Milky Way's Monster Black Hole Unleashes Record-Breaking X-ray Flare

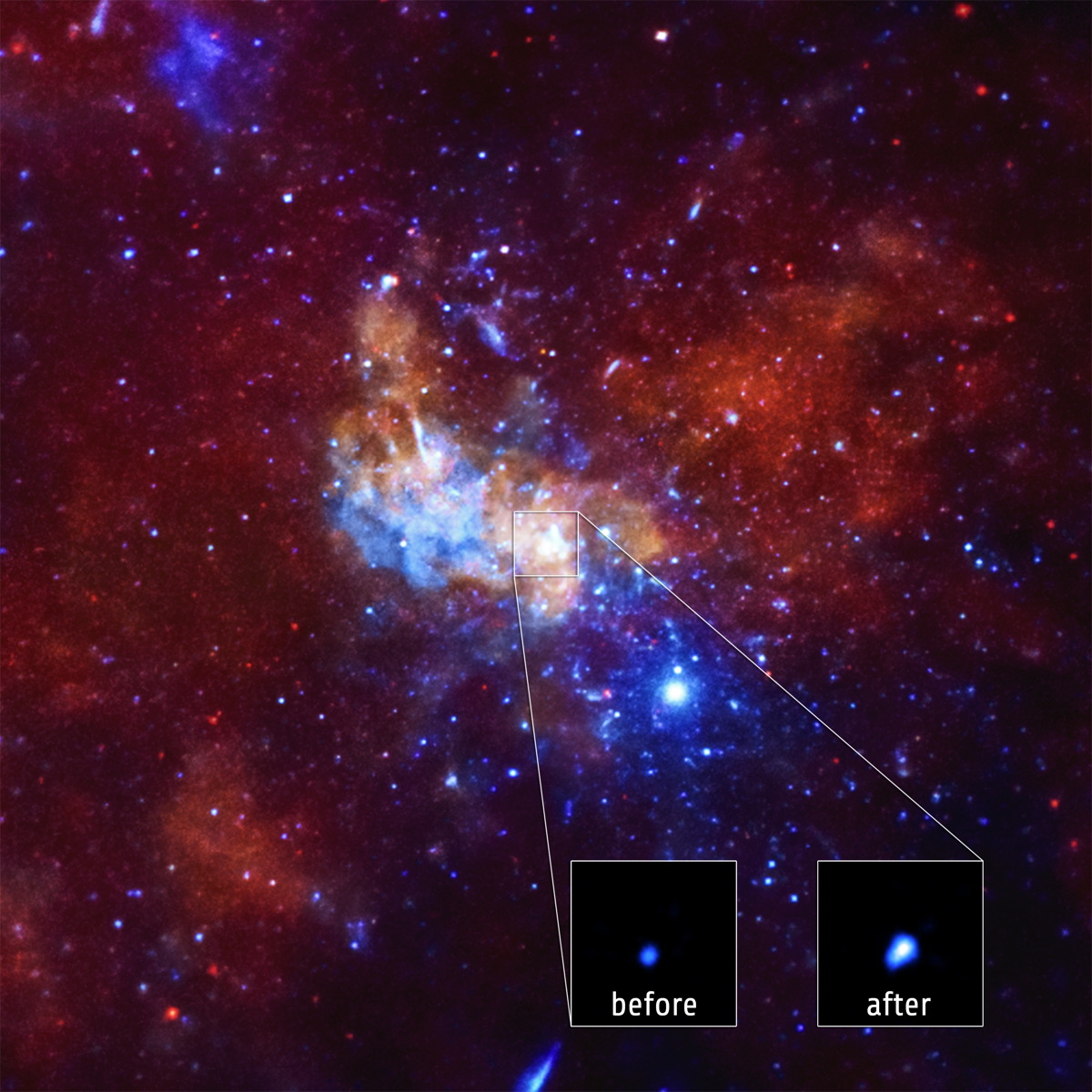

SEATTLE —The giant black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy recently spit out the largest X-ray flare ever seen in that region, astronomers say.

The enormous eruption from the Milky Way's core was detetected on Sept. 14, 2013, very close to the supermassive black hole known as Sagittarius A*. Pronounced "Sagittarius A star" and abbreviated as Sgr A*, the Milky Way's monster black hole has a mass that is about 4.5 million times that of the sun. Scientists unveiled the discovery of the record-breaking flare this month at the 225th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

The so-called "megaflare" flare was spotted by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, which can peer through dust and starlight to the center of the Milky Way. The event was 400 times brighter than the normal level of radiation from this region and nearly three times brighter than the previous record-holding flare, recorded in 2012. A second X-ray flare, with a flash 200 times brighter than normal levels, was then seen on Oct. 22, 2014. [No Escape: Black Holes Explained (Infographic)]

Daryl Haggard, of Amherst College in Massachusetts, presented the findings at a news conference here at the AAS meeting on Jan. 5. Haggard and her colleagues have two possible explanations for what might have caused the flare. First, the black hole may be behaving like our own sun, which also emits bright X-ray flares. In the sun, these flares occur when magnetic-field lines become very tightly packed together or twisted, and the researchers said it's possible something similar took place near the black hole.

It's also plausible that the flare was the product of Sgr A* having a snack. An asteroid or other object may have come too close to the black hole, ripping it apart. The debris would have accelerated rapidly and potentially radiated a bright burst of X-rays.

"If an asteroid was torn apart, it would go around the black hole for a couple of hours — like water circling an open drain — before falling in," Fred Baganoff, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a member of the research team, said in a statement. "That's just how long we saw the brightest X-ray flare last, so that is an intriguing clue for us to consider."

Researchers saw the flare by chance while watching Sgr A* in anticipation of a different event: A gas cloud called G2 was set to make a close pass by Sgr A*, and some scientists hypothesized that material from G2 would fall into the black hole, generating a bright display of X-rays, NASA officials said in a statement. But no X-ray signal was detected as G2 made its closest approach to Sgr A*. The new flares do not appear to be part of the missing light show, according to Haggard.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This time scale is characteristic of an object roughly one astronomical unit (the distance from the Earth to the sun) from Sgr A*, Haggard added. G2's closest approach to Sgr A* was 150 astronomical units, "so the time scale doesn't quite match up," she added.

Haggard and her colleagues are hoping for flares from Sgr A*. With more detailed observations, she said, it might be possible to discern whether Sgr A* is rotating or stationary — a feature that can change aspects of a black hole's physiology.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter