Could There Be Organic Matter on Mars?

The origins of organic matter found by Mars lander missions have long been debated, but a new study suggests a way to find out whether these chemicals of life came from the Red Planet or elsewhere.

Several Mars lander missions have detected chloromethane, a chemical sometimes produced by living organisms, but most scientists think the findings were contamination from Earth.

Now, a team of researchers has replicated these experiments on a meteorite found on Earth, and found that it produced chloromethane from organic materials contained in the space rock. The findings suggest the chloromethane on Mars may have come from meteorite debris on the planet's surface or the Martian soil itself, rather than from Earth. [The Search for Life on Mars (Photo Timeline)]

More recently, NASA's Curiosity rover found traces of chloromethane in soil heated in one of its own chemistry instruments. Again, researchers claimed the chemicals were nothing more than terrestrial contamination, partly because it wasn't clear whether such chemicals could form on their own.

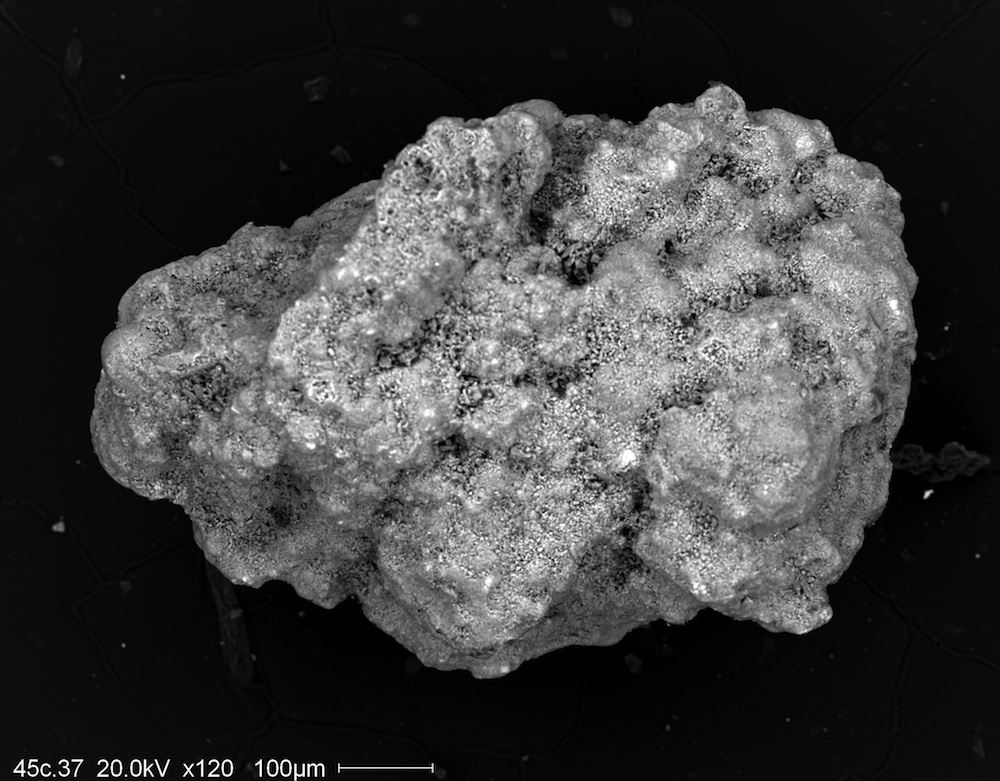

Frank Keppler, a biogeochemist at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, led a study to analyze the Murchison meteorite that landed in Australia in 1969. He reasoned that if he could understand how chloromethanes formed from this meteorite, he might be able to shed some light on whether the ones found on Mars came from Earth, from other meteorites or from the Red Planet itself — and possibly from life.

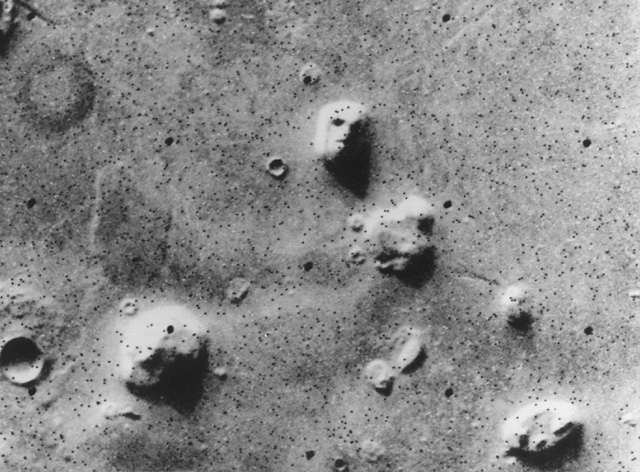

Mars is constantly pummeled by small rocks called micrometeorites. "Every year, about 50,000 tons fall on the Martian surface," Keppler said. Most of these are carbonaceous, meaning they contain carbon, an essential building block for life.

The researchers heated up material from the Murchison meteorite to temperatures of up to 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 Celsius), similar to those in the Viking and Curiosity experiments, and sure enough, they found chloromethane. They knew it wasn't contamination from Earth because it had a different chemical fingerprint.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To determine whether the chloromethane on Mars came from Earth, from meteorites or from the Martian soil, scientists could measure its isotopic signature, Keppler said. At the moment, the landers on Mars (including Curiosity) do not have the tools to measure these isotopes, but perhaps future missions will, he said.

Based on the findings, the presence of chloromethane is a "clear sign" that organic matter exists on Mars, Keppler said. This doesn't necessarily suggest the organic matter came from life, he said, "but we cannot exclude it."

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitterand Google+.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.