A Christmas Comet to be Seen From Dark Skies

This article was originally published on The Conversation. The publication contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

If you are away from the bustle of the city these holidays, then try your luck at spotting a faint comet in the northern sky.

Comet Lovejoy C/2014 Q2 is the fifth comet to be discovered by Brisbane amateur astronomer Terry Lovejoy. Comets are the only astronomical objects that are automatically named for the person who found them.

Lovejoy found the comet last August using an 8-inch telescope. It was about the same distance from the sun as the asteroid belt and was located around 420 million km from Earth. At that distance, the comet’s brightness was measured at 15th magnitude, which is about 4,000 times fainter than the eye can see.

However, in the last few months Comet Lovejoy has been moving closer and it is now about 100 million km away. Amateur astronomers have been watching its approach using telescopes and binoculars. And in the last few days it has become just bright enough to be seen with the naked eye.

Faint comet, dark skies

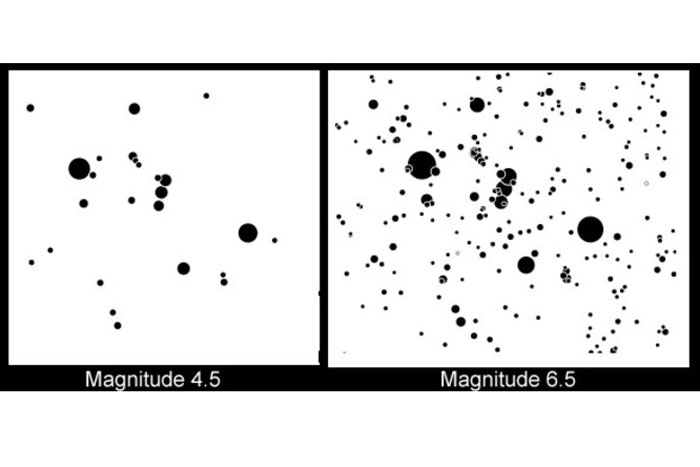

The comet seems to be brightening a little faster than expected and its brightness should continue to increase slightly as it travels by Earth. Even so, it’s always going to be a tough one to spot and you’ll need lovely dark skies away from any suburban lights to have a chance to see it without the help of binoculars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Comets are inherently unpredictable and it’s always hard to know exactly how bright they might become as they head towards the sun. The closest this comet will get to the sun is around 93 million km on January 30 (that’s about 15 million km closer than Venus).

It’s also not the first time that the comet has passed through the inner solar system. It has a period of the order of 10,000 years and spends most of that time heading out to the Oort Cloud. This a sphere of icy comets that extends from a few 100 billion to trillions of kilometres from the sun.

While we may have to watch the comet closely to see how it’s brightness changes, it is possible to map out its orbit very precisely.

Across the northern sky

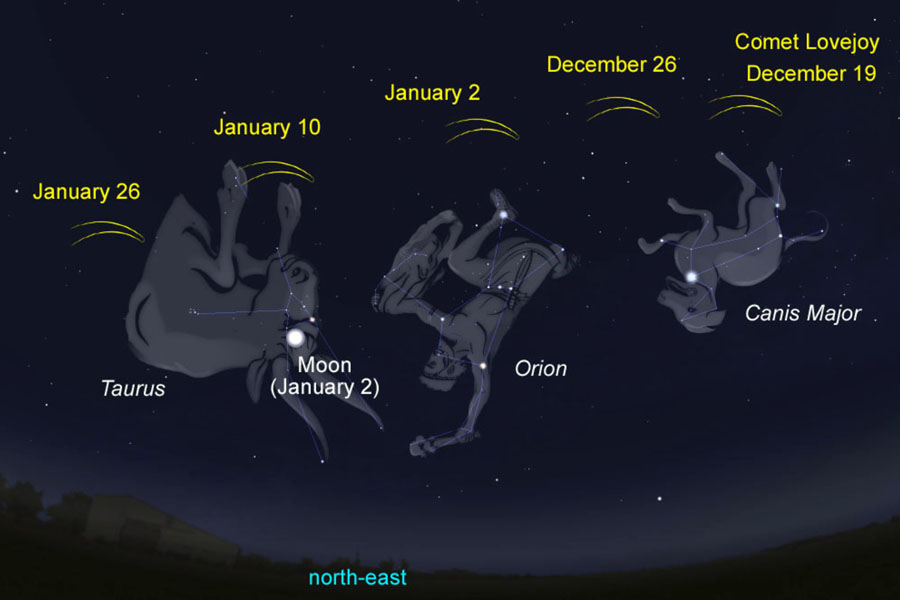

What’s great about Comet Lovejoy’s path is that it passes above some of the best constellations in the summer sky. It will appear above Canis Major throughout December, then move past Orion during early January and by late January it appears above the constellation of Taurus.

These constellations can be found in the northern sky throughout the entire night across Australia. Although with the comet being so faint it’s best to start observing around two hours after sunset, when the sky is nice and dark.

The comet will make its closest approach to Earth on January 7, at a distance of about 75 million km. It’ll be interesting to see how much the comet brightens from now until December 25.

After that, the moon will start appearing in the northern sky, making it harder to see the comet. Two weeks later, from January 9, there will be an hour or so of dark sky to catch the comet before the moon rises.

That week, from January 9-16, should be a good time to view the comet because even though it will be moving away from Earth it will still be heading towards the sun. This means its intrinsic brightness should continue to rise. It’s currently estimated that the comet will peak in apparent brightness at a magnitude of 4.4 on January 10.

By the last week of January, the comet will have moved too far north to be seen from Australia. During February, it’ll travel between Andromeda and Perseus, two prominent constellations for the northern hemisphere.

You can find out where to see the comet from your specific location and get up-to-date information regarding its expected brightness at the website In-The-Sky.org maintained by British astronomer Domenic Ford.

A comet’s green glow

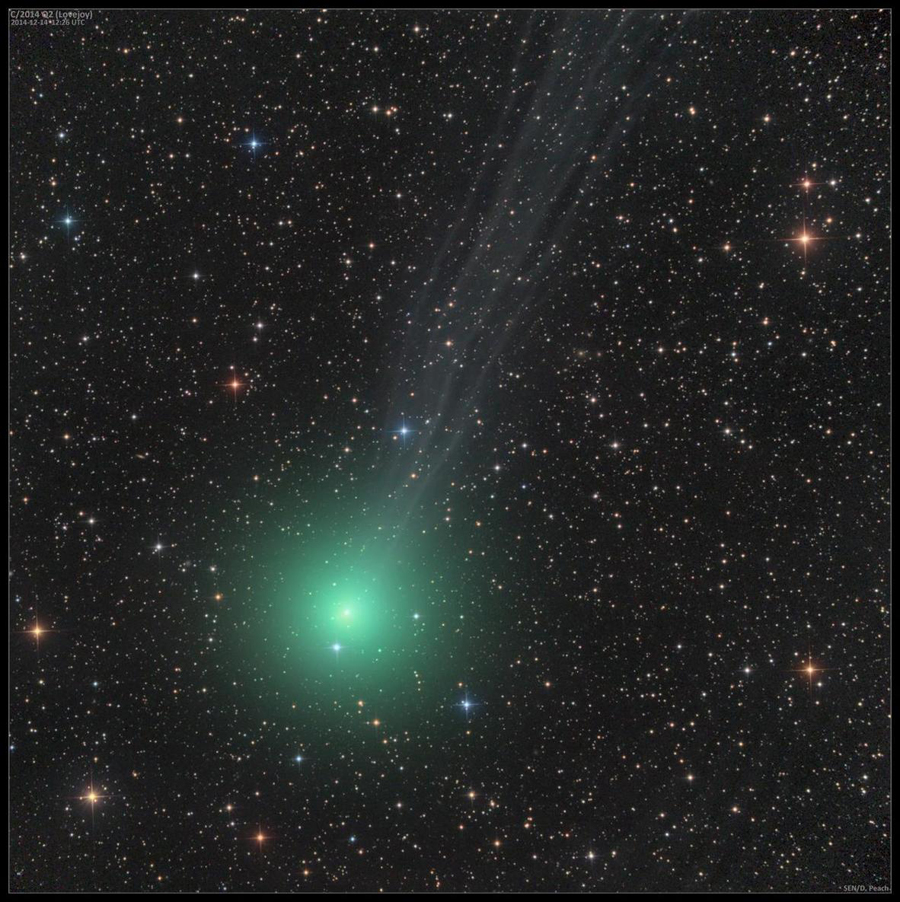

Comet Lovejoy is faint to see with the naked eye, but astrophotographers are already getting some great shots of the comet. One thing that’s easily noticed is the comet’s bright green colour.

The colour is likely due to the presence of two gases – cyanogen (CN)2 and diatomic carbon (C2) – which glow green when their molecules are ionised or excited. Ionisation causes electrons within the molecules to gain energy and when the electrons drop back down to their normal state, they give off light of a certain wavelength. For these molecules they emit green light and since they are very strong emitters, their green colour dominates the comet.

Christmas comets

This is the third comet of Lovejoy’s to be visible around Christmas time. Last year, Comet Lovejoy C/2013 R1 could be seen faintly from the northern hemisphere throughout November and December.

While back in 2011, Comet Lovejoy C/2011 W3 was a lovely comet for Australian skies with an impressive tail. This comet was a sun grazer, and it passed just 140,000km above the surface of the sun on December 16, 2011.

The current Comet Lovejoy may only be seen as a faint fuzzy blob in the night, but it’s in such a rich and interesting part of the sky and it won’t be around again for another 8,000 years, so why not take some time out to enjoy the evening sky this Christmas.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

I am an extragalactic astronomer, Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne, and am currently working in the field of science communication at Melbourne Planetarium.

I have been the Curator (Astronomy) at Melbourne Planetarium, Scienceworks since 1999, drawing on my background in research astronomy to create more than a dozen planetarium productions. The most recent of these are now screened in over fifty planetariums across sixteen countries world-wide.

I am proud to be the Australian Representative of the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Science Outreach Network. This sees me working with Astronomy Australia Limited (AAL) to promote ESO’s extensive research accomplishments throughout Australia.

I am also involved in projects to bring research astronomy data into the planetarium to both engage the public and to turn the planetarium into a tool for research astronomers wanting to know more from their data.