'Dark Nebula' Hides Hundreds of Baby Stars (Photo, Video)

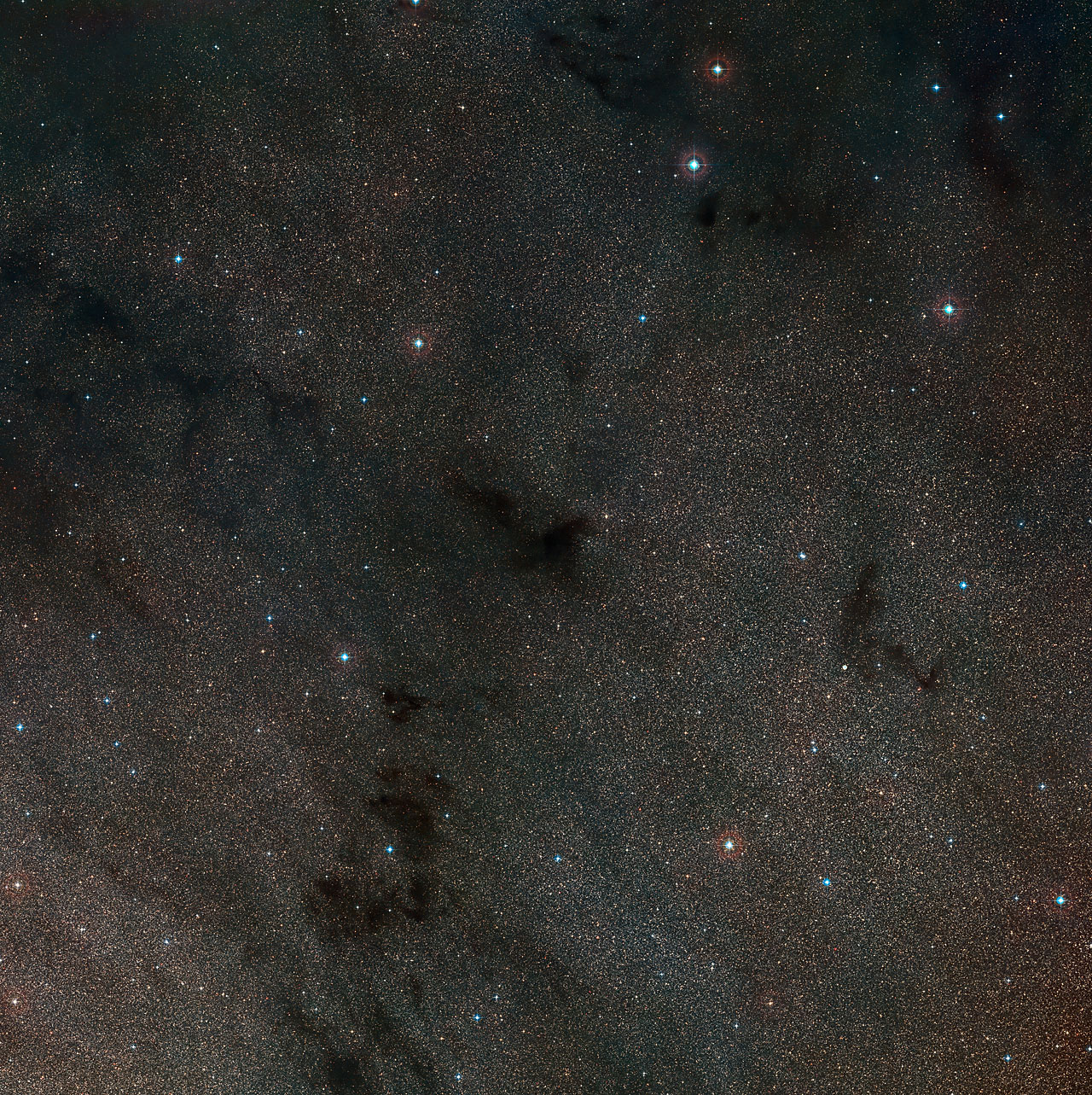

A "dark nebula" of thick space dust blots out the light from a teeming star nursery in a striking new imag from an observatory in Chile.

The new view of the Lynds Dark Nebula 483, or LDN 483, shows off a region of starbirth that includes wide swaths that are obscured in visible light. It was obtained using the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at La Silla Observatory, which is overseen by the European Southern Observatory.

In the new image, the molecular dust clouds inside LDN 483 are so thick that they obscure light from the stars behind the clouds. While the disappearing act makes it appear at first glance that stars cannot be born here, the thick ooze of materials indicates quite the opposite. [Photos: Strange Nebula Shapes]

"Astronomers studying star formation in LDN 483 have discovered some of the youngest observable kinds of baby stars buried in LDN 483's shrouded interior," ESO officials wrote in a statement. "These gestating stars can be thought of as still being in the womb, having not yet been born as complete, albeit immature, stars."

LDN 483 is located about 700 light-years from Earth in the constellation Serpens, the Serpent.

As a star evolves, the force of gravity slowly contracts a ball of dust and gas that is pulled from the surroundings. The stellar youngster isn't producing much heat yet — its temperature is only at about minus 418 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 250 degrees Celsius).

Eventually, as the baby star's core contracts, pressure and temperature will increase and fusion will ignite. But before it reaches that point, the protostar will spend a blink of astronomical time — about a few thousand years — in the earliest stage, and then a few more million years getting warmer, denser and putting out increased-energy light emissions. As time goes on, it will shine in visible light rather than just in infrared.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"As more and more stars emerge from the inky depths of LDN 483, the dark nebula will disperse further and lose its opacity," ESO officials wrote. "The missing background stars that are currently hidden will then come into view — but only after the passage of millions of years, and they will be outshone by the bright young-born stars in the cloud."

The term Lynds Dark Nebula is rooted in the American astronomer Beverly Turner Lynds, who compiled and published a survey of dark nebulas— the Lynds Dark Nebula catalogue — in 1960. At that time, Lynds discovered dark nebulas through the painstaking visual inspection of photographic plates of observations made by the Palomar Sky Survey.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.