Mysterious Mars Plume Discovery Is Amateur Astronomy at Its Best

A mysterious plume of material reaching high into the Martian atmosphere has scientists buzzing about the Red Planet — and they have amateur astronomers to thank for spotting the baffling feature.

Wayne Jaeschke is a patent lawyer by day, but most nights, you can find him in his observatory, pointing a telescope skyward. In March 2012, Jaeschke spotted what looked like a dust cloud popping off the surface of Mars. Two years later, he is a co-author on a scientific paper investigating the nature of the perplexing Mars plumes.

"You know, 999,999 times out of a million, when the amateur astronomers see something in an astronomical photo, the professionals have seen it as well, or they have a theory for explaining it," Jaeschke said. "But this is a rare case where no one has been able to explain it." [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Army of amateur astronomers

Jaeschke started observing the sky when he was just a kid. He learned about the cosmos from a family friend who went on to lead the astronomy department at Stanford University. Though he never pursued astronomy as a career, over the years, it grew into a serious hobby.

"About 10 years ago, I started to image the planets on a daily basis," Jaeschke said.

Thanks to the reduced cost of high-quality cameras, data storage, photo editing software — and, of course, quality telescopes — amateur astronomers like Jaeschke can take high-quality sky images every night, and gradually build up huge volumes of data.

Over the years, Jaeschke has built up an email list of both amateur and professional astronomers who want to hear about his work.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The more data you produce, the more people get interested — particularly professionals, because they can't look at [the planets] all the time," Jaeschke said (even the fleet of orbiting satellites around Mars can't watch every inch of the Red Planet all the time). "So, they turn to the amateur community."

Professional astronomers can use these daily photographs to do things like monitor daily changes in a planet's weather, he said. In some instances, professionals and amateurs collaborate on targeted observations.

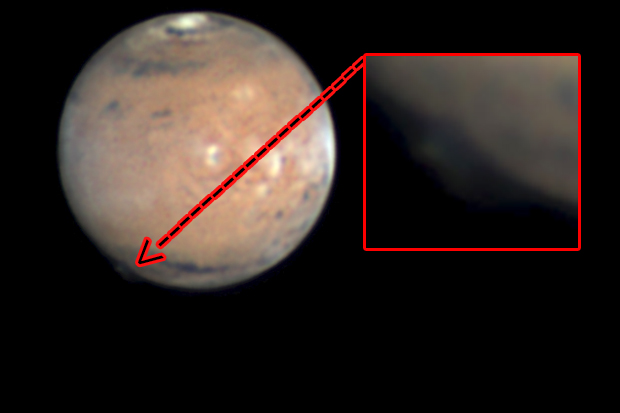

On the night of March 19, 2012, Jaeschke was taking images of Mars per his usual routine, when he noticed "a little blob" on the side of the planet. He assumed it was a technical issue — perhaps a problem with one of the monitors, or even just a speck of dust on one of the lenses.

"I didn't think much of it until the next day, when I took the video and turned it into photos," Jaeschke said. If the blob were caused by an issue with one of the screens or one of the lenses, it would appear in the same place on each photo.

"I took a number of consecutive images over time and created an animation," Jaeschke said. "When I saw the feature was rotating with the planet, I knew it had to be a feature on the surface of Mars."

Jaeschke sent the images out to his mailing list and posted about them on astronomy message boards. He asked if anyone else had seen the spot. Both amateur and professional astronomers began responding.

"I asked people who had taken pictures of Mars to check their data, and many people came back and posted their images and said, 'Yeah I found it,'" Jaeschke said. "Eventually, the word was out to look for [the plumes]. With this community, you get this army of amateur astronomers. You tell them to go get a picture of a planet, and they do." [Become an Amateur Astronomer: Tools, Tips and Equipment]

Eventually, Jaeschke would collect 18 independent observations that confirmed the presence of the Martian plumes. The find was so extraordinary that, like Jaeschke, many people had assumed it was a mote of dust or a problem with the equipment.

"One guy said he Photoshopped it out of a picture because he thought it was an error," Jaeschke said.

Along with Jaeschke, amateur astronomers Damian Peach, Don Parker, Marc Delcroix and Christophe Pellier are co-authors on the new paper. Jaeschke said the confirmation of the plumes would not have happened without the amateur community and that it was crucial that he had so many people with whom to compare his finding.

Mystery of the plume

Agustin Sánchez Lavega, a researcher at the University of País Vasco in Spain, has been in contact with Jaeschke for about four years, and has used Jaeschke's data in the past. Lavega saw the photos of the plumes and, along with a small group of colleagues, began to investigate.

Just like Jaeschke and the amateur astronomers, the scientists first focused on determining whether the plumes were an error — for example, an illusion caused by light, or a problem with the technology.

"We had to check this again and see if it was real," said Antonio García Muñoz, a researcher with the European Space Agency and a co-author on the new paper. "Eventually, we came to the conclusion that this is real and we have to [move] forward with [the analysis]. We were very excited. I mean, we don't know what we're seeing." [Photos of Mars: The Amazing Red Planet]

The new paper, which appeared in the Feb. 16 issue of the journal Nature, confirms that the plumes are a real feature on Mars. They reached altitudes of up to 155 miles (250 kilometers) above the surface of the planet, and cover an area of up to 310 miles by 620 miles (500 km by 1,000 km). They remained visible for 10 days but changed shape over that time.

Shorter plumes have been reported on the surface of Mars before, reaching altitudes of 62 miles (100 km). The researchers went back through data from the Hubble Space Telescope and found another abnormally high plume that appeared on Mars in 1997, according to a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA).

At 155 miles above the Martian surface, atmosphere of Mars is thought to be extremely thin, according to García Muñoz said. A thin atmosphere cannot hold on to particles of material, which means clouds of dust or other heavy molecules are unlikely to form. For this reason, the researchers say they have mostly rejected the idea that the plume was caused by a meteorite crashing into the surface of the planet.

The idea that the plume is actually a cloud of water or carbon dioxide runs into problems as well, regarding both the thickness and the temperature of the Martian atmosphere.

An alternative explanation is that the plume is caused by an aurora, just like the northern and southern lights on Earth. Scientists have observed auroras on Mars — in fact, the location of the plume is a spot where aurora activity has been observed. But once again, García Muñoz said, aurora activity is usually at much lower altitudes than where the plumes are located.

Beyond these proposals, the researchers cannot say what the plumes are.

"What will really move this forward is more observations, which is kind of difficult because we don't know how often these things happen," García Muñoz said. "We cannot apply for time on a [professional] telescope to look for these things, because we don't know when it will happen."

There are satellites orbiting Mars that may have detected data on these types of plumes in the past, and García Muñoz said scientists are digging through old data sets, looking for clues.

But ideally, a professional-grade instrument will be able to observe the massive plumes in real time. It's possible that amateur astronomers could alert professional astronomers if another plume were to appear.

"When something changes, when something different appears, we contact professionals and let them know," Jaeschke said.

But on the vast majority of nights, Jaeschke and other amateur astronomers won't see anything of note. Still, they keep their eyes peeled for the one-in-a-million night when there is something to see.

"I've been out there literally hundreds of times," Jaeschke said. "A lot of nights, you go out there, and you see nothing, and you stand out in the cold and you know they're not going to be great pictures — but you don't want to miss something. Once in a great while, it's really rewarding."

The discovery of the Mars plume "really helps to stimulate the amateur community," he added. "It shows that I don't need to be a professional astronomer to contribute to something I love," he said. "It's just a matter of being dedicated."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter