Glowing Results: Rampant Star Birth Left Universal Imprint

There's an intriguing glow across the universe that astronomers have been trying to pin down for years. Recent observations appear to have found the source: compact galaxies in the early universe that were generating stars at a furious pace.

The diffuse radiance is a certain type of so-called background radiation that is everywhere in space but, until recent years seemed to come from no specific locations. In this case, it is a wavelength of radiation half a millimeter long that straddles the high end of the radio spectrum and the low end of the infrared.

Background radiation can be likened to the first and faint glow of dawn, when the Sun is not visible but Earth's atmosphere is infused with a hint of light. The submillimeter background infuses all of the cosmos.

Similar cosmic backgrounds exist at other wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, including infrared and ultraviolet light.

Among the more interesting of the background glows is the cosmic microwave background, the remains of radiation unleashed just 380 million years or so after the theoretical Big Bang. It serves as the only glimpse to that early epoch of the universe. Pioneering observations in the 1960s suggested a known X-ray background, too, was the result of many individual sources, and by the year 2000 the case was closed.

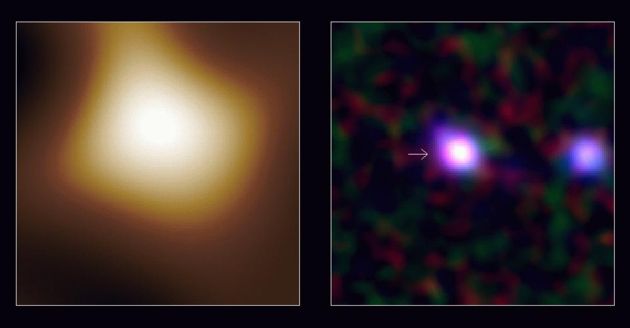

The submillimeter background had been loosely linked to distant galaxies surveyed by the SCUBA camera (Sub-millimeter Common User Bolometer Array) on the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii. But the galaxies had not been located precisely. Instead they were associated with bright areas in fuzzy images -- astronomical observations just beyond the limits of resolution.

New observations with NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope pinpointed the submillimeter-emitting galaxies in the SCUBA images by noting their emissions in infrared, too.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We've known all along that they had to be far away and rapidly turning all their gas into stars, but now we know their true distances and ages," said Steve Willner of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Willner told SPACE.com that each of the galaxies is small yet has an enormous rate of star formation.

"These galaxies are less massive than the Milky Way and yet they are forming stars at least 10 times faster than the Milky Way," he said.

Having precisely located the galaxies, he said, would now allow closer scrutiny. And because each of the galaxies represents a baby picture of the Milky Way, astronomers could learn something about galactic evolution.

The average SCUBA galaxy now nailed down is seen when the universe was about 2.7 billion years old. It is about 13.7 billion years old now.

"The SCUBA galaxies probably represent the earliest stages of star formation in galaxies that will end up being like the Milky Way," Willner said.

Astronomers from the University of Kent, the Royal Observatory Edinburgh and the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom also worked on the study. The results will be detailed in a special supplement to the Astrophysical Journal in September.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rob has been producing internet content since the mid-1990s. He was a writer, editor and Director of Site Operations at Space.com starting in 1999. He served as Managing Editor of LiveScience since its launch in 2004. He then oversaw news operations for the Space.com's then-parent company TechMediaNetwork's growing suite of technology, science and business news sites. Prior to joining the company, Rob was an editor at The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. He has a journalism degree from Humboldt State University in California, is an author and also writes for Medium.