A NASA spacecraft slammed into the surface of Mercury on Thursday (April 30), bringing a groundbreaking mission to a dramatic end.

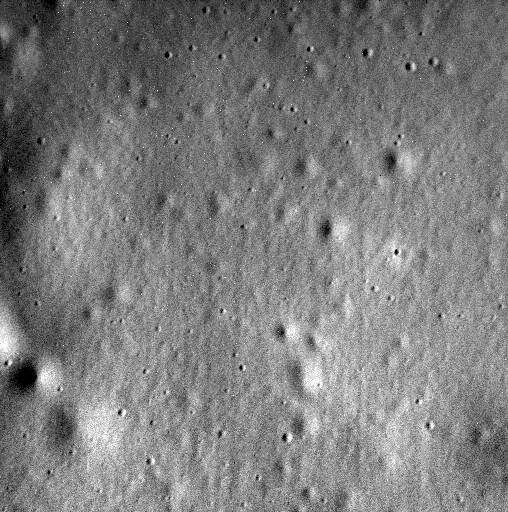

The MESSENGER probe crashed at 3:26 p.m. EDT (1926 GMT) Thursday, gouging a new crater into Mercury's heavily pockmarked surface. This violent demise was inevitable for MESSENGER, which had been orbiting Mercury since March 2011 and had run out of fuel.

The 10-foot-wide (3 meters) spacecraft was traveling about 8,750 mph (14,080 km/h) at the time of impact, and it likely created a smoking hole in the ground about 52 feet (16 m) wide in Mercury's northern terrain, NASA officials said. No observers or instruments witnessed today's crash, which occurred on the opposite side of Mercury from Earth. [Last Mercury Photos from NASA's MESSENGER]

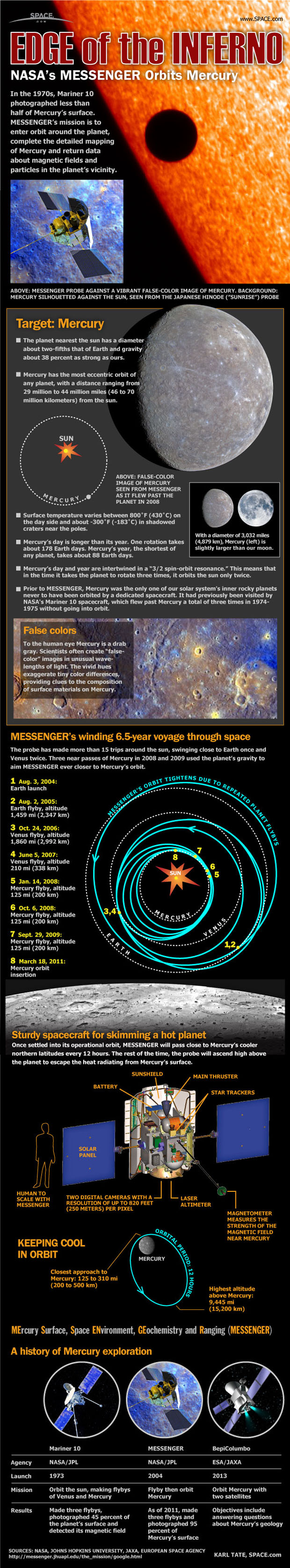

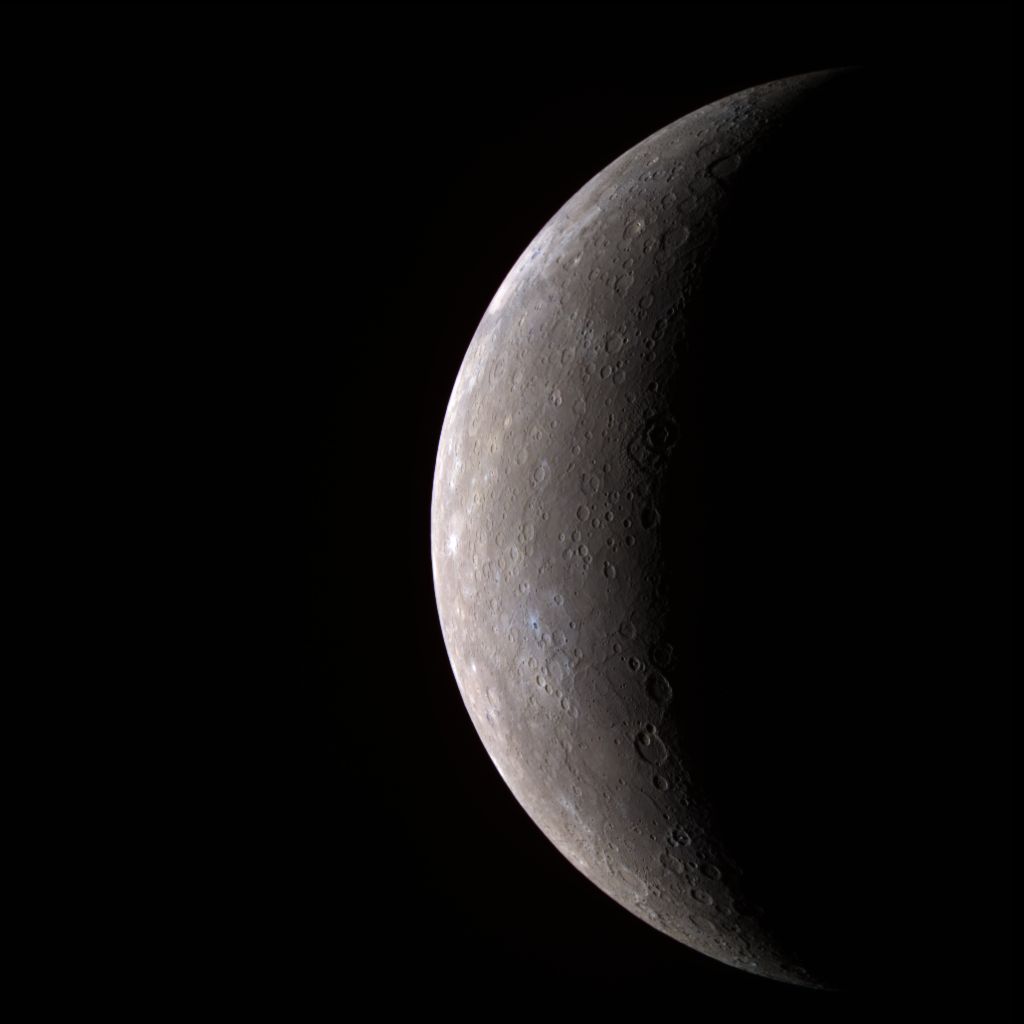

MESSENGER was the first spacecraft ever to orbit the solar system's innermost planet, and its observations over the last four years helped lift the veil on mysterious Mercury, mission team members said.

"Although Mercury is one of Earth's nearest planetary neighbors, astonishingly little was known when we set out," MESSENGER principal investigator Sean Solomon, director of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, said in a statement.

"MESSENGER has at last brought Mercury up to the level of understanding of its sister planets in the inner solar system," Solomon added. "Of course, the more we learn, the more new questions we can ask, and there are ample reasons to return to Mercury with new missions."

Confirmation of MESSENGER's death came at 3:40 p.m. EDT (1940 GMT), when NASA's Deep Space Network station in Goldstone, California, was unable to detect a signal from the spacecraft, NASA officials said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"On behalf of MESSENGER, thank you all for your support. We will continue to update you on our great discoveries. We will miss it," mission team members tweeted Thursday, via the @MESSENGER2011 account.

Bringing Mercury into focus

The $450 million MESSENGER spacecraft, whose name is short for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging, launched on Aug. 3, 2004.

The probe took a long and looping trip through the inner solar system, relying on flybys of Earth, Venus and Mercury to slow down enough to be captured by Mercury's gravity. (Mercury lies very close to the sun, whose powerful gravitational pull would accelerate to great speeds spacecraft taking a direct route to the planet.)

MESSENGER finally arrived at Mercury on March 17, 2011, becoming the first probe ever to orbit the heat-blasted world, and just the second spacecraft ever to study it up close. (NASA's Mariner 10 probe performed three Mercury flybys in 1974 and 1975.)

MESSENGER's original mission at Mercury was supposed to last just one year, but NASA extended operations twice so the probe could continue its observations, which team members say have revolutionized our understanding of the planet.

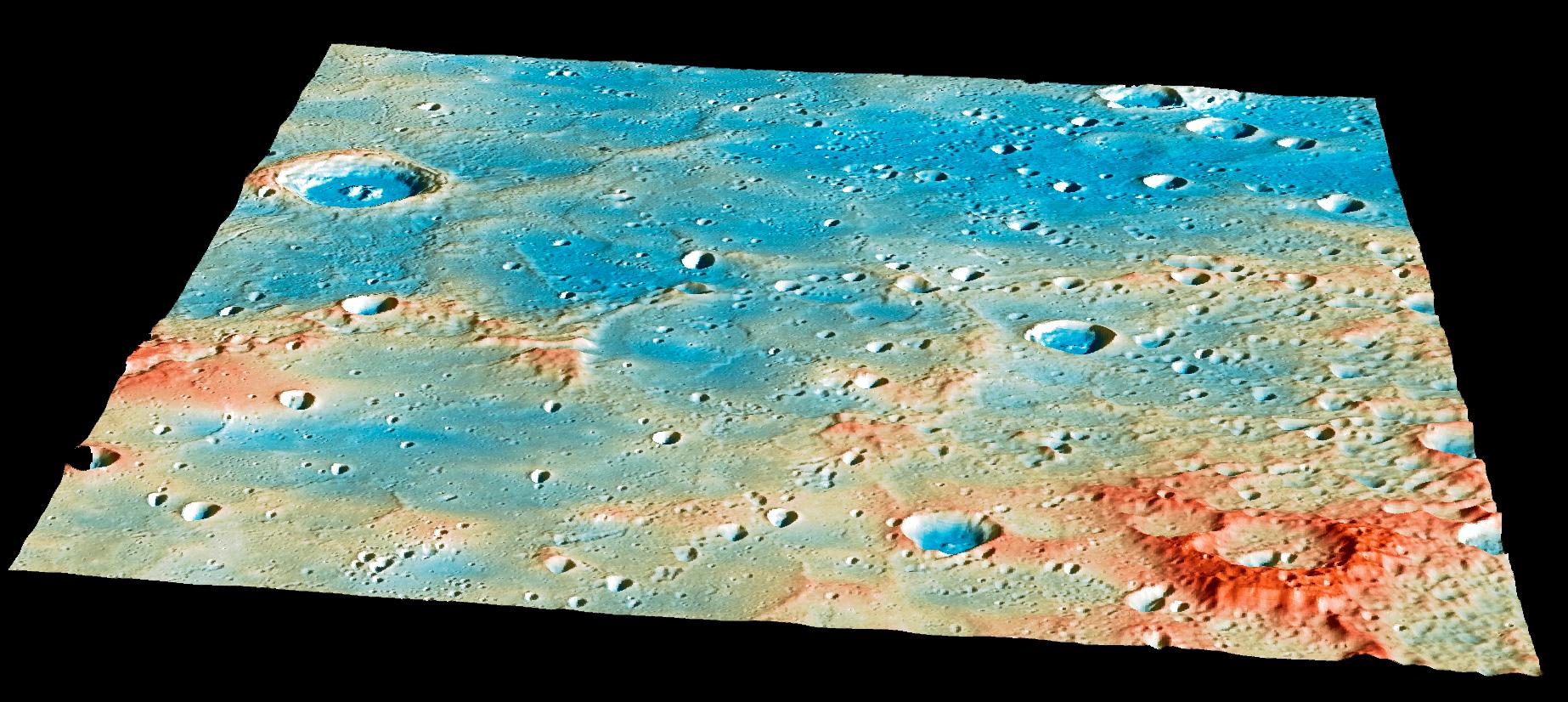

For example, MESSENGER mapped the planet in unprecedented detail, discovered that Mercury hosts a strangely offset magnetic field and confirmed that permanently shadowed craters near Mercury's poles harbor deposits of water ice.

"The water now stored in ice deposits in the permanently shadowed floors of impact craters at Mercury's poles most likely was delivered to the innermost planet by the impacts of comets and volatile-rich asteroids," Solomon said. "By this interpretation, Mercury's polar regions serve as a witness plate to the delivery to the inner solar system of water and organic compounds from the outer solar system, a process that much earlier may have led to prebiotic chemical synthesis and the origin of life on Earth."

During the course of its four years at Mercury, MESSENGER captured more than 250,000 images and used its seven scientific instruments to gather extensive data sets that will keep scientists busy for years to come, NASA officials said.

The mission also leaves a technological legacy that could help future spacecraft work in harsh environments, officials added. For instance, MESSENGER's ceramic-cloth sunshade effectively protected the probe's instruments against powerful solar radiation.

"The front side of the sunshade routinely experience[d] temperatures in excess of 300 degrees Celsius (570 degrees Fahrenheit), whereas the majority of components in its shadow routinely operate[d] near room temperature (20 degrees Celsius or 68 degrees Fahrenheit)," MESSENGER project manager Helene Winters, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, said in the same statement.

Next probe up

MESSENGER blazed a trail that another spacecraft will be following soon: The joint European-Japanese BepiColombo mission is scheduled to launch in 2017 and arrive in orbit around Mercury in 2024.

BepiColombo consists of two different orbiters. One of them will study Mercury's surface and internal composition, and the other will focus on the planet's magnetosphere.

During the course of its work, BepiColombo may identify and investigate MESSENGER's grave, in an attempt to better understand how space weathering affects Mercury's surface, Solomon said.

The BepiColombo team "will be looking for signs of [MESSENGER's] crater, and if they can make measurements of it, they will know precisely how long that region has been exposed to space," Solomon said during a news briefing earlier this month. "That will be an important study that comes a decade from now."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.