US Military Satellite Explosion No Threat to European Space Missions

The debris from the military weather satellite that exploded in orbit last month doesn't pose a threat to any nearby European missions, officials with the European Space Agency have said.

The U.S. Air Force's Defense Meteorological Satellite Program Flight 13 (DMSP-F13) broke up into 43 pieces on February 3. After 20 years in orbit, the satellite experienced a power system failure that sparked a silent space explosion.

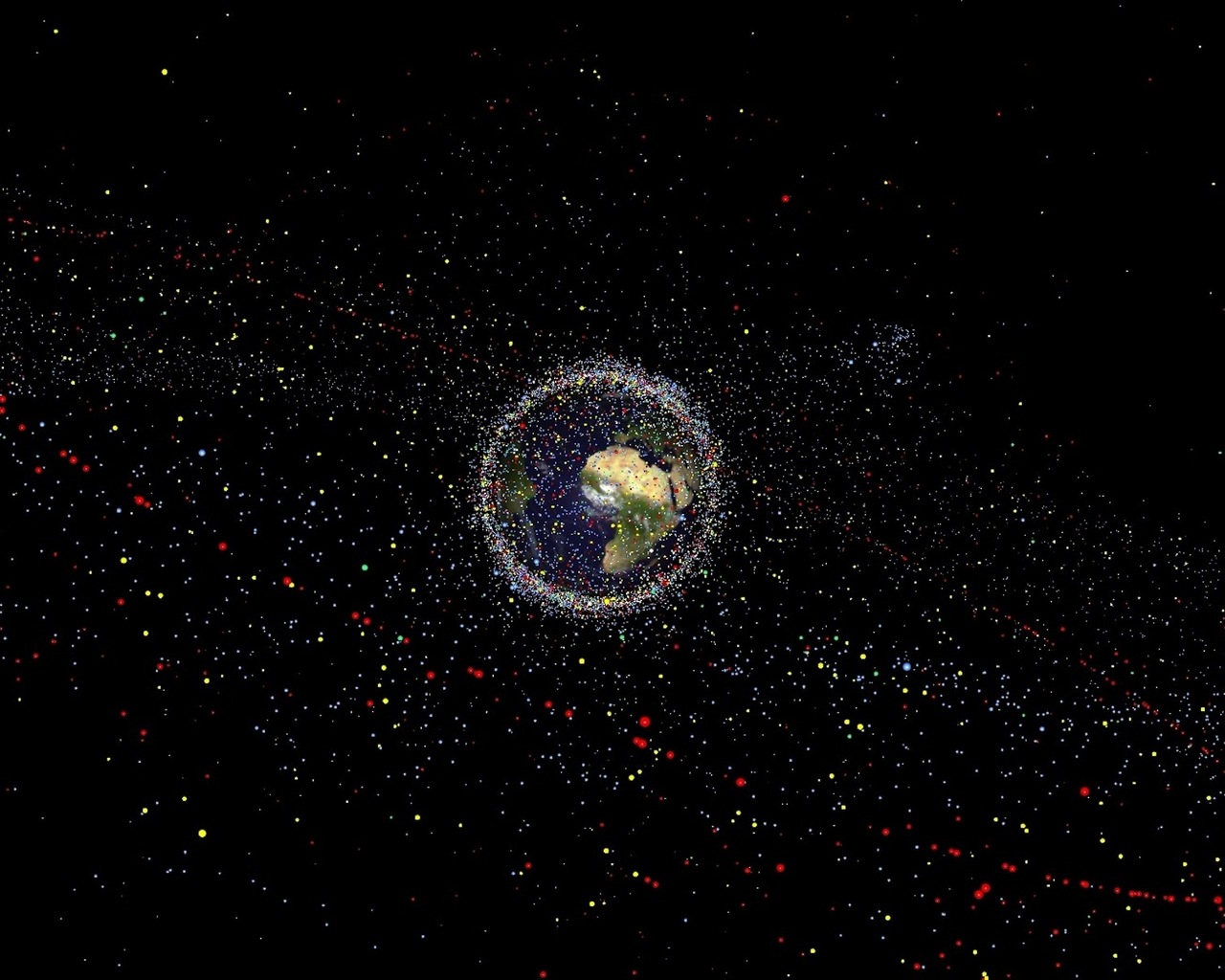

The break-up adds more debris, or space junk, into low-Earth orbit. Because Earth-gazing missions and some communication satellites commonly use the part of space where the explosion occurred, any extra debris poses a threat to other satellites in orbit. The European Space Agency (ESA) needed to better analyze the satellite situation in order to assess the potential risk, but the agency has found no threat to their nearby instruments.

The dispersion of the debris associated with DMSP-F13 event is fairly large. But luckily, the largest concentration of fragments resides near the original altitude of the satellite — about 62 miles (100 kilometers) above ESA's satellite concentration and 43 miles (70 km) above ESA's nearest satellite: CryoSat-2.

"The event is not considered major," Holger Krag, of ESA's Space Debris Office, said in a statement. "Should the reported number of fragments stabilize at this level, we can consider it to be within the range of the past 250 on-orbit fragmentation events."

Nonetheless, it demonstrates well why ESA created a Clean Space Initiative to investigate technologies that could mitigate space junk. According to the agency, more than 4,800 total launches have placed some 6,000 satellites into orbit, of which less than a thousand are still operational today.

That leaves more than 5,000 dead satellites in orbit around the Earth. Over time, they'll collide — likely creating a chain reaction of collisions — or decay — slowly falling back to the Earth. Unless, of course, they're removed from orbit.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"International regulations state that low-orbiting satellites are removed within 25 years of their mission end-of-life," Luisa Innocenti, heading the Clean Space Initiative, said. "Either they should end up at an altitude where atmospheric drag gradually induces reentry, or alternatively be dispatched up to quieter 'graveyard orbits.'"

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Shannon Hall is an award-winning freelance science journalist, who specializes in writing about astronomy, geology and the environment. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Nature, Quanta and elsewhere. A constant nomad, she has lived in a Buddhist temple in Thailand, slept under the stars in the Sahara and reported several stories aboard an icebreaker near the North Pole.