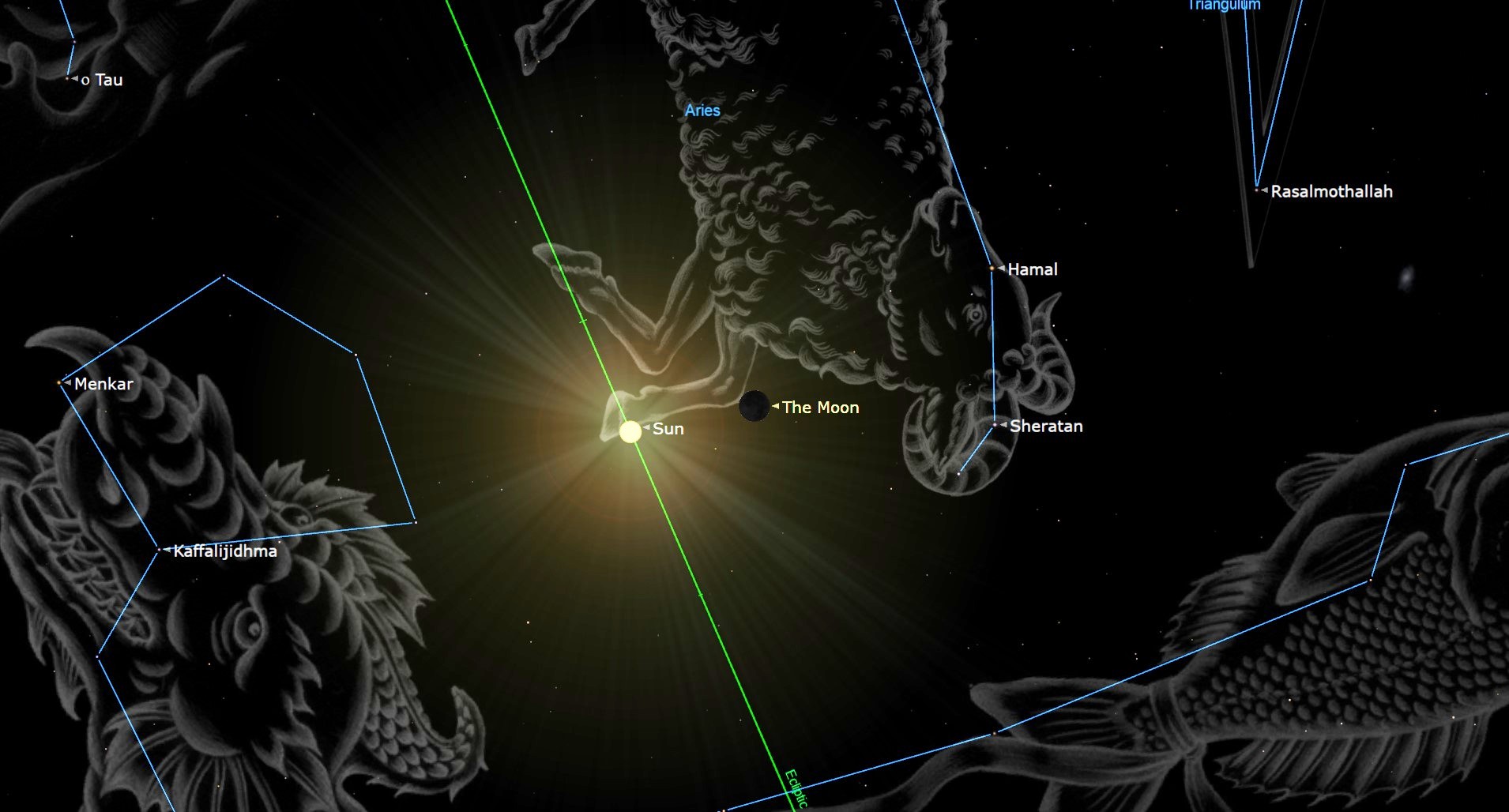

Fierce 'Superflares' from the Sun Zapped the Infant Earth

Our young sun may have routinely blasted Earth with gobs of energy more powerful than any similar bombardments recorded in human history.

Huge bursts of these particle and radiation "showers" ignited by these so-called "superflares" could have penetrated Earth's protective magnetic fields and bathed our planet's atmosphere, a new study has shown. Superflares, therefore, likely had profound impacts on the development of life on our planet.

The findings stem from a growing set of observations of other stars like the sun. NASA's Kepler spacecraftspotted the brightening characteristic of flares in sunlike stars it monitored for over four years. Although flares commonly erupt from the sun and it appears other stars as well, frequency does not render these stellar explosions any less impressive. [The Worst Solar Storms in History]

"Solar flares represent the most violent eruptions in the solar system," said Vladimir Airapetian, senior astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and a research professor at George Mason and Capella Universities. "They release energy comparable to a couple billion megatons of TNT in a few minutes."

Airapetian was the lead author of a new paper on the findings appearing in the Proceedings of 18th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems, and the Sun Proceedings of Lowell Observatory.

The Kepler data, along with observations of two sunlike stars by Japanese astronomers, have revealed that the sun's documented spasms might be rather mild and rare in modern times, fortunately for us.

'The Big One'

The biggest flare event in recent history was the so-called Carrington eventin 1859, named after the British astronomer Richard Carrington. He documented a brightening of the sun near a group of sunspots — often the site of flares — that preceded an incredible auroral display. Astonished skygazers reported the colorful Northern Lights as far south as the Caribbean.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Aurorae are caused by particles of air getting charged up by energy from the flaring sun as it floods into the atmosphere at Earth's poles. In the Carrington event, this overflow of energy also induced electric currents in telegraph wires, causing sparks and even setting equipment on fire, according to reports from the time.

Based on the Carrington event and smaller, more recent sun-spawned disruptions, many scientists and policymakers worry about a devastatingly powerful flare crippling our technology-dependent, modern society.

Airapetian's study affirmed these concerns as justified. Observations of 279 sunlike stars detected signs of brightening comparative in size to the Carrington event, but also superflares on the order of 10,000 times stronger than any flares known to have been unleashed by the sun. [Stunning Photos of Solar Flares & Sun Storms]

"This discovery is hard to overestimate," said Airapetian, "because it may uncover the 'hidden powers' of our sun in the past, near or far future."

Unruly youth

Other research has found that young sunlike stars, much like young human children, are particularly prone to throwing tantrums. Early in their lives, stars rotate faster and are more magnetically active — conditions ripe for flare eruptions.

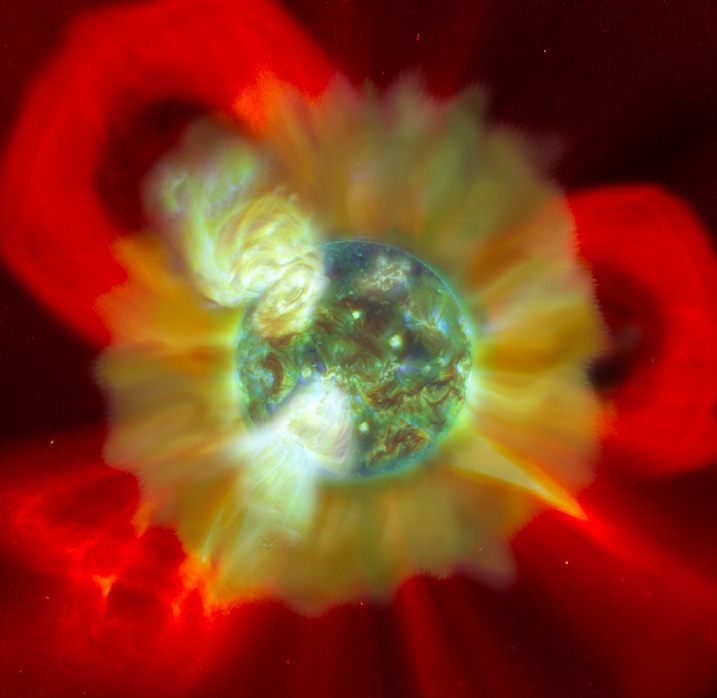

Flares arise when magnetic field lines emanating from the sun, which normally form rubber-band-like loops, snap and reconnect, experiencing a sort of "short circuit," as Airapetian calls it. A burst of lethal doses of solar radiation as well as the sun's constituent charged gas, or plasma, often spews out into space. When the latter is involved, the flare is said to have hurled a coronal mass ejection, or CME.

Very active stars yield stronger and more frequent flares and CMEs. Airapetian said that according to his research team's calculations, the young sun in its first several hundred million years of life could have cranked out an astounding 250 superflares per day.

Of course, then as now, most superflares and associated CMEs would have missed Earth, a relatively small target in the solar system. Still, statistically speaking, it looks likely that early Earth took the brunt of a solar blast more powerful than the Carrington event at the shocking rate of at least once a day — and for half an eon.

An energetic rain

To get a sense of the effects on early Earth from this sort of, as Airapetian put it, "fast and furious” superflare and super-CME bombardment, he and his team built computer models. The models simulated a relatively conservative super-CME, only about twice that of the Carrington event's potency, and had it smash into a model of the Earth's magnetosphere and upper atmosphere.

For simplicity's sake, Airapetian assumed that Earth had developed a magnetic field of similar intensity as today's about 500 million years after its birth, shortly following the sun's genesis 4.6 billion years ago. The presence of this field would probably have overlapped for a time with the sun's youthful superflare activity. Life, perhaps not incidentally, is thought to have emerged about 3.8 billion years ago, after the magnetic field's formation.

According to the new study, early Earth's magnetic field would have buckled under the raging sun's onslaught.

"In our paper, we have shown that a super Carrington-type CME event would have greatly compressed the magnetic field," said Airapetian. "This would ignite huge electric currents on Earth and let energetic particles penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere and surface."

Giver, or taker, of life?

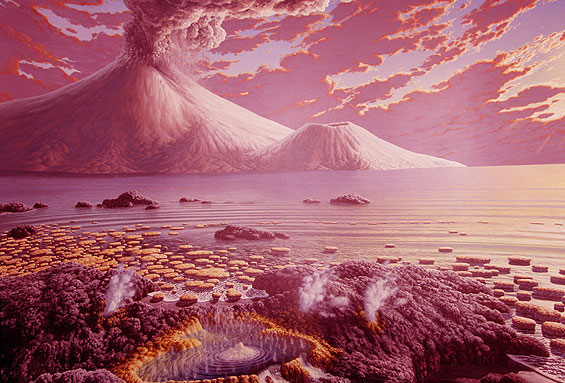

What exactly this radiation would have done to hinder or perhaps, counterintuitively, help life's rise, is debatable. The timing of a modicum of protection against the superflaring young sun, thanks to a magnetic field, suggests the complexity of life's self-replicating chemistry could not have withstood the young sun's energetic interference.

However, continuing research by Airapetian suggests superflares and CMEs from the sun might have been integral to life's rise. Such energetic radiation could have broken apart nitrogen molecules with very tightly bound atoms in the early Earth's atmosphere into free, individual nitrogen atoms. From the perspective of chemistry, nitrogen atoms bond well with other atoms.

Thus set free by superflares, the nitrogen atoms could have then combined with hydrogen and carbon, creating "organic molecules that can set favorable conditions for creating the building blocks of life," said Airapetian. Furthermore, the nitrogen atoms could have combined with hydrogen, forming ammonia in the atmosphere, a greenhouse gas that might have played an important role in warming the early Earth.

It's been a longstanding mystery how inert, molecular nitrogen in early Earth's atmosphere ever broke down into atomic nitrogen. Life performs this task all the time, but it begs the chicken-or-the-egg scenario of how life ever formed without available nitrogen, and how nitrogen was ever available without life. Superflares might provide the answer.

"On one hand, our studies suggest that the harsh conditions introduced by intensive radiation from flare and CME activity had a detrimental effect on life," he said. "On the other hand, high levels of steady, intense radiation could have opened a 'window of opportunity' for the origin of life on Earth by setting a stage for prebiotic chemistry it requires."

Airapetian and colleagues have continued digging into these implications and promise new results soon.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Follow Space.com @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Adam Hadhazy is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He often writes about physics, psychology, animal behavior and story topics in general that explore the blurring line between today's science fiction and tomorrow's science fact. Adam has a Master of Arts degree from the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Boston College. When not squeezing in reruns of Star Trek, Adam likes hurling a Frisbee or dining on spicy food. You can check out more of his work at www.adamhadhazy.com.