This past year was a banner one for the field of exoplanet science, with the tally of known alien worlds doubling to nearly 2,000 by the end of 2014.

Here's a look at the top exoplanet discoveries of 2014, from the first potentially habitable Earth-size world to a staggering haul of 715 newly announced alien planets:

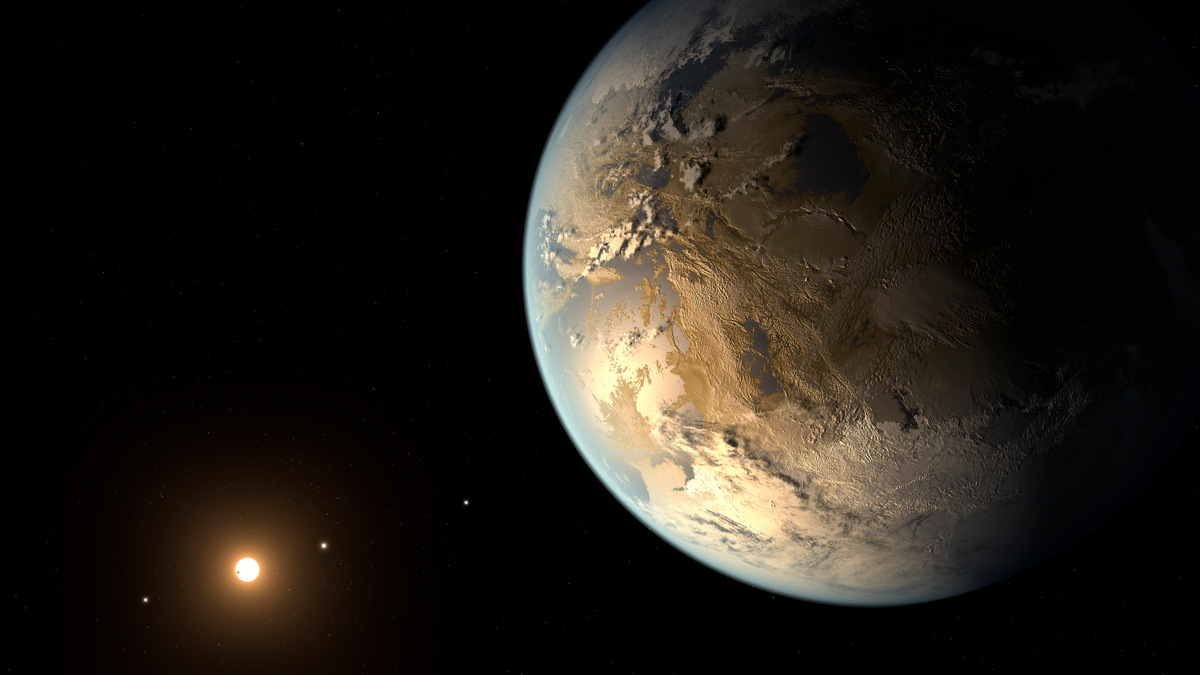

'Earth's cousin'

In April, scientists announced the discovery of Kepler-186f, the first known Earth-size planet that resides in its star's "habitable zone" — the range of distances that could support the existence of liquid water on a world's surface. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

As its name suggests, Kepler-186f was found by NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope. The planet lies 490 light-years from Earth and is just 10 percent wider than our home world. Kepler-186f is not the elusive "Earth twin" that astronomers have long sought; the planet circles a red dwarf, a star smaller and dimmer than the sun. But Kepler-186f is a member of the family nonetheless, with its discoverers characterizing it as an "Earth cousin."

A habitable world next door?

Kepler-186f isn't the only planet found last year that might be capable of supporting life. A world called Gliese 832c is also potentially habitable — and it lies just 16 light-years away, a mere stone's throw considering the vast scale of the universe.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers found Gliese 832c, which also orbits a red dwarf, using three different ground-based instruments. The exoplanet is a "super Earth" at least five times as massive as Earth, its discoverers say. While Gliese 832c may be habitable, it could also resemble scorching-hot Venus, whose thick atmosphere has led to a runaway greenhouse effect.

715 newfound exoplanets

Exoplanet discoveries usually come in drips and drops, but in February, the Kepler team unleashed a torrent: Researchers announced the spacecraft had spotted 715 new alien worlds, nearly doubling the known population in one fell swoop.

More than 90 percent of the newfound planets are smaller than Neptune, and four of them are habitable-zone worlds less than 2.5 times the size of Earth, scientists said.

Researchers confirmed this huge haul of Kepler planets using a technique called "validation by multiplicity," which relies on probability and statistics rather than additional observations by other telescopes.

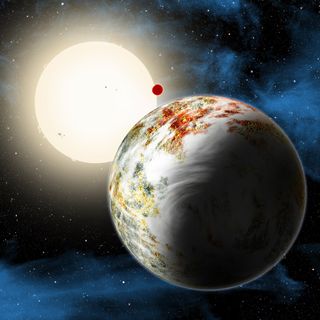

'The Godzilla of Earths'

Another headliner from 2014 is Kepler-10c, a planet about 17 times more massive than Earth. Such hefty worlds were thought to be primarily gaseous, but Kepler-10c is rocky.

Kepler-10c is therefore the first known member of a new class of exoplanets, the "mega-Earths." This "Godzilla of Earths," as one of its discoverers described Kepler-10c, orbits a sunlike star that lies about 560 light-years from Earth.

Gas dwarfs

Just as rocky planets can apparently be much larger than previously thought, gaseous worlds can be surprisingly small. That's the conclusion of another 2014 study, which laid out the classification of "gas dwarf" exoplanets. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

After studying more than 600 newfound Kepler planets, the researchers determined that worlds less than 1.7 times the size of Earth are likely to be rocky, while those at least 3.9 times bigger than our planet are gaseous. Most worlds between these two extremes are probably "gas dwarfs," planets with rocky cores and thick hydrogen-helium atmospheres that never grew to the size of Saturn, Jupiter and other gas giants, the study found.

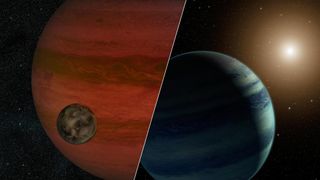

The first exomoon?

Astronomers may have detected the moon of an alien planet for the first time in 2014, but we'll never know for sure.

The team used a technique called gravitational microlensing, which notes how a foreground object's gravity warps the light from a distant star when it passes in front of the star from Earth's perspective. The researchers saw one lensing event caused by a foreground object that could be one of two things: a free-flying "rogue planet" with a rocky exomoon, or a small star that hosts a planet about 18 times more massive than Earth.

Unfortunately, there's no way to follow up on the find, because microlensing events are random encounters. So the search for the first confirmed exomoon continues.

The first exoplanet of Kepler's new mission

Kepler's original exoplanet hunt ground to a halt in May 2013, when the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed. But the Kepler team devised a way to stabilize the observatory using sunlight pressure, and in May 2014, NASA approved a new, two-year mission for the spacecraft called K2, during which it has been hunting for alien planets, supernova explosions and other cosmic phenomena. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

The first K2 exoplanet is now in the books. In December, researchers announced that Kepler had discovered a world called HIP 116454b, which is about 2.5 times bigger than Earth and lies 160 light-years away.

However successful K2 turns out to be, the new mission won't approach the exoplanet tally Kepler racked up during its pre-glitch operations. Kepler's original mission netted nearly 4,200 planet candidates, nearly 1,000 of which have been confirmed to date. Kepler scientists expect about 90 percent of the candidates will turn out to be bona fide planets.

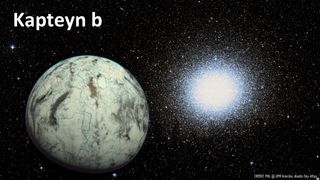

The oldest potentially habitable alien planet

Also this year, astronomers announced the discovery of Kapteyn b, a super Earth that orbits in the habitable zone of a red dwarf located just 13 light-years away from our solar system.

Kapteyn b is 11.5 billion years old, making it the most ancient known planet that may be capable of supporting life. To put that age into perspective: Earth is less than 4.6 billion years old, while the universe itself was born 13.8 billion years ago. So if life took root early in Kapteyn b's history, it has had a very long time to evolve.

Planets around every star?

Another 2014 study suggests that virtually every red dwarf in the Milky Way galaxy hosts at least one planet — and that at least 25 percent of these small, dim stars in the sun's own neighborhood host habitable-zone worlds.

That translates to a lot of life-friendly real estate; red dwarfs make up at least 70 percent of the galaxy's 100 billion or so stars.

The team arrived at these conclusions after analyzing observations made by two instruments in Chile — the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) and the Ultraviolet and Visual Echelle Spectrograph (UVES). The results bolster previous findings made by researchers who looked at Kepler data, indicating that the Milky Way is teeming with billions of planets.

Earth-like worlds in two-star systems?

This year, for the first time, astronomers found a rocky planet in an Earth-like orbit around a single star in a two-star system.

The world, known as OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb, lies about 3,000 light-years from Earth and is likely too cold to support life as we know it (it circles a red dwarf). And it's not the first planet to be spotted in a two-star system, or the first one known to circle just one of a binary's two stars.

But the discovery of OGLE-2013-BLG-0341LBb is significant, showing that rocky planets can form relatively far from their host stars even in two-star systems, researchers said. (Previously, it was thought that a nearby companion star might disrupt the planet-forming disk too much for this to occur.) Its existence suggests that habitable planets may be more common than scientists had supposed; half of all Milky Way stars exist in binary systems.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.