See 3 Moons of Jupiter Perform Rare Triple Transit Friday Night

On Friday night (Jan. 23), observers all across North America will witness a rare event when three of Jupiter's moons, and their shadows, pass across the face of the giant planet.

How rare are these Jupiter triple transits? I have seen two in the last 15 years personally, but the next one will not occur until 2032.

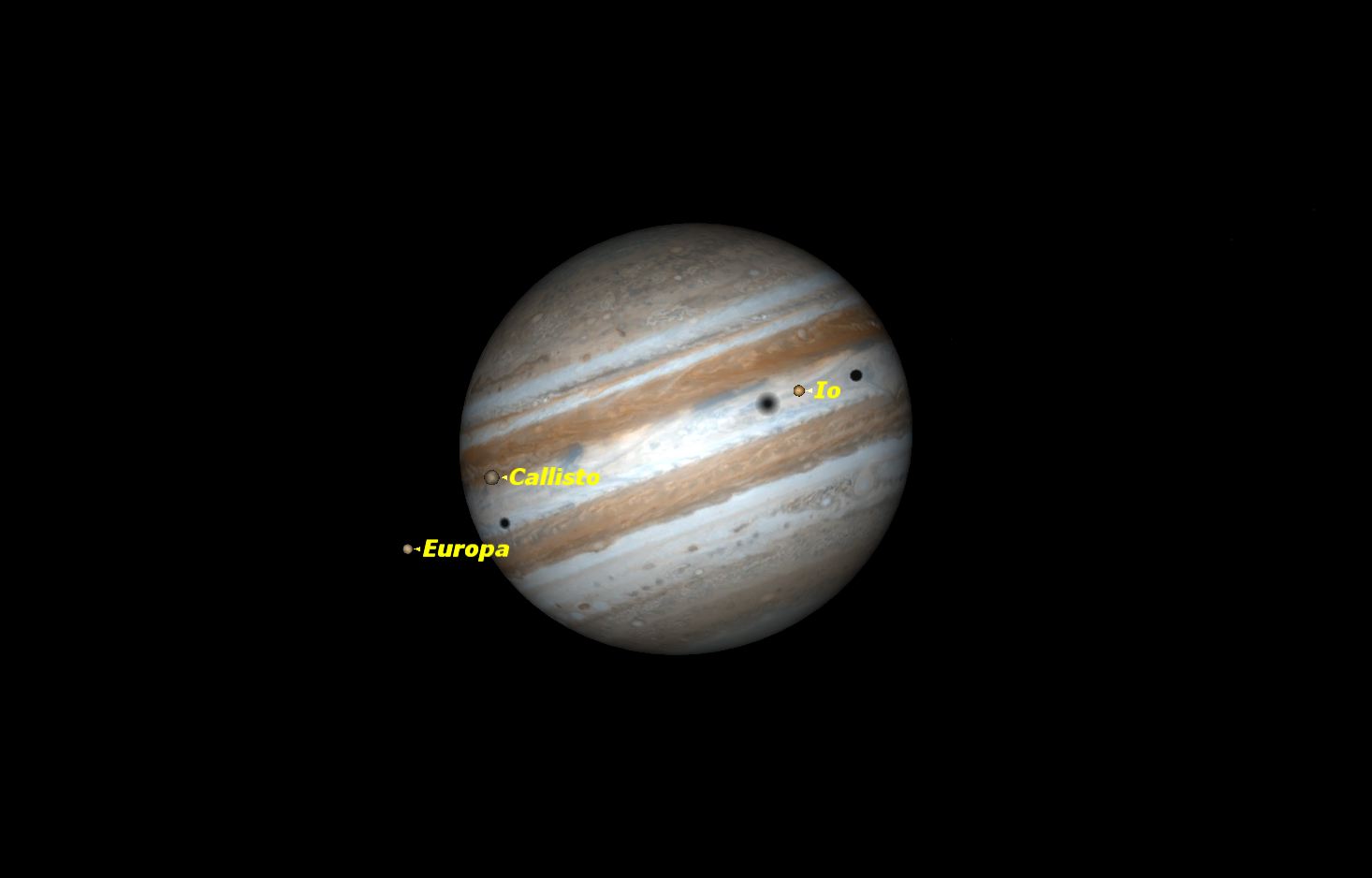

As Galileo found early in the 17th century, Jupiter has four large, bright moons that are usually seen as points of light on one side of the planet or the other. These satellites — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — are known as the Galilean moons, after their discoverer. Jupiter has at least 63 smaller moons, most of which are too small to be seen with amateur telescopes. [Photos: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter]

As the Galilean moons revolve around the giant planet, they sometimes pass in front of it and sometimes are lost in its shadow or behind the planet itself. In addition, all four moons cast their own shadows on Jupiter's cloud tops.

Because of the complex gravitational interaction between Jupiter and its moons, their motions are not independent, but are locked in specific patterns. The orbital periods of the three inner moons are as follows: Io, 1.769 days; Europa, 3.551 days; Ganymede, 7.155 days.

If you divide these periods by Io's period, you find that they are almost perfectly in the ratio of 1:2:4, a classic example of orbital resonance. Only Callisto doesn't fit the pattern, with an orbital period of 16.689 days.

Because of this resonance, Io and Europa frequently cross the face of Jupiter at the same time, but Ganymede is always far away when this happens.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The inky black shadows of the moons can be seen, under steady seeing conditions, with a 90mm aperture telescope. The shadows are very small, but very high-contrast. The moons themselves are more challenging. I have seen Ganymede and Callisto with a 127mm aperture, but Io and Europa are hard to see with my 280mm aperture, except just as they enter or leave Jupiter's disk. Io and Europa simply blend in with the cloudy surface of the planet.

Here is a rundown of the events Friday night and Saturday morning (Jan. 24), given in EST. If you live in western parts of North America, subtract 1 hour for CST, 2 hours for MST, or 3 hours for PST.

10:11 p.m.Callisto's shadow enters disk

11:35 p.m. Io's shadow enters disk

11:55 p.m. Io enters disk

1:19 a.m. Callisto enters disk

1:28 a.m. Europa's shadow enters disk, triple shadow transit begins

1:52 a.m. Io's shadow leaves disk, triple shadow transit ends

2:08 a.m. Europa enters disk, triple satellite transit begins

2:12 a.m. Io leaves disk, triple satellite transit ends

3:00 a.m. Callisto's shadow leaves disk

4:22 a.m. Europa's shadow leaves disk

5:02 a.m. Europa leaves disk

6:02 a.m. Callisto leaves disk

Notice that the different moons are in front of Jupiter for different periods because of the differences in their orbital speeds. The shadows are at different distances from the moons themselves because of their different distances from the planet. As a result, the triple shadow transit lasts 24 minutes, from 1:28 to 1:52 a.m. EST, but the triple satellite transit lasts only 4 minutes, from 2:08 to 2:12 a.m. EST.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing photo of Jupiter or any other celestial object that you'd like to sharefor a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.