Planets Orbiting Red Dwarfs May Stay Wet Enough for Life

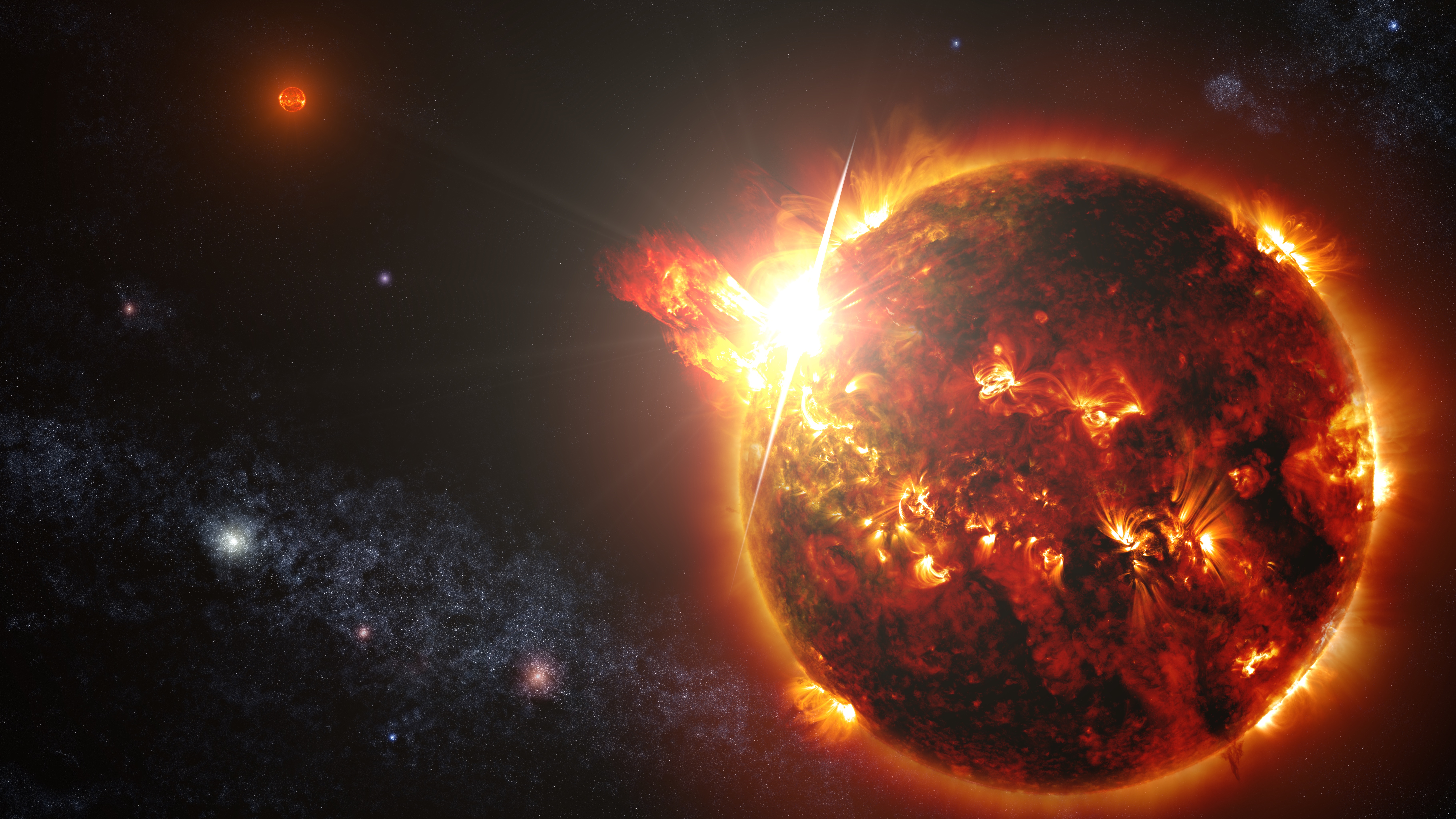

Small, cold stars known as red dwarfs are the most common type of star in the Universe, and the sheer number of planets that may exist around them potentially make them valuable places to hunt for signs of extraterrestrial life.

However, previous research into planets around red dwarfs suggested that while they may be warm enough to host life, they might also completely dry out, with any water they possess locked away permanently as ice. New research published on the topic finds that these planets may stay wet enough for life after all. The scientists detailed their findings online on November 12 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Red dwarfs, also known as M stars, are roughly one-fifth as massive as the Sun and up to 50 times fainter. These stars comprise up to 70 percent of the stars in the cosmos, and NASA's Kepler space observatory has discovered that at least half of these stars host rocky planets that are one-half to four times the mass of Earth. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

Red dwarf planets are potentially key places to search for life as we know it, not just because there are so many of them, but also because of their incredible longevity. Unlike our Sun, which will die in a few billion years, red dwarfs will take trillions of years to burn through their fuel, significantly longer than the age of the Universe, which is less than 14 billion years old. This longevity potentially gives red dwarfs a great deal more time for life to evolve around them.

Research into whether a distant world might host life as we know it usually focuses on whether or not it has liquid water, since there is life virtually everywhere there is liquid water on Earth, even miles underground. Scientists typically concentrate on habitable zones, the area around a star where it is neither too hot for all its surface water to boil away, nor too cold enough for all its surface water to freeze.

Recent findings suggest that planets in the habitable zones of red dwarf stars could accumulate significant amounts of water. In fact, each planet could possess about 25 times more water than Earth.

The habitable zones of red dwarfs are close to these stars because of how dim they are, often closer than the distance Mercury orbits the Sun. This closeness makes them appealing to astrobiologists, since planets near their stars cross in front of them more often, making them easier to detect than planets that orbit farther away.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, when a planet orbits very near a star, the star's gravitational pull can force the world to become "tidally locked" to it. When a planet is tidally locked to its star, it will always show the same side to its star, just as the Moon always shows the same side to Earth. This causes the planet to have one permanent day side and one permanent night side.

The extremes of heat and cold that tidally locked planets experience could make them profoundly different from Earth. For example, prior research speculated the dark sides of tidally locked planets would become so cold that any water there would freeze. Sunlight would make water on the sunlit side evaporate, and this water vapor could get carried by air currents to the night sides, eventually leading to sheets of ice miles thick on the night sides and removing all water from the sunlit sides. Life as we know it probably could not develop on the day sides of such planets. Although they would have sunlight for photosynthesis, they would have no water to serve as the primordial soup for life to swim in.

To see how habitable tidally-locked planets really are, scientists devised a 3D global climate model of planets that simulated interactions between the atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and land, as well as a 3-D model of ice sheets large enough to cover entire continents. They also simulated a red dwarf with a temperature of about 5,660 degrees Fahrenheit (3,125 degrees Celsius), and investigated whether all the water on these planets would indeed get trapped on their night sides. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

"I've been interested in trying to make calculations relevant for M-star planet habitability since being convinced by astronomers that these types of planets will likely be closest (in proximity) to Earth," said study co-author Dorian Abbot, a geoscientistat the University of Chicago.

For instance, the nearest known star to the Sun, Proxima Centauri, is a red dwarf, and it remains uncertain whether or not it has a planet. The possibility that red dwarf planets might be relatively near to Earth "means that anything geoscientists can tell astronomers about habitability of these planets will be essential for planning future missions."

The researchers simulated planets of Earth's size and gravity that experienced between 63 percent and 77 percent as much sunlight as Earth. They also modeled a super-Earth planet 50 percent wider than Earth with 38 percent stronger gravity, because astronomers have discovered super-Earth worlds around red dwarfs. For instance, Gliese 667Cb, a super-Earth at least 4.5 times the mass of Earth, orbits Gliese 667C, a red dwarf about 22 light years from Earth. They set this super-Earth on an orbit where it received about two-thirds as much as sunlight as Earth.

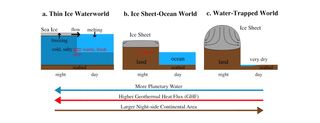

The researchers modeled three different arrangements of continents for all these planets. One was a water world with no continents and global oceans of varying depths. Another involved a supercontinent covering the night side and an ocean covering the day side. The last mimicked Earth's configuration of continents. The planets also had atmospheres similar to Earth's, but the researchers also tested lower levels of the greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, which traps heat and helps keep planets warm.

When it came to super-Earths covered entirely in water, and super-Earths with continental arrangements like Earth's, the researchers found it was unlikely that all their water would get trapped on their night sides. [The Search for Another Earth (Video)]

"This is because surface winds transport sea ice to the day side where it is melted easily," said lead study author Jun Yang at the University of Chicago.

Moreover, ocean currents transport heat from the day side to the night side on these planets.

"Ocean heat transport strongly influences the climate and sea ice thickness on our Earth," Yang said. "We found this may also work on exoplanets."

If a super-Earth has very large continents covering most of its night side, the scientists discovered ice sheets of at least 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) thick could grow on its night side. However, the day sides of these super-Earths would dry out completely only if they received less geothermal heat from volcanic activity than Earth, and had 10 percent of the amount of water on Earth's surface or less. Similar results were seen with Earth-sized planets.

"The important implication is that it may be easier than previously thought to keep liquid water on the dayside of a tidally locked planet, where photosynthesis is possible," Abbot said. "There are many issues that will affect the habitability of M-star planets, but our results suggest at least that water-trapping on the night side will only be a problem for relatively dry planets with large continents on their nightside and relatively low geothermal heat flux."

Based on present and near-future technology, Yang said it would be very difficult for astronomers to gauge how thick the sea ice or the ice sheets are on the night sides of red dwarf planets and test whether their models are correct. Still, using current and upcoming technology "it may be possible to know whether the day sides are dry or not," Yang said.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us