Mystery Object in Space: A Rogue Black Hole or Strange Supernova?

An object previously thought to be a supernova may actually be a black hole ejected from its home galaxy.

Further observation should provide a definitive answer, but whatever the outcome, the object is unique: If it is a supernova, it's a new breed that radiates for decades, while most supernovas burn out in less than a year. If it's a black hole, it appears to be the product of two black holes that collided, and were simultaneously ejected from their merging parent galaxies.

"This could be a new type of supernova that we've just never seen before. But it would have to be one of the most extreme cases ever observed," said astronomer Michael Koss, who is leading the research. On the other hand, Koss said it could provide all new information about traveling black holes. "Whatever we find, it's exciting." [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

A light where there should be darkness

Koss, a postdoctoral fellow with the Swiss National Science Foundation, started looking at object SN in 2010. Previous observations indicated that SDSS1133 was a supernova, a star that had reached the end of its fuel supply and exploded in a brilliant flash.

But Koss was shocked when he found archival images from the Pan-STARRS telescope going as far back as the 1950s, with SDSS1133 clearly visible in the sky. SDSS1133, whatever it is, has been shining brightly for over 60 years. No known supernova has ever burned for so long. And in the last six months, the object's started getting brighter. Normally supernovas release one brilliant flash and then dim.

Based on recent observations with multiple instruments, including NASA's SWIFT telescope, Koss said a more appealing hypothesis is that SDSS1133 is a black hole. These objects can be surprisingly bright, as the black hole's gravity can heat up nearby gas, which then radiates. These brilliant black holes are also called Active Galactic Nuclei (a family of objects that also includes quasars), because they are typically found at the center of galaxies.

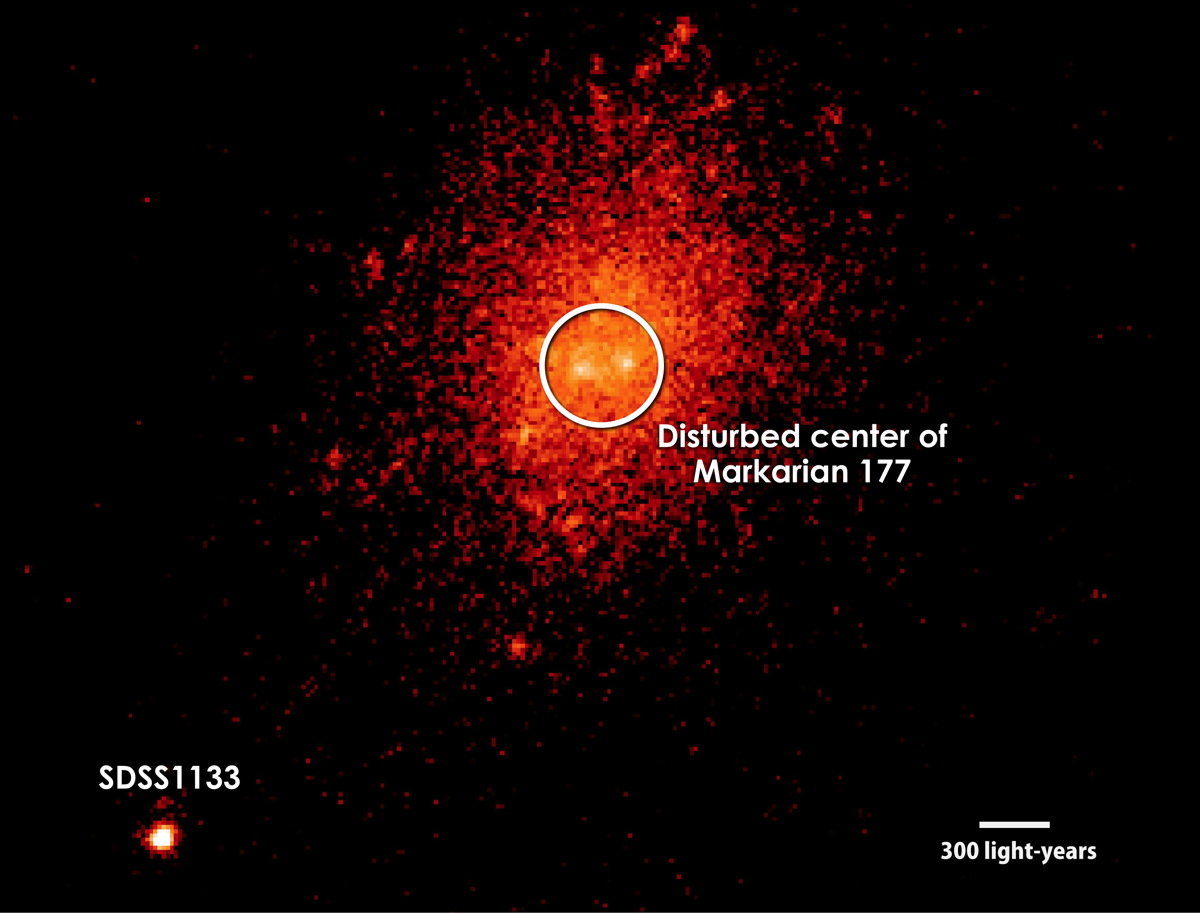

SDSS1133, however, appears to be located 2,600 light-years from its host galaxy's core. Markarian 177 is a dwarf galaxy located in the bowl of the Big Dipper, within the constellation Ursa Major. Observations with the Keck II telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii show evidence that Markarian 177 recently underwent a significant disturbance.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We suspect we're seeing the aftermath of a merger of two small galaxies and their central black holes," co-author Laura Blecha, an Einstein Fellow in the University of Maryland's Department of Astronomy, said in a statement. Blecha studies how two black holes can merge together and experience recoil, a kick that can potentially send the new black hole flying. "Astronomers searching for recoiling black holes have been unable to confirm a detection, so finding even one of these sources would be a major discovery."

The recoil in a black hole merger would come from gravitational waves, which are ripples in space-time, said Koss.

"Colliding black holes are the biggest source of gravitational waves," said Koss. If SDSS1133 is the result of a black hole merger, it would be exciting because that means this type of event can take place in dwarf galaxies, he said. "There are a lot of dwarf galaxies near us. So [merging black holes] might be something we could actually detect."

So what is it?

To figure out if SDSS1133 is a black hole or a supernova, the researchers will look for the presence of a particular type of carbon atom, called carbon 4. The intensity of a black hole merger could create a high volume of carbon 4 in the surrounding material. Koss said the team should be able to observe the abundance of carbon 4 with observations made by the Hubble Space Telescope or the Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

There is one more possibility for SDSS113. If it is neither a black hole nor a new kind of supernova, it could be an unusual type of star called a luminous blue variable (LBV). These massive stars periodically undergo enormous eruptions, spewing large amounts of matter into space. Eventually, they explode as supernovas.

If SDSS1133 is an LBV, then the object would have continually erupted from 1950 to 2001, making it "the longest-[lasting] and most persistent [LBV] ever observed."

Whatever SDSS1133 is, it's something interesting.

The new research was detailed Sept. 19 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter

Most Popular