Ten years ago today (Jan. 14), humanity got its first up-close look at a bizarre, frigid moon that may be capable of supporting life as we know it.

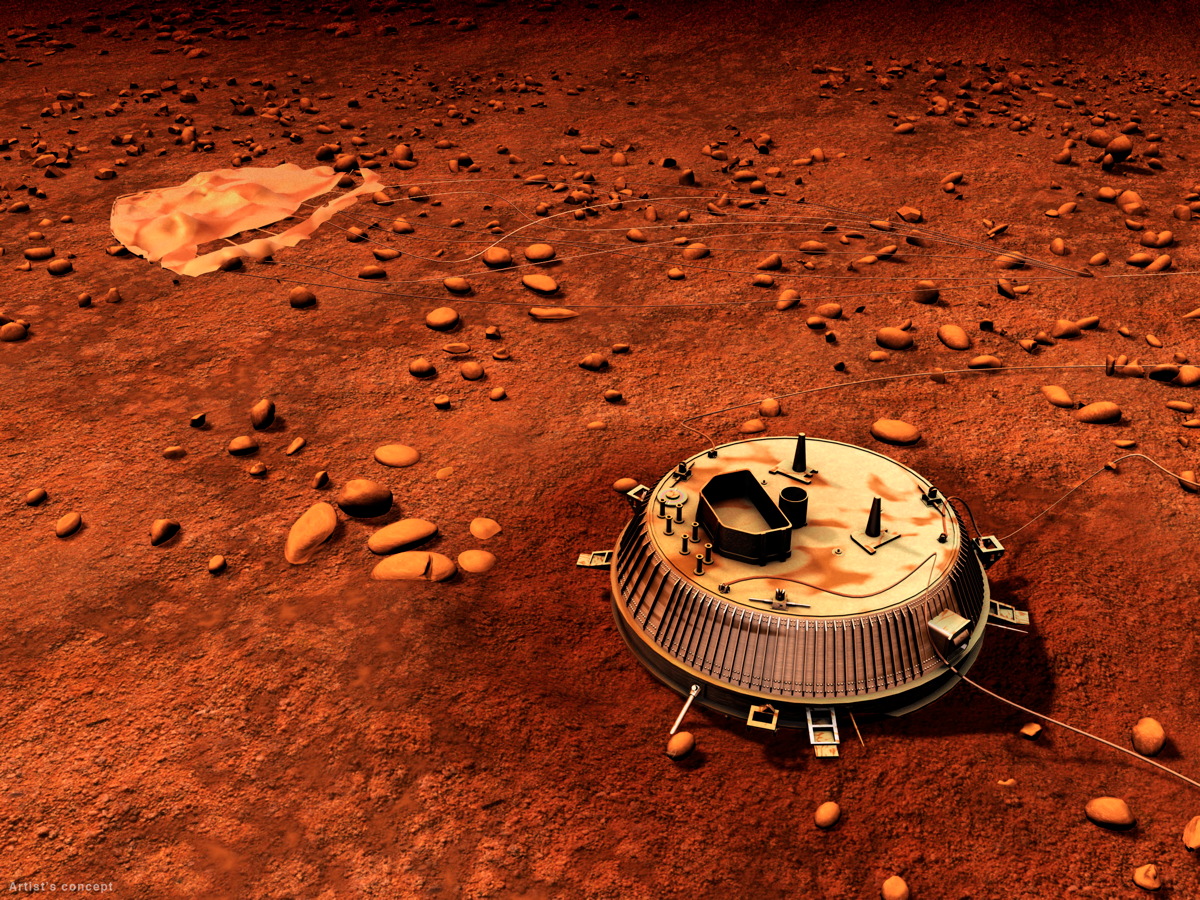

The European Space Agency's (ESA) Huygens probe touched down on the surface of Saturn's huge moon Titan on Jan. 14, 2005, three weeks after being deployed from its mothership, NASA's Cassini spacecraft. For the first time ever, an emissary from Earth had landed softly on a world in the outer solar system.

"I distinctly recall the dreamy feeling of being in one universe one moment and in another universe the next," Cassini imaging team leader Carolyn Porco wrote of Huygens' landing in a blog post today. "But it was no dream. We had, without doubt, journeyed to Titan, 10 times farther from the sun than the Earth, and touched it. The solar system suddenly seemed a very much smaller place." [What Huygens Saw on Titan (Video)]

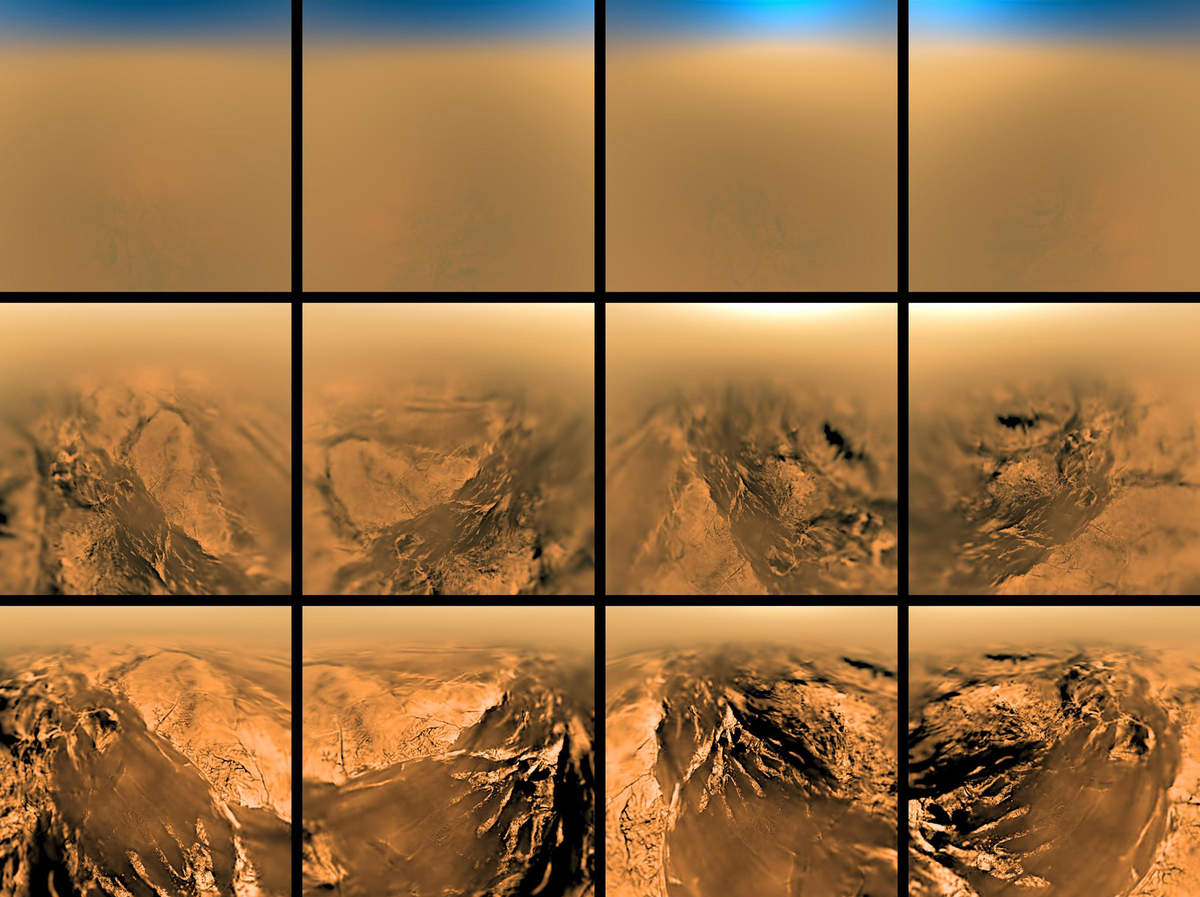

Cassini reached the Saturn system in July 2004 and thus had already observed Titan by the time Huygens touched down. But the lander beamed home information impossible to obtain from afar, a data haul that began during Huygens' two-and-a-half-hour descent through the moon's thick atmosphere.

"The images taken by the falling probe and released to the public that night were everything our images from orbit were not: unfiltered, exquisitely detailed views of the moon's surface and unambiguous in their account," Porco wrote.

Those images revealed what appeared to be a shoreline, as well as snaking channels that had obviously been carved by flowing liquid, she added. But that liquid was not water; Titan has a hydrocarbon-based weather system.

"It was circumstantial but incontrovertible evidence for the liquid hydrocarbons that we had strained from orbit to find, and thrilling beyond measure," Porco wrote. "It was soon to be followed, after landing, by another unforgettable sight, under a cloudy sky and across a cobble-strewn ground to the moon's horizon in the distance."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Huygens kept sending data to Earth from Titan's freezing surface for 72 minutes before its batteries died and the probe went dark.

The lander's measurements and observations helped lift the veil of mystery that had enshrouded Titan. For example, Huygens took a detailed profile of Titan's nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, gathering temperature, pressure and density readings over a wide range of altitudes.

Furthermore, Huygens' analyses of Titan's atmospheric methane did not support the suggestion that the gas was produced by microbes, ESA officials said. (Most of the methane found in Earth's atmosphere has a biological origin.)

You can read more about Huygens' discoveries here, in a top 10 list ESA compiled to commemorate today's anniversary.

While Huygens ceased operations shortly after touching down on Titan, Cassini has continued to study the huge moon (along with Saturn itself, and many of its other moons). For example, over the course of more than 100 flybys, Cassini has mapped much of Titan's surface and, using radar, probed the depth of some of the moon's biggest hydrocarbon seas. Moreover, gravity measurements by Cassini suggest that Titan harbors a subsurface ocean of liquid water, NASA officials said.

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort of NASA, ESA and the Italian Space Agency — launched in 1997. The Cassini spacecraft is scheduled to keep making observations through September 2017, when the orbiter will end its life with an intentional death dive into the ringed planet's thick atmosphere.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.