Mars on Earth? What Life Is Like on the 'Red Planet’

Kellie Gerardi is the business development specialist for aerospace firm Masten Space Systems and the media specialist for the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, a U.S. trade association advancing commercial human spaceflight. She lives with her husband in New York City and is determined to see boots on Mars, preferably her own. As a member of Mars Desert Research Station Crew 149, Gerardi contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Just beyond the faintest cellular signal in the Utah Desert, dwarfed by rock formations stained red from millennia of iron oxide dust, a white cylinder emerges. This is the Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS), one of the world's few analog Martian habitats, where a variety of national space agencies and scientists can simulate in situ resource utilization and analog Martian field research. [Lichen, Pizza and Mars Crew 149 (Gallery )]

Most recently, the prototype laboratory has brought together me, Belgian NASA Ames researcher Ann-Sofie Schreurs, Canadian educator Pamela Nicoletatos, American Medevac pilot Ken Sullivan, German trauma surgeon Dr. Elena Miscodan, American lawyer and locally-elected public official Paul Bakken, and Japanese microbiologist Takeshi Naganuma. Together, we are MDRS Crew 149, immersed in a complete spaceflight simulation, living and working in an analog Martian environment. [7 Most Mars-like Places on Earth]

We come from vastly different backgrounds and research areas, but our pilgrimage to the Martian habitat was predicated on the belief that space settlement is an achievable goal in our lifetimes. And we share a desire to help achieve that goal.

Power failure on "Mars"

When you enter the MDRS, you essentially have two choices: You can keep one foot in reality and do the bare minimum that the simulation demands, or you can suspend disbelief completely and steel yourself for the rigors of a truly hostile environment. Our crew committed to the latter, and we'll leave this rotation as stronger people because of it.

Although we had enough research projects to keep us cooped up in the Hab for years, we were surprised at the amount of time and energy we had to spend on basic survival. Early on, we experienced a complete loss of power, fuel and communications.

The inconvenience of losing electricity and the functionality of our sole working toilet paled in comparison to the emergency that our lack of water presented. We immediately implemented strict rationing of our emergency reserves, and we completed an engineering EVA (ExtraVehicular Activity) to transform one of our rovers into a temporary generator. We constructed a field latrine for toilet use, and we had enough stored solar power to run a few small personal devices for emergency contact with mission control.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once we had our basic daily survival under control (monitoring the diesel tanks, rationing water and reconstituting freeze-dried food), we turned our attention to research.

Life on "Mars"

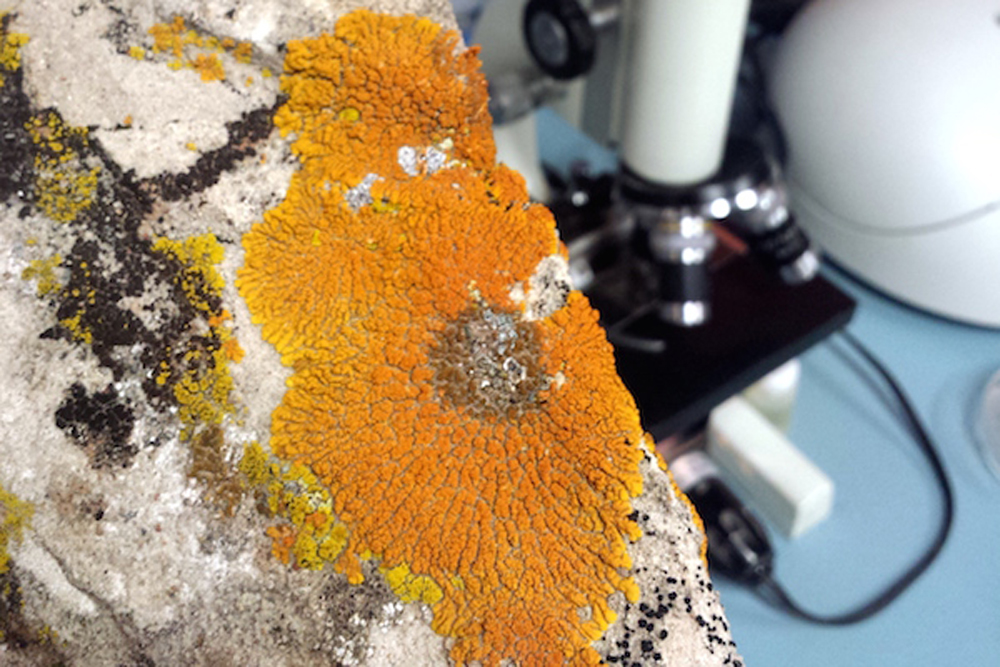

Under the guidance of Naganuma, who is responsible not only for the discovery of new species, but for entirely new classes of species, we set out on scientific EVAs to search for lichen colonies in the nearby area and collect samples. Lichens are the most resistant organisms on Earth, and whenever new land or ice sheets form, these creatures are the first settlers. This was an activity to simulate Mars explorers' efforts to find basic signs of life, but it will also serve to further our understanding of basic terraforming capabilities.

Through the use of a centrifuge in the lab, we separated out the samples. In the coming weeks, we will use a sequencer to identify any extremophiles and cyanobacteria. Some people believe cyanobacteria should be sent to Mars in an early terraforming effort, due to their ability to photosynthesize. But cyanobacteria alone won't be enough: They'll need protection from harmful UV rays and an ability to retain humidity for growth. Our lichen colonies could provide perfectly resilient "housing." As a bonus, we may have even stumbled upon a new species of bacteria that can aid lichen growth. Time and a sequencer will tell. [Mock Mars Mission: Learning New Skills for Red Planet Living ]

We've also had fun with our research. In a plant growth study with ORBITEC JSC Mars-1A Regolith Simulant, aka Mars dirt, we forced growth of both sorghum and hops. The academic reasoning is that sorghum is a high-nutrient grain with relatively low water needs, and hops are used as medicinal herbs, making these crops potentially useful to Mars explorers. The fun reasoning is that sorghum and hops are also two main ingredients in beer, and their germination and root establishment in Martian soil simulant has allowed us to academically prove that one can produce beer on Mars. We hope to help make the planet just slightly more appealing.

Transitioning from simulations to missions

In my day job with Masten Space Systems, we advance the pinpoint accuracy necessary to land rockets safely at off-Earth settlements. My personal research here at the MDRS gives me an understanding of what sort of in situ resource utilization techniques those settlements might employ: I've participated in geological surveying of the area for natural resources, searched for the most basic signs of life, and made a home out of a hostile environment.

Our research expedition has been an incredible experience, and when I leave here in five days, I'll return home even more committed to doing everything in my power, both personally and professionally, to help expand humankind's presence in the solar system.

My crew feels the same way. Besides our mutual commitment to advancing the space exploration capabilities of humankind, we also have something else in common: At one point, we had all applied to join the Mars One mission; the nonprofit company proposes to send four humans on a one-way ride to the Red Planet in 2024.

Did any of us think that Mars One candidates would be strapping into a rocket in 10 years? No, we realized that it was extremely unlikely. Did we all agree that we, as a species, need to be making real progress toward that goal? Yes. Mars One is not an aerospace company. They're a nonprofit organization with a single media premise, attempting to close a multi-billion-dollar business case through broadcast rights, and hoping that the spectacle of sending humans to Mars will raise enough publicity dollars to pay for the hardware to accomplish the feat. Where my crew and Mars One found common ground was in the simple agreement that the major barriers to human settlement of Mars are largely economic, rather than engineering related. [Living the Life on 'Mars' (Gallery )]

We all agree that space settlement is an achievable goal in our lifetimes, and anyone who proposes to try to close the business case has our full attention.

Ironically, toward the end of our time here at the MDRS, the Mars One candidate results were publicly announced, and emails trickled in slowly to our personal devices.

"We regret to inform you that you will not proceed to the next selection round," the emails began. "This is not the end of your dream!" they assured us, bolded for effect or comfort. One by one, our entire crew received the same message. That night, over a meal of macaroni and reconstituted-cheese, we shared a laugh and agreed that if we had a stronger Internet connection, we would have replied directly to the email, telling them that there must be some mistake — we had already made it to Mars! And we're just getting started.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.