Philae Lander On Comet Could Wake Up As It Nears Sun: Scientists

PARIS — Managers of Europe’s Philae comet lander, which went into hibernation Nov. 15 after its battery drained 56 hours after touchdown, on Nov. 18 made a virtue of a necessity in saying Philae's overly shadowed location will be an advantage as Comet 67P approaches the sun in the coming months.

At that point, they said, it is "probable" that the increased doses of solar power will warm the lander, permitting its secondary battery to power up sufficiently to renew communications via the Rosetta spacecraft orbiting overhead.

In response to SpaceNews inquiries, Stephan Ulamec, Philae project manager at the German Aerospace Center, DLR, on Nov. 18 said such a scenario "is very likely to happen. Philae will not overheat on its way to the sun because of its shaded position. Getting closer to the sun means Philae could warm up, wake up and reload its secondary battery by solar power." [Rosetta Mission's Historic Comet Landing: Full Coverage]

As of Nov. 18, Philae managers were still sifting through data from the last communication Philae had with Rosetta early Nov. 15 before its batteries drained.

Early results confirm that the last of Philae's instruments to be switched on, the SD2 Sampling, Drilling and Distribution system, deployed correctly and made an attempt to penetrate the surface ice and collect a soil sample. It remained unclear whether a sample was collected and put into Philae's micro-oven for analysis. There is no evidence either way, DLR said.

"The strength of the ice found under a layer of dust on the landing site is surprisingly high," said Klaus Seidensticker of DLR's Institute of Planetary Research.

Before it went dark, Philae was raised several centimeters and commanded to rotate 35 degrees to optimize its exposure to the sun. DLR said the telemetry from the last data transmission early Nov. 15 confirmed that this maneuver occurred.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Data from Philae's MUPUS instrument, or Multi-Purpose Sensors for Surface and Sub-Surface Science, suggest that while the MUPUS hammer was deployed and its power increased, "we were not able to go deep into the surface," said Tilman Spohn of DLR's Institute of Planetary Research. The instrument nonetheless delivered information on the comet's surface.

The SD2 drill was the last of Philae's instruments to be deployed because ground teams wanted to collect as much data as possible from those instruments whose measurements posed no risk of destabilizing the lander on its precarious perch. Only two of its three legs were securely on the surface.

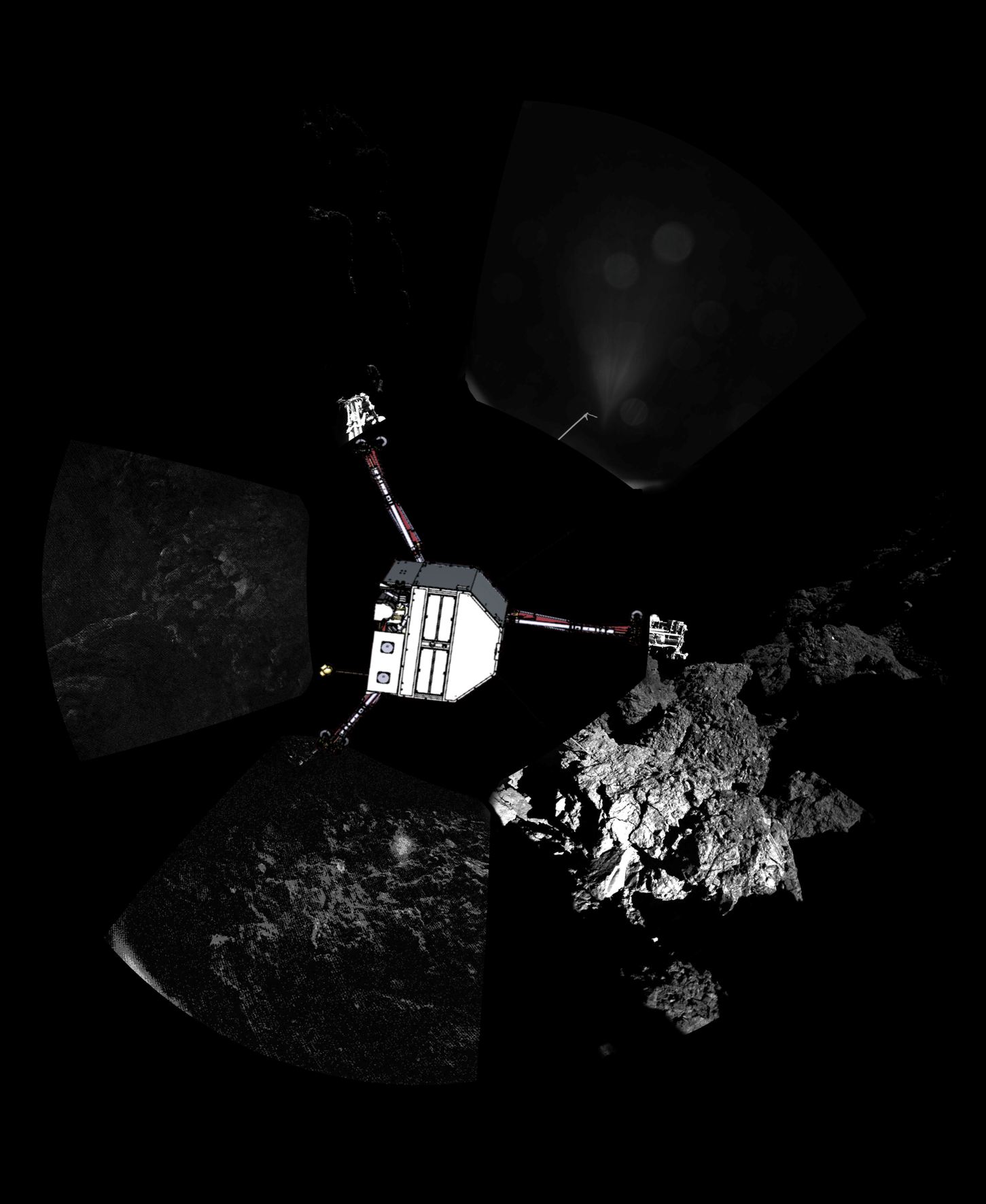

After separating from its mothership, Philae arrived near dead center in its intended landing area on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. But its thruster system, designed to keep it secured on the surface, failed to deploy, as did the harpoons that were to affix it to the surface. Philae thus rebounded off the comet's surface, reaching up to 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) in elevation and travelling for about 1 kilometer over around two hours.

It then touched down and rebounded again, this time for seven minutes, before coming to its final resting place.

Ground teams are still combing through data to determine exactly where Philae is. On Nov. 17, the European Space Agency released a series of photos from Rosetta's Osiris camera showing Philae’s descent. A subsequent photo shows the same area after Philae’s rebound, with small footprints in the dust that were not visible in a previous photo of the spot.

DLR has concluded that Philae worked 56 hours continuously on the surface of the comet, plus the seven-hour descent from Rosetta during which its MUPUS and Rosetta Lander Magnetometer and Plasma Monitor (ROMAP) multisensor experiments both were active. Including the descent, then, Philae logged 63 hours of data.

The only two instruments that were not activated were thermal sensors and accelerometers attached to the harpoon anchoring system.

Philae's exploits 310 million miles (500 million km) from Earth attracted global attention. With the lander now out of the spotlight, at least until its battery is recharged next summer, the Rosetta satellite will continue its unprecedented close-in study of a comet as it approaches the sun. Rosetta is expected to follow the comet for another 18 months or more.

ESA Rosetta managers are debating whether to land Rosetta on Comet 67 at the end of its operational life, but no decision has been made.

This story was provided by Space News, dedicated to covering all aspects of the space industry. Follow them on Twitter @SpaceNews_Inc.

Peter B. de Selding is the co-founder and chief editor of SpaceIntelReport.com, a website dedicated to the latest space industry news and developments that launched in 2017. Prior to founding SpaceIntelReport, Peter spent 26 years as the Paris bureau chief for SpaceNews, an industry publication. At SpaceNews, Peter covered the commercial satellite, launch and international space market. He continues that work at SpaceIntelReport. You can follow Peter's latest project on Twitter at @pbdes.