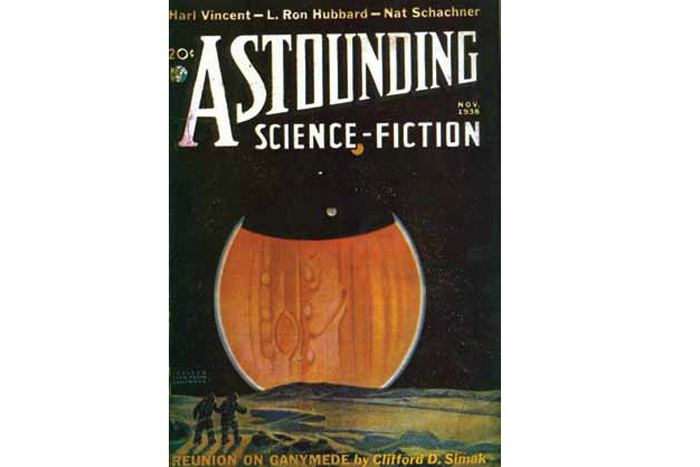

'The Art of Space' (US 2014): Book Excerpt

Apollo artist

The third astronaut-artist is American Alan Bean, who took art classes at night while working as a test pilot for the US Navy in 1962. He became a member of the astronaut corps in 1963 and was a member of the Apollo 12 mission that made the second manned landing on the moon in 1969. Bean flew into space again in 1973, when he spent 59 days aboard the Skylab 2 space station. Too busy during these years to pursue his art, he resumed his studies in the 1970s. When he resigned from NASA in 1981, Bean took up painting professionally, specializing in scenes of lunar exploration based on his own experiences and observations. He also did extensive research. Interviewing Neil Armstrong, Ed Mitchell, Gene Cernan, and many others among his fellow Apollo astronauts, he tried to find out how they perceived things such as color of lunar soil and rocks. "When I talked with Neil Armstrong," says Bean, "he remembered the moon as being a sort of brownish tan downsun, a darker brown upsun, and a gray-brown cross-sun.”

The Great Moon Hoax

First published in the New York Sun newspaper on August 25, 1835, the Great Moon Hoax did not involve actual space travel — but it did create enormous excitement about the possibility of life on other worlds. It would also prove a major influence on the great American writer Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849).

Super telescope

The hoax was a series of sensational articles created by reporter Richards Adams Locke, in which he told of the startling discoveries being made by the famed British astronomer Sir John Herschel at his observatory at the Cape of Good Hope, in South Africa. (Herschel was actually in South Africa at the time, albeit completely unaware of the sensation his "discoveries" were making.) Through the use of a super-telescope built on entirely new principles, Herschel had supposedly found that there were not only living creatures on the moon, but that they were humanoid, fur-covered, bat-winged beings. Locke larded his serialized account with so much detail and scientific-sounding jargon that not only were his American readers absolutely convinced of the reality of his reports, but the news quickly spread to Europe, where it was translated and reprinted in French, German, and Italian, inspiring numerous artists to create prints and lithographs showing the imaginary discoveries in great detail — although some of this interest may perhaps have owed something to the reported presence of nude moon-maidens. The Sun finally confessed the whole thing as a hoax on September 16. When Herschel finally arrived back home and learned how his name and reputation had been so freely used, he took it with great good grace and humor, remarking that his only regret was that he would never be able to live up to the fame.

Italian inspiration

The hoax became enormously popular in Europe, particularly in Italy. It was the inspiration for a large number of engravings and lithographs based on Locke's descriptions of the lunar landscape and its inhabitants, such as Scoperte fatte nella Luna dal sig.r Herschell (Lunar Discoveries Made by Signor Herschell), a suite of four lithos published anonymously in Naples; Delle scoperte fatte nella Luna dal Dottor Giovanni Herschell (Of the Lunar Discoveries Made by Dr. John Herschell), an engraving published in Naples; Nuove cose e cose nuovissime nella Luna e sulla Terra (New Things on the Moon and the Earth) by "Sir Causticolo Oestro"; Delle scoperte fatte nella Luna dal signor Herschell (Of the Lunar Discoveries Made by Signor John Herschell); Scoperte fatte nella Luna dal Signor Herschell (Lunar Discoveries Made by Signor Herschell) by Michele Clapié, Turin; and Altre scoverte fatte nella Luna (More Discoveries Made on the Moon).

Hot air

But there was at least one person with cause not to see the funny side of Locke's joke. Just two months before his lurid tales of nude moon-maidens had hit the newspaper stands, the Southern Literary Messenger had published its own hoax story of space travel: "Hans Phaall — A Tale," by Edgar Allan Poe. In Poe's account, Phaall traveled in a hot-air balloon to the moon, where he spent five years living among "lunarians." However, the satirical tone of the article meant that readers were quick to see through it, and the Great Moon Hoax would soon eclipse Poe's efforts. Undeterred, in 1844 Poe wrote another series of "factual" articles — again in the New York Sun — describing how a European balloonist named Monck Mason had crossed the Atlantic Ocean in a hot-air balloon flight lasting three days. Like Locke's work before him, "The Balloon-Hoax" was a work of pure fiction — although a markedly less successful one, with the story's retraction following just two days later.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.