Violent Methane Storms on Titan May Explain Strange Dunes

Rare tropical methane storms could help solve the mystery of how strange, giant dunes form on Titan, Saturn's largest moon, researchers say.

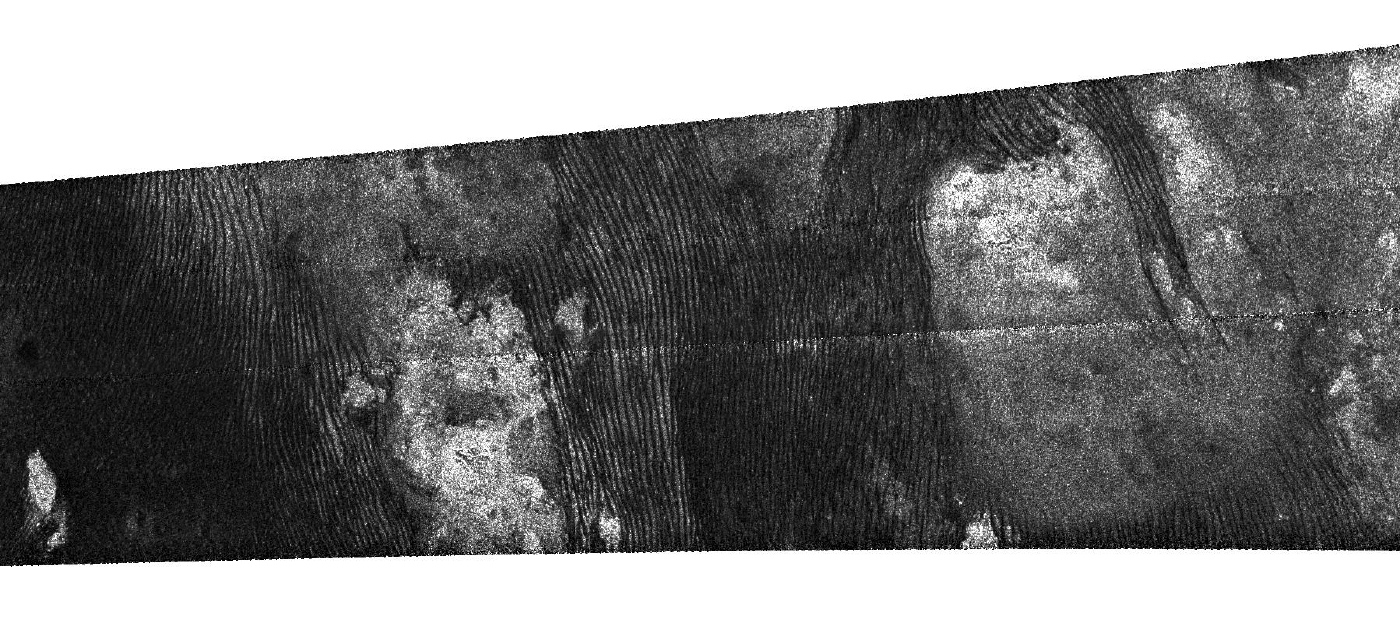

When NASA's Cassini spacecraft began exploring Titan in2004, its most dramatic discovery was the field of dunes that covers nearly 15 percent of Titan's surface along its equator. These dark, massive dunes — the largest of their kind in the solar system — are made of exotic sand composed of hydrogen and carbon. They can be more than 330 feet (100 meters) high and are typically 18 to 31 miles (30 to 50 kilometers) long.

These long, colossal dunes pose one of Titan's greatest mysteries, as they seem to grow eastward, whereas models of Titan's atmosphere predict that surface winds at its equatorial latitudes would blow westward. However, prior research found that Titan's winds do blow eastward at altitudes above about 3 miles (5 km). This finding has led scientists to wonder if these high winds might somehow help solve this puzzle, even though they blow far above these dunes. [Amazing Photos of Titan by NASA's Cassini]

Now, researchers have found that rare methane storms could help sculpt the moon's surface.

"Clouds and storms are rare on Titan," said Benjamin Charnay, a planetary scientist at the Dynamic Meteorology Laboratory in Paris and lead author of the study detailing the new findings. "They were not expected to have an impact on dunes."

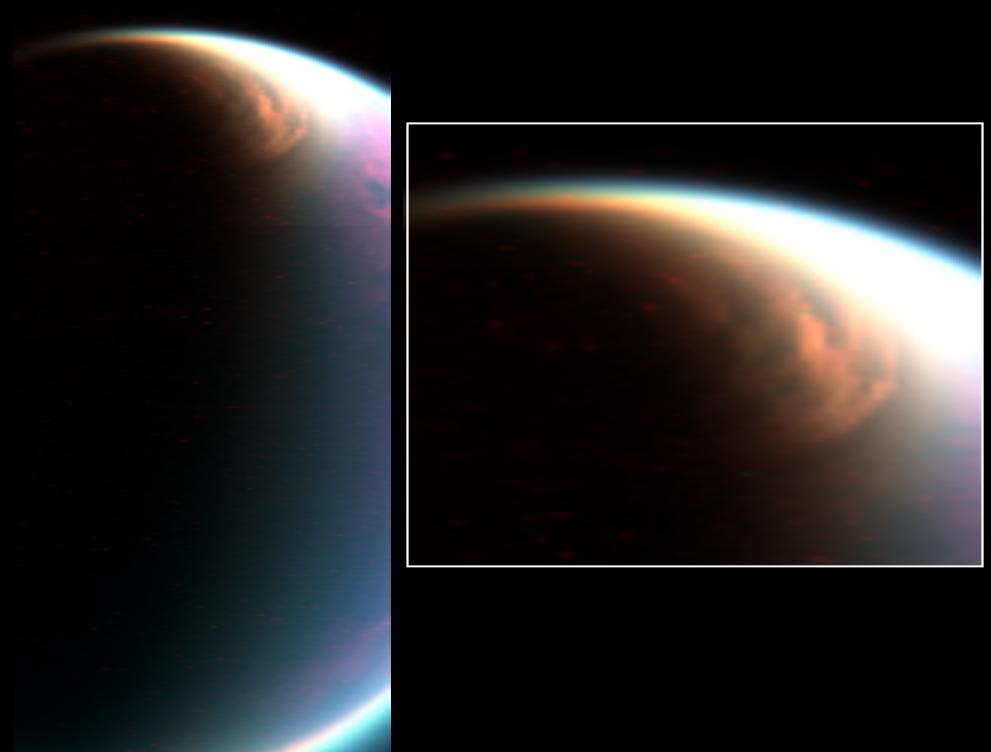

Titan is the only moon in the solar system with a thick atmosphere. Its atmosphere is composed mostly of nitrogen, with a trace of methane that can form into clouds. During the equinox, when days and nights are about the same length, Titan experiences huge, violent methane storms in the tropical regions around its equator.

Computer models of weather on Titan revealed that methane clouds can reach altitudes of 15.5 miles (25 kilometers), where the high, fast eastward winds blow. The researchers found that, as a result, methane storms can produce downdrafts that flow eastward on strong gusts after they reach Titan's surface.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers estimated that these eastward gusts can reach up to 22 mph (36 km/h) — 10 times faster than the usual winds close to Titan's surface.

"We were very surprised by the intensity of the storm gusts," Charnay said. "For Titan, it is like a hurricane."

The researchers suggested that these storm gusts may explain the shape, size, spacing and eastward growth of Titan's dunes. If scientists can get a better understanding of how these dunes form on Titan, it could reveal more insight into the moon's present and past atmosphere.

"There are long dunes on Titan which formed over a very long period of time, likely more than 1 million years," Charnay said. "Others are shorter and formed during the last 100,000 years."

By studying Titan's dunes, scientists can also learn more about dune formation on Earth. For example, in this new study, the researchers developed a new growth mechanism for dunes that may answer questions about how dunes form on Earth, Charnay said.

The scientists detailed their findings online April 13 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us