Astronomy's Oldest Known 'Nova' a Cosmic Case of Mistaken Identity

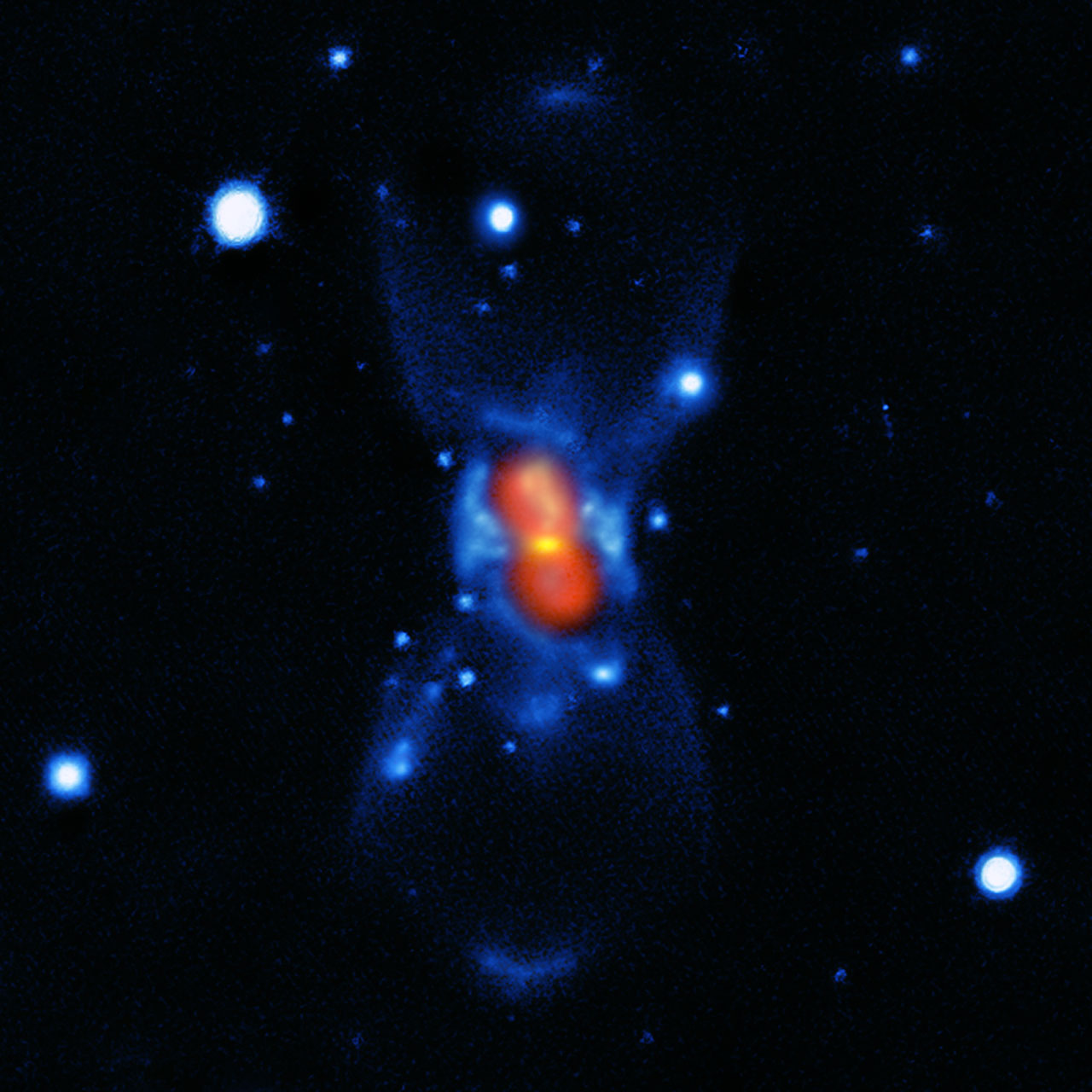

Cosmic detectives are investigating a case of mistaken stellar identity: An exploding star that was once thought to be the oldest recorded nova — a nuclear explosion on the surface of a dead star — was more likely caused by the merger of two stars.

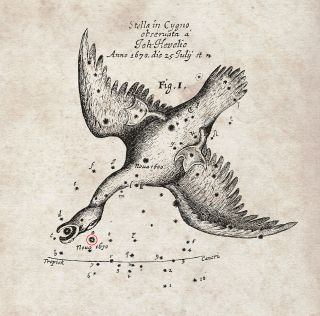

In 1670, a bright new star appeared in the constellation Cygnus, the Swan, and stayed there for two years — you can see the location of the new stars in this video. The short-lived star was grouped into the "nova" category, but over the last 30 years, astronomers have been questioning its identity.

A new research paper that examines the chemical makeup of the crime scene may be the final nail in the coffin. The researchers suggest that the so-called nova is instead the oldest example of another type of stellar explosion sometimes called a "red nova" — a somewhat newly-discovered phenomenon that scientists are still working to understand. [Photos of Supernova Star Explosions]

A new star in the sky

In 1670, a new star appeared just above the head of the swan that makes up the constellation Cygnus. Many astronomers took note of this newcomer, so its appearance and life span are well documented. It was dubbed Nova Vul 1670 —at the time, "nova" referred simply to any new star.

In the last 300 years, however, the word "nova" has taken on a much more specific and scientific meaning.

By today's definition, a classic nova is an explosion that takes place on the surface of a white dwarf — the small, dense, nugget of leftover material from a star that has stopped burning. The white dwarf syphons material away from another nearby star, the pressure builds up on its surface and a nuclear reaction releases an incredible burst of energy. (Unlike Type Ia supernovas, which start in a similar fashion, the white dwarf in a nova is expected to survive through the explosion.)

Many things about CK Vulpeculae's identity as a nova just don't line up, said Tomasz Kaminski, a postdoctoral fellow at the European Southern Observatory.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For example, novas tend to burn in the sky for days — not years, as CK Vulpeculae did. Plus, the new star of 1670 didn't disappear right away. After two years, it faded, then reappeared, then faded for good — which is very unusual for a nova, Kaminski said. And observations have shown that CK Vulpeculae's temperature is much lower than that of a nova, where the radiation from the nuclear reaction continues to generate heat after the explosion is done, Kaminski said.

The new study, which is detailed in the March 23 edition of the journal Nature, may finally strip CK Vulpeculae of its "nova" title. Kaminski and his co-authors looked at the different molecules present in the wreckage of CK Vulpeculae, and found a profile that they say cannot be created by a classical nova.

But if CK Vulpeculae isn't a nova, then what is it?

Red nova

In the new paper, Kaminski and his colleagues argue that CK Vulpeculae is a phenomenon with multiple names in scientific literature. They've been called red novas, red transients, luminous red transients and intermediate luminous optical transients (ILOTs), among others.

"People who study these red nova realized all the observations we have of these objects can be explained only if they explode as [an] effect of a collision and a merger of two stars," Kaminski said.

The notion that a red nova could be a unique category of stellar explosion took hold in 2008, when astronomers watched two stars in a system orbit in toward each other and produce an explosion with the characteristics of a red nova, Kaminski said.

"Many of the novae we know from historical records could be this type; it's just that people observe them during the outburst, and then no one really cared what happened with them," Kaminski said. "And that's why they didn't realize maybe we're dealing with some new phenomenon."

Previous groups have suggested that CK Vulpeculae is a red nova. What Kaminski and his group have provided is the first look at the molecular profile of one of these objects, which he said is distinct from other stellar explosions. [Star Quiz: Test Your Stellar Smarts]

"This is a major step," he said. The chemical profile shows the presence of molecules and isotopes that are strange compared to other types of stellar explosions, including classical novas, Kaminski said. In fact, the profile is actually somewhat unique among red nova, which may be a product of CK Vulpeculae's age — perhaps something happens in these red novas over time that produces a unique bouquet of chemicals, he said.

Kaminski cautioned that scientists are still working to demonstrate that red novas are, in fact, the products of stellar mergers.

Noam Soker, an astrophysicist at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, was one of the scientists who previously suggested that CK Vulpeculae was a red nova. He and some of his colleagues have theorized that red novas are not the result of sudden stellar mergers, but rather are produced by the gradual accretion of matter from one star to another. He and Kaminski said one thing that would help clarify the cause of a red nova would be observations inside the clouds of debris, to see the stars that remain there.

Kaminski said that, right now, the available evidence suggests that CK Vulpeculae is a red nova. But it's possible that in 10 years, someone will come up with a different explanation for how this stellar explosion came to be.

"This is science and astronomy: You propose something new, and everyone is welcome to find supporting evidence, or disprove it with some new theory or new observations," he said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter