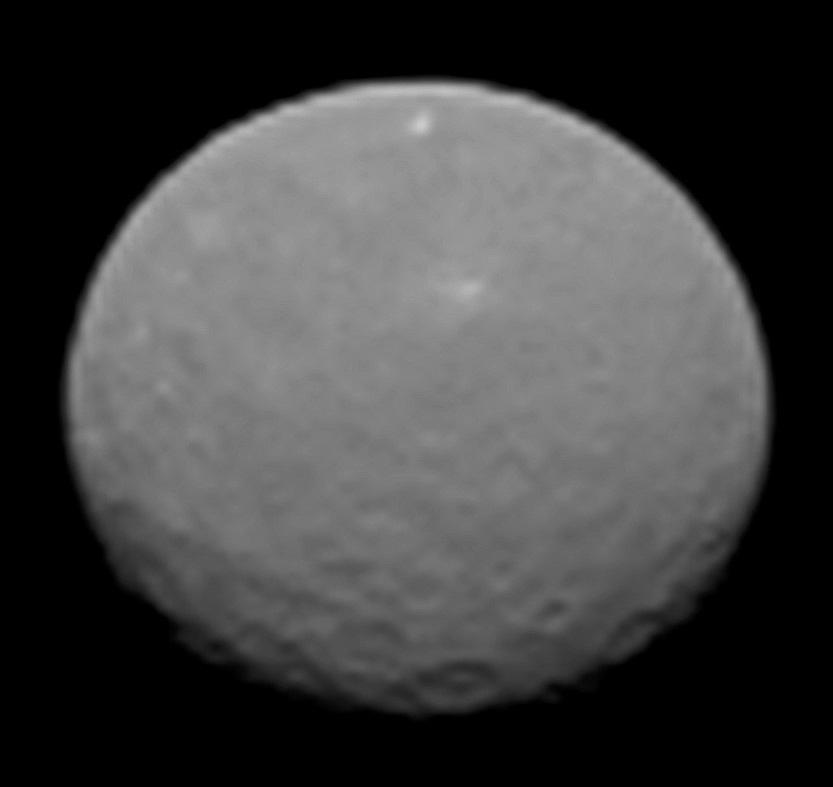

NASA's Dawn spacecraft has taken the sharpest-ever photos of Ceres, just a month before slipping into orbit around the mysterious dwarf planet.

Dawn captured the new Ceres images Wednesday (Feb. 4), when the probe was 90,000 miles (145,000 kilometers) from the dwarf planet, the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

On the night of March 5, Dawn will become the first spacecraft ever to orbit Ceres — and the first to circle two different solar system bodies beyond Earth. (Dawn orbited the protoplanet Vesta, the asteroid belt's second-largest denizen, from July 2011 through September 2012.) [Amazing Photos of Dwarf Planet Ceres]

"It's very exciting," Dawn mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman, who's based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said of Dawn's impending arrival at Ceres. "This is a truly unique world, something that we've never seen before."

Mysterious Ceres

The 590-mile-wide (950 km) Ceres was discovered by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in 1801. It's the only dwarf planet in the asteroid belt, and contains about 30 percent of the belt's total mass. (For what it's worth, Vesta harbors about 8 percent of the asteroid belt's mass.)

Despite Ceres' proximity (relative to other dwarf planets such as Pluto and Eris, anyway), scientists don't know much about the rocky world. But they think it contains a great deal of water, mostly in the form of ice. Indeed, Ceres may be about 30 percent water by mass, Rayman said.

Ceres could even harbor lakes or oceans of liquid water beneath its frigid surface. Furthermore, in early 2014, researchers analyzing data gathered by Europe's Herschel Space Observatory announced that they had spotted a tiny plume of water vapor emanating from Ceres. The detection raised the possibility that internal heat drives cryovolcanism on the dwarf planet, as it does on Saturn's moon's Enceladus. (It's also possible that the "geyser" was caused by a meteorite impact, which exposed subsurface ice that quickly sublimated into space, researchers said).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The interior of Ceres may thus possess liquid water and an energy source — two key criteria required for life as we know it to exist.

Dawn is not equipped to search for signs of life. But the probe — which is carrying a camera, a visible and infrared mapping spectrometer and a gamma ray and neutron spectrometer — will give scientists great up-close looks at Ceres' surface, which in turn could shed light on what's happening down below. [6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System]

For example, Dawn may see chemical signs of interactions between subsurface water, if it exists, and the surface, Rayman said.

"That's the sort of the thing we would be looking for — surface structures or features that show up in the camera's eye, or something about the composition that's detectable by one of our multiple spectrometers that could show evidence," he told Space.com. "But if the water doesn't make it to the surface, and isn't in large enough reservoirs to show up in the gravity data, then maybe we won't find it."

Dawn will also attempt to spot Ceres' water-vapor plume, if it still exists, by watching for sunlight scattered off water molecules above the dwarf planet. But that's going to be a very tough observation to make, Rayman said.

"The density of the water [observed by Herschel] is less than the density of air even above the International Space Station," he said. "For a spacecraft designed to map solid surfaces of airless bodies, that is an extremely difficult measurement."

Merging onto the freeway

Dawn is powered by low-thrust, highly efficient ion engines, so its arrival at Ceres will not be a nail-biting affair featuring a make-or-break engine burn, as most other probes' orbital insertions are.

Indeed, as of Friday (Feb. 6), Dawn is closing in on Ceres at just 215 mph (346 km/h), Rayman said —and that speed will keep decreasing every day.

"You take a gentle, curving route, and then you slowly and safely merge onto the freeway, traveling at the same speed as your destination," Rayman said. "Ion propulsion follows that longer, more gentle, more graceful route."

Dawn won't start studying Ceres as soon as it arrives. The spacecraft will gradually work its way down to its first science orbit, getting there on April 23. Dawn will then begin its intensive observations of Ceres, from a vantage point just 8,400 miles (13,500 km) above the dwarf planet's surface.

The science work will continue — from a series of increasingly closer-in orbits, including a low-altitude mapping orbit just 230 miles (375 km) from Ceres' surface — through June 30, 2016, when the $466 million Dawn mission is scheduled to end.

Rayman can't wait to see what Dawn discovers.

"After looking through telescopes at Ceres for more than 200 years, I just think it's really going to be exciting to see what this exotic, alien world looks like," he said. "We're finally going to learn about this place."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.