separate paper in the Sept. 12 edition of the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Poor temperature circulation

WASP-43b is a planet of extremes. It orbits so close to its parent star — inside the equivalent of Mercury's orbit — that it takes only 0.8 Earth days to whip around its star. Winds on the planet travel faster than the speed of sound, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

How the planet got so close to its star is a mystery. The abundance of water vapor in its atmosphere (which would evaporate close to a star during its formation) shows it must have formed somewhere close to Jupiter's orbit, and then drifted inwards.

"These observations allow us to determine the abundance of water in the planet's atmosphere, which is a major element involved in planetary formation," Désert said in the statement. "By measuring the composition of this planet, we will have a better idea where it formed within the proto-planetary disk of the host star."

Some gravitational influence such as a passing star or planet might have nudged it right next to the star, Bean said.

The planet's proximity to its host star — which is 70 percent the size of the sun — implies that WASP-43b is tidally locked. This means that over time, the star's gravity influenced one side of the planet to perpetually face the star. (That is a phenomenon observers of Earth's moon notice, since one side is always facing the planet.) The star's massive gravity also circularized the orbit over time.

This shows that there is some process making it difficult to distribute temperatures evenly across the atmosphere of WASP-43b, researchers said. Bean speculates it could be the larger mass of the planet compared to others studied, or its fast rotation, but more studies will be needed.

WASP-43b and water

The team performed three days of observations with the Hubble Space Telescope in November 2013, watching the planet cycle through at least three of its "days" almost consecutively. (In between each planetary rotation, Hubble would take a six-hour timeout for other science projects before returning to observing WASP-43b, Bean said.)

While the planet presents several mysteries to exoplanet researchers, one encouraging aspect is how closely the planetary atmosphere matches with the composition of its host star, compared to models of how hot Jupiters are created.

Stars and planets form from the same nebula of gas and dust, with both the star and huge planets pulling in a lot of gas for their formation. WASP-43b's atmosphere is hot, but the amount of water vapor shows a similarity to the elemental abundance of the star, particularly in hydrogen and oxygen (which water is made of.)

"What we're looking for is slight enhancements or depletion of water," Bean said, explaining that an exoplanet the size of Jupiter is expected to show a slight abundance in metallicity, or the proportion of elements other than helium or hydrogen in its composition. More massive planets have less metallicity variation compared with their host star, something that was seen exactly in WASP 43-b.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.