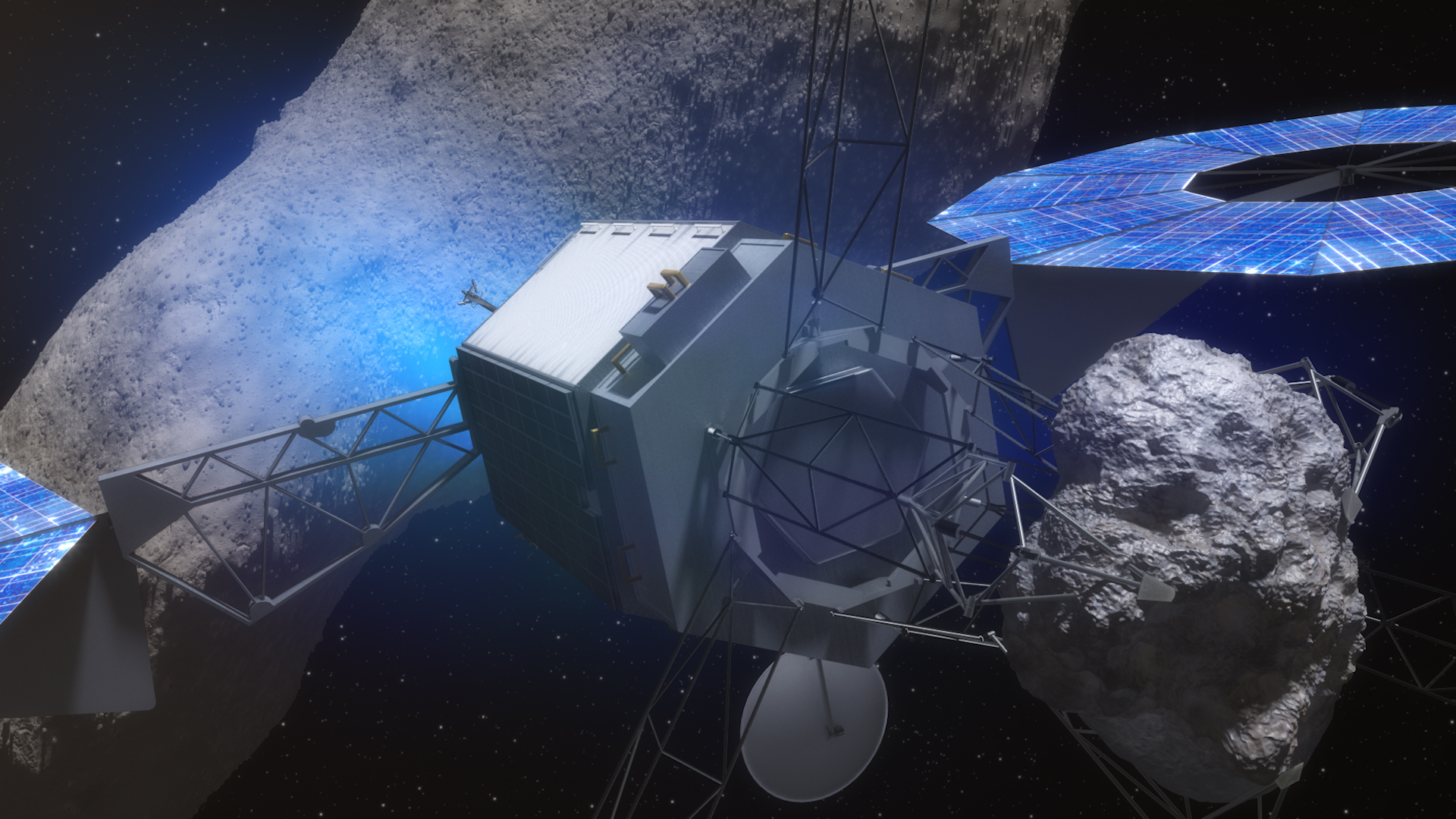

NASA's bold asteroid-capture mission will pluck a boulder off a big space rock rather than grab an entire near-Earth object, agency officials announced today (March 25).

NASA intends to drag the boulder to lunar orbit, where astronauts will visit it beginning in 2025. The space agency decided on the boulder snatch — "Option B," as opposed to the whole-asteroid "Option A" — Tuesday (March 24) during the mission concept review of the asteroid-redirect effort, NASA Associate Administrator Robert Lightfoot told reporters during a teleconference today.

Option B will probably cost about $100 million more than Option A would have, but its advantages are worth the price-tag bump, Lightfoot said. [NASA's Asteroid Capture Mission in Pictures]

For example, large asteroids are known to harbor multiple boulders, so the mission will have a number of targets to choose from when it gets to the big space rock. Option A is riskier; the capture probe would likely have no recourse if its chosen asteroid proved too large to handle, or otherwise unsuitable.

Option B will also help develop more of the technologies humanity needs to extend its footprint beyond Earth, Lightfoot said.

"We are really trying to demonstrate capabilities that we think we're going to need in taking humans further into space, and ultimately to Mars," Lightfoot said. "That's what we're looking at."

The asteroid plan

As currently envisioned, NASA's Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM) will launch a robotic probe in December 2020.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

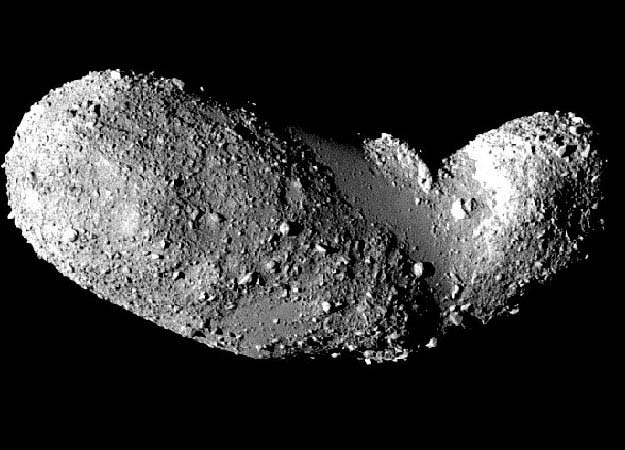

After about two years of spaceflight, the craft will rendezvous with a large near-Earth asteroid. NASA hasn't decided yet which space rock to target, and the decision doesn't have to be made until a year before launch, but the leading contender at the moment is the roughly 1,300-foot-wide (400 meters) 2008 EV5, agency officials said today.

The capture probe will assess the chosen asteroid's boulders, grab one up to 13 feet (4 m) wide and then retreat to a "halo orbit" around the big space rock. The spacecraft will stay in this orbit for 215 to 400 days, long enough for the boulder-toting probe's subtle gravitational tug to influence the orbit of the larger space rock.

This aspect of the mission should help researchers learn more about how to deflect asteroids that may pose a threat to Earth, Lightfoot said.

"Once we understand we've actually influenced the larger asteroid, then that gives us an idea — OK, how much more do we want to do that, or do we want to start heading back?" he said.

The capture probe will then turn around and head toward lunar orbit, where it should end up by late 2025. Two NASA astronauts will then journey out to meet the robotic spacecraft and the boulder, using the agency's Orion capsule and Space Launch System megarocket, both of which are in development. This manned mission will likely last 24 or 25 days, Lightfoot said.

The cost of the robotic component of ARM — that is, the capture/redirect mission, without any astronaut visits —will be capped at $1.25 billion, not including the launch vehicle.

Getting the show on the road

Now that the mission-concept review is done and NASA has settled on Option B, the next big milestone for ARM is an "acquisition strategy meeting" in July.

"This is where we'll decide how we're going to procure all these systems," Lightfoot said, citing the solar-electric propulsion system that will power the ARM capture probe as one prominent example. "We've got to get those pieces moving."

He's happy that ARM has put the design uncertainty in the rearview mirror.

"Let's get on with it, so we can get this next key step in our journey to Mars moving on," Lightfoot said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.