Philae Lander Sniffed Out Organics in Comet's Atmosphere

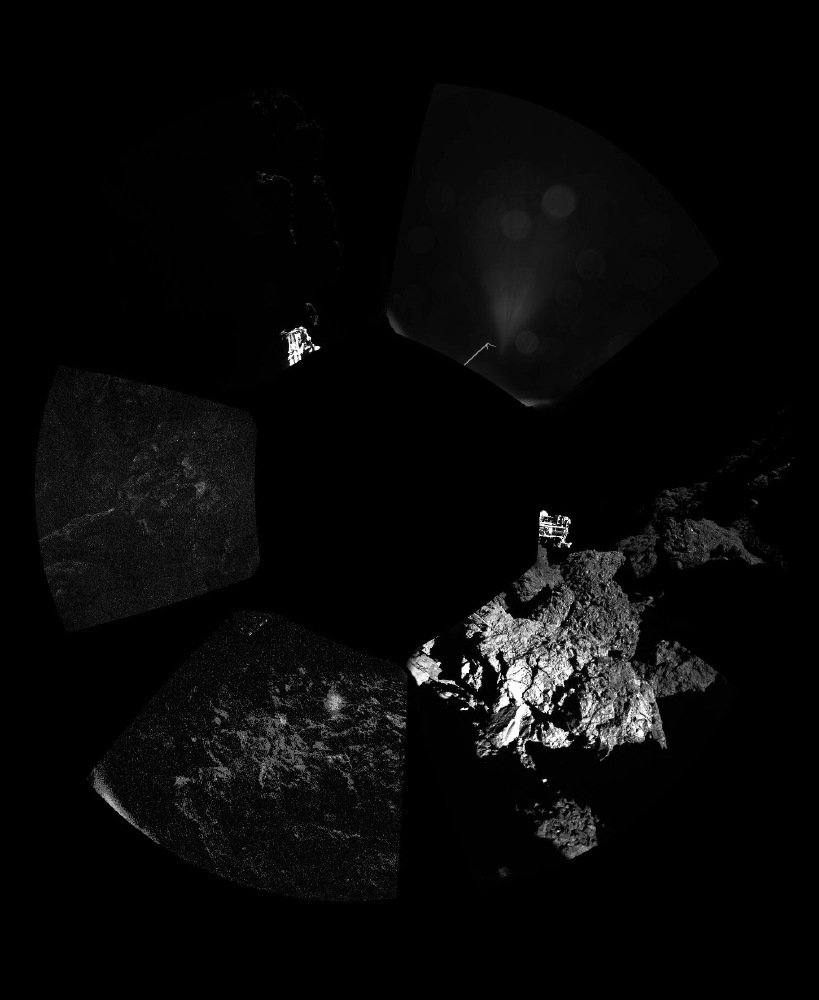

The first probe ever to land on the surface of a comet performed some serious science before going into hibernation. Europe's Philae lander found organic molecules in the comet's atmosphere and discovered that the frigid object's surface is as hard as ice.

On Nov. 12, the European Space Agency's Philae became the first probe to softly land on the face of a comet. After being released from the Rosetta orbiter, the lander actually bounced off Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko twice before coming to its current less-than-ideal resting spot. Because of the low sunlight conditions, Philae went into hibernation after only about 57 hours on the comet when its primary batteries depleted. But the probe still beamed back a wealth of science during its short initial life on the icy body.

While it will take scientists a while to sift through the data collected by Philae, it looks like the probe has sent home some interesting new results. Before shutdown, one of Philae's instruments managed to "sniff" the first organic molecules detected in the atmosphere of the comet, officials with the DLR German Aerospace Center said. However, scientists still aren't sure what kind of organics — carbon-containing molecules that are the building blocks of life on Earth — were found. [See amazing photos from Philae and Rosetta]

Philae also found that Comet 67P/C-G's surface is harder than researchers initially thought it would be. Before the probe's battery ran out, Rosetta mission controllers commanded Philae to hammer into the surface of the comet, and found that the cosmic body is probably as hard as ice, according to ESA.

"Although the power of the hammer was gradually increased, we were not able to go deep into the surface," research team leader Tilman Spohn, of the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, said in a statement. "We have acquired a wealth of data, which we must now analyze."

An instrument onboard Rosetta has also recently made an important discovery for scientists interested in the composition of the comet's ice and its potential implications for how Earth became a watery world.

According to Science Magazine's Eric Hand, the ROSINA instrument (short for Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis) has determined the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio (D-to-H ratio) of water in the comet's atmosphere. The ratio is higher than that found in oceans on Earth, and even higher than in other comets, Hand added, citing ROSINA principal investigator Kathrin Altwegg of the University of Bern in Switzerland. (Deuterium, also known as "heavy hydrogen," contains one proton and one neutron in its nucleus; "normal" hydrogen has one proton and no neutrons.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Three years ago, the comet Hartley-2 was found to have a D-to-H ratio near that of Earth's oceans — sparking interest in the notion that comet impacts delivered much of Earth's water," Hand wrote. "Altwegg says the result for 67P could make asteroids the primary suspect again."

Mission controllers on Earth commanded Philae to drill into the surface of the comet just after it came to rest in its final landing spot, but officials aren't sure exactly how much comet material was collected by the instrument.

"We currently have no information on the quantity and weight of the soil sample," Fred Goesmann, of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, said in a statement.

ESA officials are still hopeful that Philae could get in touch again as Comet 67P/C-G makes its way around the sun. It's possible that the sunlight and temperature conditions around the lander could change as the comet gets closer to our star, allowing Philae to potentially come back to life.

"I'm very confident that Philae will resume contact with us and that we will be able to operate the instruments again," DLR lander project manager Stephan Ulamec said in a statement.

Rosetta is expected to stay with the comet as it makes its closest approach to the sun in August 2015. The orbiter is scheduled to study the spacecraft through at least December 2015.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.