Moon Crash Stirs Up Ideas For The Future

In a flash it was over.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) SMART-1 spacecraft punched into the Moon's barren surface early Sunday morning. It made an on-purpose plunge and is believed to have slammed into a hillside within the Lake of Excellence, a volcanic plain.

It was a destructive ending to a nearly three-year mission of testing space technology and examining Earth's celestial neighbor. The craft's demise is providing valuable insight into future lunar research.

The exact impact time of SMART-1 was recorded at 1:42:22 a.m. ET on Sept. 3, when ESA's New Norcia ground station in Australia abruptly lost radio contact with the probe.

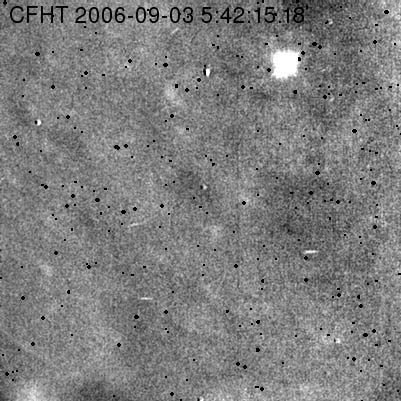

A global network of professional and amateur ground observers focused their respective instruments on the SMART-1's predicted impact zone. So far, at the top of the hit list is the observation by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) from atop Mauna Kea situated on the Big Island of Hawaii.

Scientists at CFHT recorded an impact burst, possibly caused by thermal emission from the roughly 4,500 miles per hour (2 kilometers per second) crash of the spacecraft itself, or maybe the detonation of leftover hydrazine fuel onboard SMART-1.

Dash for the flash

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The impacting spacecraft was caught by WIRCam - a wide-field infrared camera at the CFHT that represents one of the largest astronomical mosaic of infrared detectors ever built.

But readying the WIRCam to track the Moon, as well as handle SMART-1 duties, was no small effort. A bit of luck was needed, too. It was a literal dash for the flash, explained Christian Veillet, Executive Director of the CFHT.

"We moved to WIRCam only on Friday evening, not for SMART-1, but because it is part of our operations," Veillet explained. Time was spent that night to check the camera, the pointing, the filter to be used, he said.

"We had never looked at the Moon with WIRCam," Veillet told SPACE.com. "Our brand new field infrared mosaic looks more into deep space than to nearby bodies."

Veillet said he and his team had no choice but to use the narrowest filter they had for the camera. Also, they had to use exposure times meant more for observing brown dwarfs or remote galaxies, not for up close and personal Moon watching.

Most of Saturday, Veillet said, was busily spent writing scripts to allow the production of decent images in near real time.

"Then came the evening [of the impact]. Weather was superb, everything worked well and we were lucky enough to capture a flash. Actually, I did not think we would see it," Veillet said. He was anticipating that kicked-up dust might be visible after the impact itself.

Right hemisphere at the right time

Due to the camera's operating mode, there was a 30-percent chance of simply missing the event by not looking at the right time.

"The impact happened six seconds after the start of an exposure and four seconds before its end. We saw the flash as soon as the image was processed," Veillet added. The flash looked extremely bright ... much brighter than had been anticipated, he said.

"Finding the right area on the Moon was difficult due to the low contrast of the Earthshine area," Veillet continued. "It helped me to have looked at the Moon before ... as I spent more than 10 years of my life in charge of the French lunar laser ranging station ... and also coordinating the international network of lunar laser ranging stations before coming to CFHT in 1996. It was like coming back in time by 15 years!"

In post-impact mode, Veillet said work is underway at CFHT to carry out more serious processing of the imagery to locate the impact site and check if dust was visible after the impact.

As for future lunar missions ending with an impact, Veillet advised: "The main thing is to make sure that somebody can observe it from Earth. The SMART-1 team prepared the final orbits to make sure [that] would indeed happen. We were lucky to be in the right

hemisphere at the right time. It will be very interesting to have others look at the SMART-1 impact site in the coming days with visible or infrared cameras and check if something is visible or not at the point of impact."

Sleep-starved

"It was a great experience," explained a sleep-starved Detlef Koschny, ESA planetary scientist and coordinator of the amateur campaign to watch for SMART-1's smashing finale on the Moon. He was stationed at the European Space Agency's Operations Center (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany.

"We had some last-minute issues to sort out with the data downlink ... the spacecraft went into a safe mode on Friday, just two days before [impact], but we recovered in record time. I was very excited about this spectacular end of mission," he told SPACE.com.

SMART-1's impact on the Moon not only tossed up lunar dust, but also gave rise to a few ideas for the future.

"There are still uncertainties in the precise shape of the Moon," Koschny noted. While he said that fact is a bit surprising, what's needed now is a laser altimeter orbiting the Moon to help size up the orb to a greater degree.

Koschny was pleased to see the HFCT imagery of the impact. Concerning the ground-based observations, he said he felt that many observers were not really prepared to observe the Moon. They didn't have adequate pre-crash practice sessions, he said, because many astronomers could not obtain enough observing time.

Observing time at major facilities is a precious commodity and can be oversubscribed with a variety of astronomical research agendas.

"We should allocate more time to telescopes for observing objects in the Solar System!" Koschny advised.

Olympic exploration

"We're looking forward to collecting the worldwide reports from this impact," said Bernard Foing, ESA's SMART-1 Project Scientist.

The call is out to the community to search for the ejecta blankets of lunar surface material stirred up from the crash, Foing said, "and for future lunar orbiters to search for the SMART-1 crater."

Foing said he was fortunate to follow SMART-1 from conception, development, launch, voyage, lunar capture, its science phase, and end of mission.

"It was in its destiny to end on the Moon ... and it was emotional to share this with observers and the public," Foing said. "I look forward to the future where we can pass the SMART-1 flame to the next nations in the olympic exploration of the Moon."

- The Impact Story

- Moon Image Gallery

- SMART-1: Mission Gallery

- Multi-Nation Moon Collaboration Backed

- The Grand SLAM: Rocketing Water to the Moon

- Top 10 Cool Moon Facts

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.