The Last Hubble Servicing Mission: Q&A with Photographer Michael Soluri

The Hubble Space Telescope has been transforming our view of the cosmos for 25 years, thanks in part to the efforts of some spacewalking astronauts.

Hubble launched aboard the space shuttle Discovery on April 24, 1990. It soon became apparent that something was seriously wrong: The instrument returned blurry images, and engineers determined that a flaw in Hubble's main mirror was to blame.

Astronauts fixed the problem during a 1993 mission to Hubble, then repaired or upgraded the iconic observatory on four additional servicing missions, the last of which occurred in May 2009. Michael Soluri chronicled the leadup to that last mission, gaining unprecedented access for a non-NASA photographer and shedding light on the people behind that unique time in history. [Michael Soluri Discusses Last Hubble Servicing Mission (Video)]

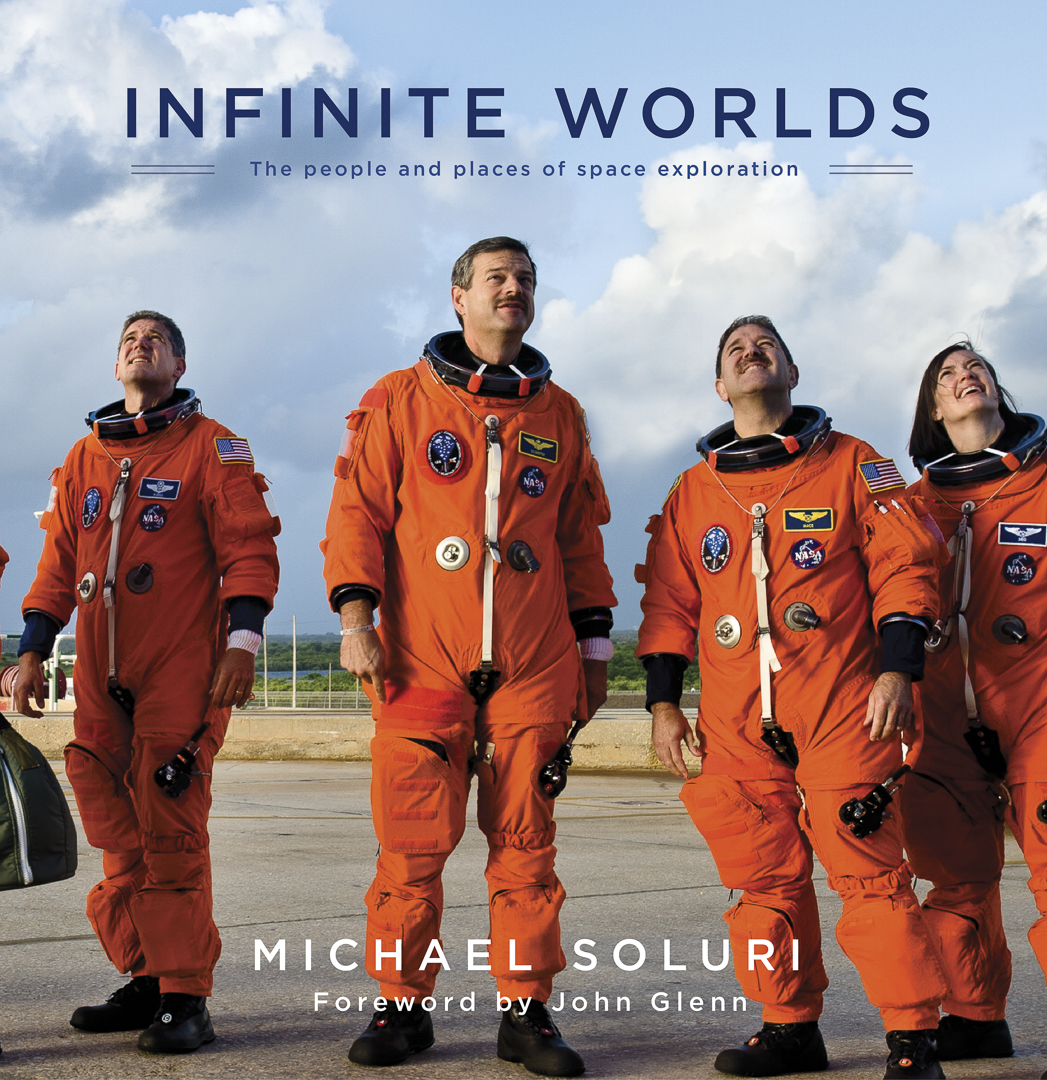

Soluri stopped by Space.com's office last week to chat about that project and his recently published book, "Infinite Worlds: The People and Places of Space Exploration" (Simon & Schuster, 2014). Here's our conversation.

Space.com: What drew you to Hubble in the first place?

Michael Soluri: What drew me was the very notion that historically this was going to be it. Two events were happening simultaneously. The [space] shuttle program was going to come to an end. And this was going to be the last human spaceflight to the telescope. I really felt that, with all due respect to the space station assembly, there was something about Hubble, at that point in its nearly 20-year history, that compelled me to realize this was historic. [See more photos from the final Hubble mission by Michael Soluri]

Space.com: So why document it in this way?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Soluri: I'm a fine-art documentary photographer. And editorial has been my livelihood all my career. And I felt that a photographic story that connects with the people — not just the hardware — but with the people [was essential].

It was an uphill battle, because I wanted to get the crew — that's always very challenging — and the folks, the engineers, to put a human face to this thing. Corey Powell, who was the executive editor at Discover magazine, was very set with the idea. And so the genesis for the entire project was launched within 15 days of the announcement [that the fifth servicing mission would take place]. That was October 2006. We had our meetings in November of 2006. By February 2007, I was down in Houston meeting [astronauts] John Grunsfeld and Mike Massimino, presenting myself and my work — what my goal was — and from there it was all history.

Space.com: Was it hard to get your foot in the door?

Soluri: Access to anything in the American space program — in any space program — is very challenging because there are restrictions for all the obvious reasons. And so in this case I had a lot of friends who worked the news side of [NASA's] Kennedy Space Center and always said, "Michael, if you really want to do something beyond the velvet ropes — the scripted events that NASA provides — you're going to need to have a crew signoff. It's possible."

So on that message, I went down and made the pitch, realizing if I had done the other route we would have just been in a queue. I would have just attended scripted events, and I've done enough of that in my life. I wanted to get something that was extraordinary that could never be repeated. And John [Grunsfeld] and Scott Altman, the [space shuttle] commander, were very receptive. And Mike Massimino had a good part in this too. And the result was a portrait session, and that opened up all the doors.

Space.com: Walk me through pre-launch. What were you doing then?

Soluri: My involvement began two years out from launch. I got to really begin to understand the scope of the training, and at the same time I got to go back repeated times to the same place. So I could discover the unknown. And so with my access, I got to explore different kind of lighting scenarios, the people, so to the point where basically, "It's Michael." I mean they could trust me. That was a really big piece. [The Hubble Space Telescope: A 25th Anniversary Photo Celebration]

I asked Mike Massimino early on, I said, "What's the quality of light like in space?" And he stopped, and he said to me, "Could you help the crew and I make better pictures in space?" And I said, "But you have all the technical stuff. You have more equipment than I'll ever get in my lifetime." But he said, "No, we want to be able to feel it, see it better." So I said, "Yeah, I can teach you how to do that."

So I spent three sessions before flight working with them, making them aware of the environment that they can respond to, what qualities of light, objects, and things like that to make it more meaningful. And so between that and the experiences of being with the engineers, having access to the EVA [extra-vehicular activity] tools, when it led up to launch day, Scooter [Scott Altman] and I had a meeting with Steve Lindsey, who was the chief of the astronaut office at the time, and made our pitch. Scooter made the pitch — why I should be with them in the room four hours before they go to the pad — and Steve approved that. And that was very special. I photographed it all in black and white. I couldn't have done it any other way. It was that sublime.

And I had to keep in the back that these are my friends and they're going to go up in that thing. You could hear the ventilating system, and there was some joking around, but there was a seriousness. And it was a ritual, which I was fascinated in. It was the same ritual in that room that's been going on since Apollo. It was the same one that Neil Armstrong left in. So it was like, "Wow, look at where I am." And that lasted for 10 seconds, then it was, "You have an hour to do this." And that was memorable.

Space.com: Was that your most memorable moment?

Soluri: Oh, there were many. There were moments in the high bay, which is the dust-free room at [NASA's] Goddard Space Flight Center [in Maryland], where I was photographing the tools, and heads would turn because they gave me permission to photograph these space tools, these one-of-a-kind pieces of sculpture to me. And all my equipment had to be cleaned down; I'm wearing the bunny suit, the gloves, the whole works. It wasn't Hugo Boss. And heads turned, and I continued.

Space.com: How did you train the astronauts in photography? And then how did their pictures turn out while they were servicing Hubble?

Soluri: Apollo crews that I got to meet always told me in retrospect that they wish they had more time to smell the roses. I wanted to convey that to this crew. Of the seven, four rookies were going up for the first time.

So the goal was to be aware. Even if you don't make pictures, become aware of it.

Space.com: You said smell the roses, but at the same time, this particular mission almost didn't happen. So I can image there was a lot of pressure on the astronauts at the time. What was the atmosphere like?

Soluri: They were originally supposed to go up in October 2008. And 20 days before that launch, everybody was ready. I could see it in their eyes. They had launch fever, they called it. The backup computer system on Hubble broke. It just simply stopped functioning. And that was on a Sunday. And by Monday morning, they said we're off. NASA agreed to reschedule the mission. That bought an additional seven months. And I think that's when I really saw everybody come together really tight. And I think the mission was as successful as it was because of that extra seven months.

Space.com: So how did you get that across in terms of the layout of your book?

Soluri: I made about 12,000 pictures. It took about a year for me to come down from the project because this was all I did. It was very intense. And to make sense of what I did. And it took another two years to begin figuring out what the patterns were and where the story was. And my agent was ready to go out and sell the book. [Photos: NASA's Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Missions]

I had a moment where something came together to help me figure out the story. … [it] was a sense of time and distance. Hubble captures ancient light. And I realized, Well, the way to get into the story, to show people on Earth, is to give a sense of what the telescope does out in space. It's all relative to what I call "waterworld Earth." And it's humbling because you realize we're on this little water world in the solar system with a star that's on this spur of the Orion spiral in a galaxy. That's it. We're fixing this little tiny telescope to reach deep back and understand the universe. So it was that sense of scale.

And I think what really set it off was [when] David Leckrone, who was project scientist for Hubble, sent me a photograph that Hubble took of Omega Centauri, a globular cluster of stars. It's 15,000 light-years away. I thought about that 15,000 light-years. So the light left 15,000 years ago. That's the time when our ancestors were drawing animals on the caves of Lascaux in France. So that's Earth and that was happening in space — so I found that connection, and that resulted in the prologue to the book. And I think that gave me a deeper sense of the narrative and the purpose. And then I found the groove.

Space.com: So you have stories throughout your book from particular crewmembers and others. Do you have a particular story that really stands out to you?

Soluri: They all stand out to me. I chose weaving what I call "first-person stories" of 18 people, four of the crew, and others that were representative of the Hubble team and the shuttle team, to get a sense in their words what it was like behind the scenes. The way I placed them in the book, it moved the chronology and the narrative of the story. So it explained what they were doing and why, without me having to explain it. So they were telling it in their own words, unscripted.

Space.com: I loved [astronaut instructor] Christy Hansen's story.

Soluri: Christy was great. I was impressed with her from the moment I met her and saw her work with the crew — her level of energy, and she knew what she was talking about. I thought, "How could somebody know so much?" And the crew was just glued to her. And of course what she was doing was figuring out the choreography, essentially writing the script that they would be using up in space. And I think she was also a very motivating story for other young women to come into a profession that has typically been the "guy thing." And I think she explains why that glass ceiling is no longer glass. [Inside Hubble's Universe (Video Show)]

Space.com: So tell me about the flame trench.

Soluri: So when I was doing the research on the cave walls, I discovered through this thermodynamics engineer that there's this whole other world under the launch pad. And that's where all the flames come in. We just see the white — it looks like smoke, but it's water vapor, essentially — steam. The purpose of all the water is to abate the sound, so the sound doesn't come up and destroy the rocket as it's ascending, and [it] also just cools things down. The markings they left [on the flame trench] were beautiful. And after each launch, technicians would go in there and they'd mark them up with circles, rectangles and squares. It was like a cave wall. And to me, what I realized was: This is the evidence of space flight on Earth. The shuttle as a machine left its mark.

This thing was enormous. It must have been 80, 90 feet high and at least 300 feet long. And it was like going into a cave. And the launch pad would sit over it. And you go along, you can still see evidence of the Saturn launches from the Apollo era. Because Saturn burned kerosene, it was jet-black. I felt that that grounded it. It became every bit of important, to me at least, as discovering a cave painting, or a drawing by our ancestors.

Space.com: So how is spaceflight changing? Is it going to be harder to document missions in this way? Is it even going to be possible?

Soluri: I don't know. I hope I've laid the groundwork that it's possible to get behind the scenes and document something that will be gone. Apollo didn't do this. Nobody in that era thought about this. And so like the signature wall at the Vertical Assembly Building — that's the cathedral-like building where the rockets are all put together [at Kennedy Space Center] — 7,300 people came and signed their name. And that they were a part of this thing and it meant something. That will be there as long as that building is standing.

It's a lot of work. You have a different generation coming in. My hope is that this sets a precedent for those managers and for crews, particularly with SLS [NASA's Space Launch System megarocket] coming on board — if we end up going back to the moon, let's say, that there'd be some interface and some kind of unique documentation. But this was unique. This was unique.

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Shannon Hall is an award-winning freelance science journalist, who specializes in writing about astronomy, geology and the environment. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Nature, Quanta and elsewhere. A constant nomad, she has lived in a Buddhist temple in Thailand, slept under the stars in the Sahara and reported several stories aboard an icebreaker near the North Pole.