Dark Matter Probably Isn't a Mirror Universe, Colliding Galaxies Suggest

Dark matter may not be part of a "dark sector" of particles that mirrors regular matter, as some theories suggest, say scientists studying collisions of galaxy clusters.

When clusters of galaxies collide, the hot gas that fills the space between the stars in those galaxies also collides and splatters in all directions with a motion akin to splashes of water. Dark matter makes up about 90 percent of the matter in galaxy clusters: Does it splatter like water as well?

New research suggests that no, dark matter does not splatter when clusters of galaxies collide, and this finding limits the kinds of particles that can make up dark matter. Specifically, the authors of the new research say it is unlikely that dark matter is part of an entire "dark sector" — a mirror version of the visible universe. [Dark Matter: A Cosmic Mystery Explained (Infographic)]

Colliding galaxy clusters

Our galaxy contains hundreds of billions of stars, and there are hundreds of billions of galaxies in the observable universe. There's also a lot of gas and dust between the stars and the galaxies. But all of those stars, galaxies, gas and dust make up only about 10 to 15 percent of the matter in the universe.

The other 85 to 90 percent is dark matter. Scientists don't know what dark matter is made of or where it comes from, only that it doesn't appear to reflect or radiate light. It does, however, exert a gravitational pull on the regular matter around it.

David Harvey, a postdoctoral researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, is one of many scientists currently trying to figure out what dark matter is made of. There are lots of ways to go about this, and Harvey decided to see what happens when dark matter collides with itself.

To do this, Harvey and his colleagues at the University of Edinburgh, where Harvey did his PhD work, looked at collisions among entire clusters of galaxies, where as much as 90 percent of the mass involved in the collision is dark matter, according to a statement from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"[Galaxy cluster mergers] are incredibly messy," Harvey said. "You've got [the stars], the highest densities of dark matter and hot gas all swirling together."

Scientists have tried to use these galaxy cluster crashes to study dark matter for decades, but improved techniques for observing the different components of those mergers has inspired a revival, he said. "We wanted to have a big statistical sample that tries to average over all these different merging scenarios, and try to get a statistical idea of what dark matter is doing during these cosmological crashes."

During these incredibly large-scale mergers, scientists have observed that individual stars in these galaxies are so far apart that they very rarely run into one another. So, rather than creating a big, messy wreck, the stars sort of neatly fold together.

However, in between the galaxies is a thick gas full of charged particles. When the galaxy clusters collide, the gas splatters in all directions, like water splashed from a puddle, Harvey said.

"If we measure the dark matter [after the collision], and should it lie where the galaxies are, we know the dark matter is completely collisionless, and doesn't interact with itself at all," Harvey said. "And if it should lie where the gas is, we'd say that the dark matter is actually interacting with itself a lot, like a liquid."

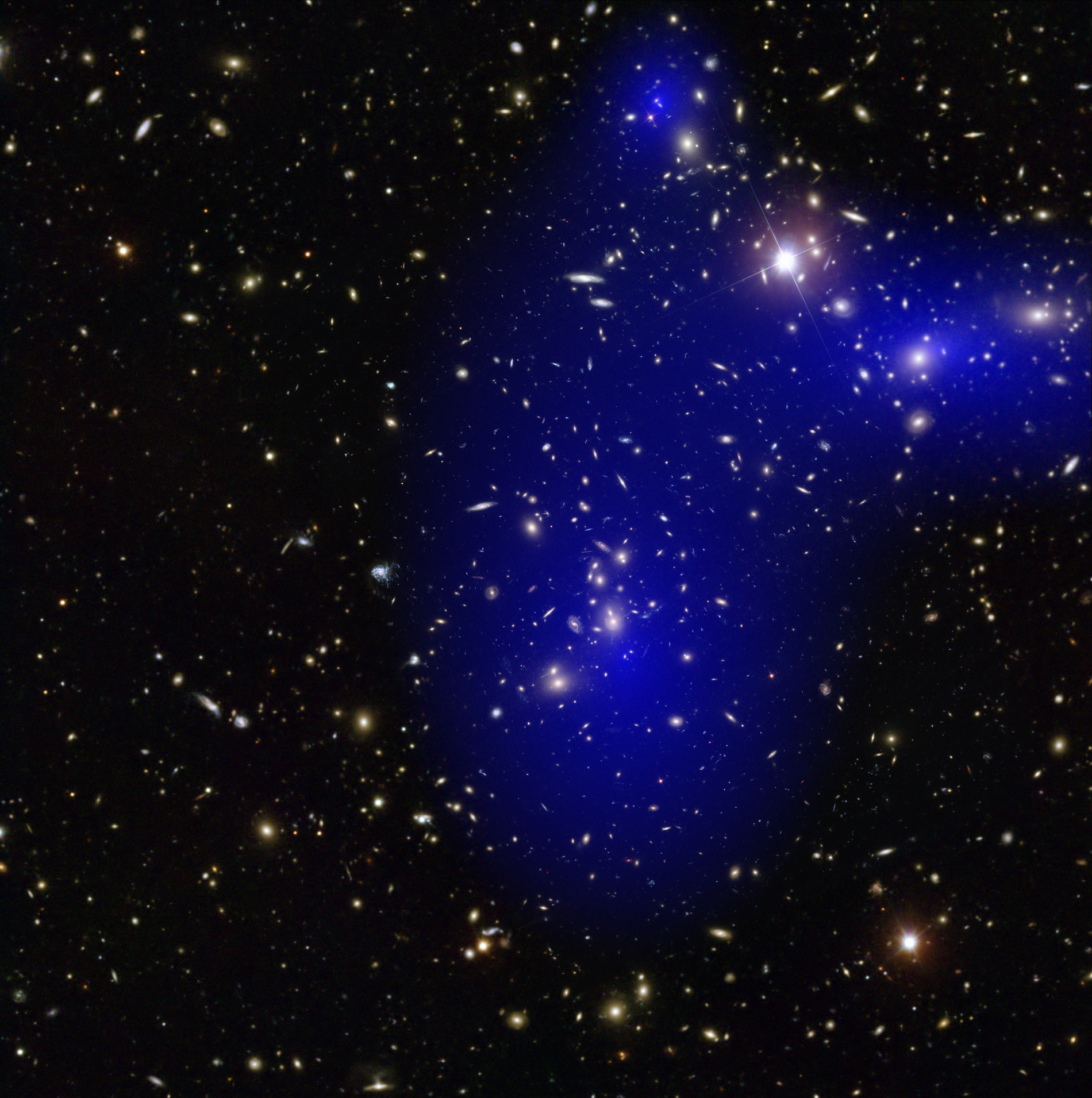

The researchers gathered data on a total of 30 galaxy-cluster collisions. In order to see the stars, the gas and the dark matter, they needed observations from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory. [Chandra Observatory's X-ray Universe in Photos]

Dark matter doesn't radiate or reflect light, but its gravitational pull can help scientists "see" it. Light that is passing near a very massive object will bend around it, in an effect called gravitational lensing. Scientists can see the bending of the light and use that to figure out where dark matter is present.

By looking at 30 galaxy-cluster mergers, the researchers showed that the dark matter behaves more like the stars: It doesn't splatter during these collisions, but instead remains largely unchanged by the merger.

The dark sector

The implications of the new finding go beyond galaxy mergers: They tell scientists something about what dark matter might be made of.

The gas that is found in between the galaxy clusters tends to splatter during collisions because it interacts with itself, the way a liquid does. Notice how liquids in microgravity tend to join together into bubbles — the material sticks together even though it isn't bound together like a solid.

Protons — the particles at the heart of every atom — interact with one another in a similar way. Harvey and his colleagues showed that dark matter clearly doesn't interact with itself the way the gas does; more specifically, it interacts with itself less than protons interact with one another.

Some theories of dark matter posit that it is part of a "dark sector" that is sort of like a mirror of the regular universe — in other words, that it contains dark versions of regular matter particles, like dark photons and dark electrons. In some of those theories, dark matter might be made up of dark protons.

"Chances are that dark matter is not made up of dark protons interacting with dark protons, and chances are, there is not a mirror universe out there with these dark particles," Harvey said. "The caveat is that theorists could change some of their parameters, so the field is still open to what [dark matter] could be, but we're narrowing it down."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter