Hubble Telescope at 25: The Trials and Triumphs of a Space Icon

This week, the Hubble Space Telescope completes 25 years in orbit around Earth, and for much of that time, the telescope has sent home photographs that have wowed the world. But an entire generation has grown to adulthood with no memory of a time when the iconic instrument, whose highly anticipated first image was a colossal disappointment, was considered a national blunder.

Yet the Hubble Space Telescope overcame that obstacle and other challenges on its journey to capture the incredible images of the universe people around the world admire today.

The film "Hubble's Cosmic Journey," premiering tonight (April 20) at 10 p.m. EDT on the National Geographic Channel, features many of the men and women who worked with the telescope and helped it overcome its many challenges. [The Hubble Space Telescope at 25: A Photo Anniversary]

"Hubble was touted as the best thing for astronomy since Galileo pointed a telescope at the heavens," Jeff Hester, a NASA scientist and chief engineer who appears in the film, told Space.com at the film's world premiere. But "almost overnight, Hubble went from being a jewel in the crown of NASA astrophysics, the heir apparent, to a running joke," Hester said.

The Hubble telescope's journey from an embarrassing failure to a revolutionary science instrument is a story of inspiration and perseverance.

'A huge disaster'

The Hubble Space Telescope launched on April 24, 1990, and people from around the world awaited what was expected to be an incredible first image. Hester recalled the first light show that took place at Building 13 at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

"We got the first image, and they made a big deal of walking it over," he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The unveiling of the image was historic, but not for the anticipated reasons. The first photo from Hubble lacked the sharpnessthe world had hoped for.

"It was just not what we were expecting to see," Hester said.

Hester recalled Roger Lynds, an astronomer with the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, staring at the image, repeatedly rubbing his head.

Finally, Lynds announced, "The damn thing has spherical aberration."

It took many tests to confirm what Lynds had recognized that day. Spherical aberration meant that the focus of the most precisely ground mirror of the time was off by about 2,200 nanometers — 1/50 the width of a human hair. This tiny defect meant that the light reflecting from the edge of the telescope failed to meet up with the light reflecting from the center. [How the Hubble Space Telescope Works (Infographic)]

"For a great many things, the telescope was no more useful than a telescope on the ground," Hester said.

Among its fantastic science goals, Hubble was supposed to measure the expansion of the universe by studying stars known as Cepheid variables in other galaxies.

"There was no way in hell you were going to do photometry with Cepheid variables in Virgo using this aberrated telescope," Hester said. "It was a huge disaster."

The disappointment extended beyond the scientific community. Hubble had been highly anticipated by both the public and the media, and the resulting backlash was an added sting to the scientific loss.

"Jay Leno especially took us to task," Hester said. "He turned 'Hubble' into a verb."

It wasn't a good one — to "Hubble it" meant to seriously mess something up.

The 'camera that saved Hubble'

Hester said the solution came about in two ways. One involved the scientists who were stuck with a broken instrument.

"A bunch of people worked really hard to get science out of the space telescope as it was flown," he said. [The Hubble Telescope's Most Amazing Discoveries]

Although only 15 percent of the light collected by the telescope was usable, the scientists were still able to collect data from the instrument. This was enough to keep the momentum of the telescope going, ensuring that people didn't walk away from the project, Hester said.

Numerous solutions were presented to correct the space telescope's problems. Hester compared the problem to the relationship between his eyes and his glasses: Someone with perfect sight peering through his lenses would say they were ineffective, but the error in his glasses cancels out the problems in his eyes.

"With Hubble, you're stuck with the eyeglasses," Hester said. "You have to make new eyes."

Hubble's new eyes came in the form of two instruments, COSTAR and WFPC2. The telescope was designed to be modular, with instruments that could be removed and replaced over time. The more famous of those instruments was the Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement (COSTAR), a collection of movable mirrors that changed the light entering three of the scientific instruments, correcting for the faulty mirror focus.

But Ed Weiler, NASA's chief scientist for the Hubble telescope from 1979 to 1998, said it was not COSTAR that saved the instrument, but rather the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2), a scientific camera designed to precisely correct for the error in the shape of the main mirror. Indeed, WFPC2 was the "camera that saved Hubble," Weiler told Space.com.

"COSTAR was, at best, a 7 percent solution," Weiler said.

"I give it 10 percent," Hester interjected.

Astronauts installed the instruments during the first space shuttle servicing mission. Weiler remembers announcing that they had determined the cause of the imaging problem in 1990. "We have a way to fix it, and we'll do it by December 1993," he said at the time.

Hester, however, doubted that timeline. He approached John Trauger — the principal investigator of WFPC2 at the time— to ask what the real, not-for-the-cameras target date was.

Trauger stuck to his original answer. The result was a friendly bet for a bottle of Scotch that Hester had to pay for after the space shuttle carrying the two instruments into space launched at the beginning of December 1993. Astronauts attached COSTAR and WFPC2 to the orbiting space telescope, and Hubble began making the beautiful images it has since been known for.

"I was happy to lose," Hester said.

Evolving technology

"We never thought it would last 25 years," Weiler said. "It was built so it would last three years."

Over a 22-year period, astronauts have serviced the space telescopefive times. The last mission took place in spring 2009 and replaced the gyroscopes that provide stability, as well as other mechanical parts. [Fixing the Hubble Space Telescope: The Missions in Photos]

"Without the astronauts, Hubble would just be a piece of floating space junk," Weiler said.

Over a quarter of a century, the telescope itself hasn't really changed. What has changed, however, are the scientific instruments it carries. The original plans called for modular Hubble scientific instruments that could be removed to allow for new components to be installed.

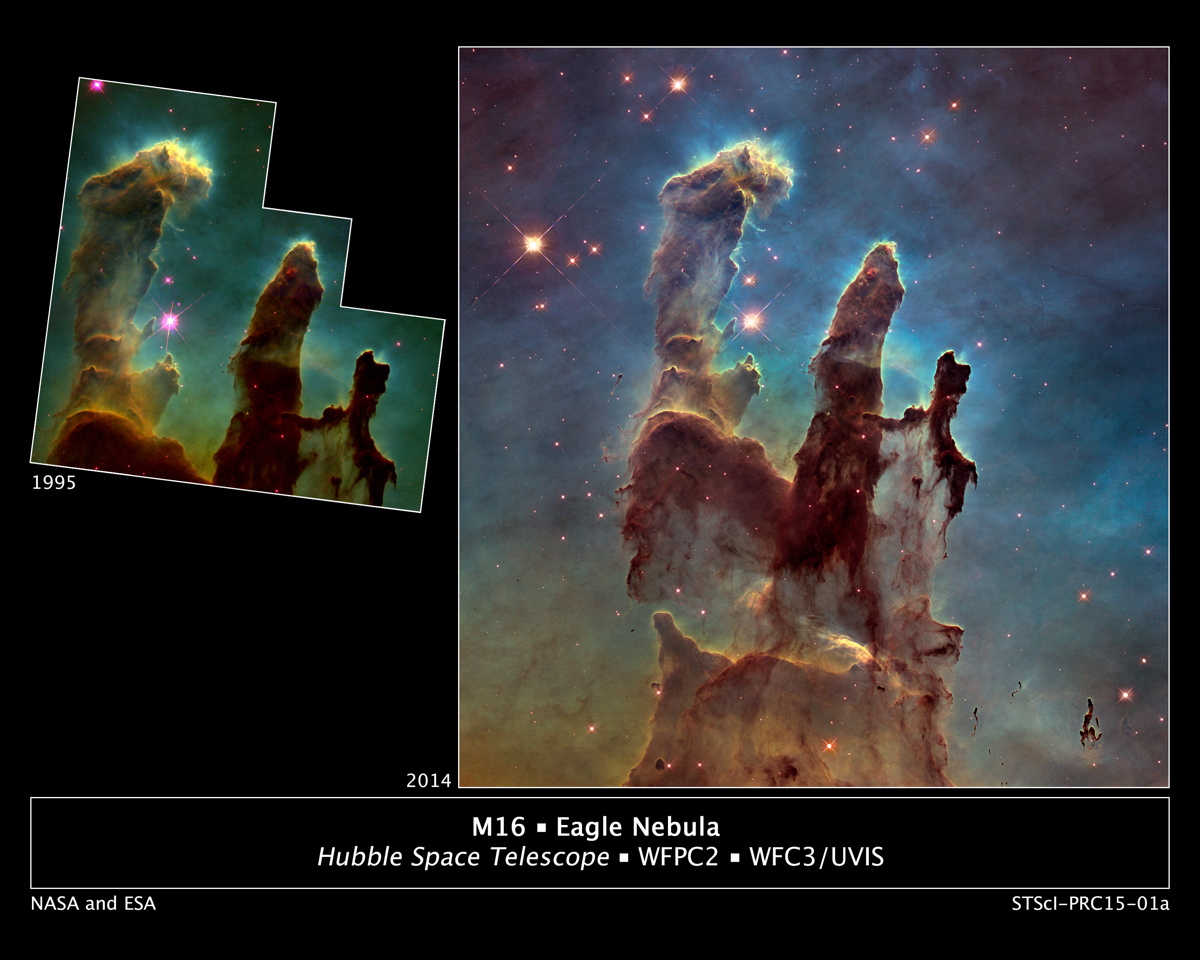

The Advanced Camera for Surveys — the last of the original instruments — was replaced in 2002, eliminating the need for COSTAR. The camera that saved Hubble was removed in 2009 and was replaced with its successor, the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 3; the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph was installed at the same time. These instruments have allowed the data from the Hubble telescope to evolve and improveas technology has advanced over the years.

"The increase in the technological capacity of its instruments has really made a big difference," Weiler said.

These upgrades have kept the Hubble Space Telescope at the forefront of science, constantly expanding humans' understanding of the universe, and making it one of NASA's greatest science missions.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd