Gravitational 'Slingshot' May Have Flung Runaway Galaxies Far, Far Away

Rare loner galaxies millions of light-years away from any neighbors may be runaways from violent, disruptive relationships with other galaxies, researchers say.

Runaway objects are common in space. Astronomers think there are billions of runaway planets in the Milky Way — rogue worlds not gravitationally bound to any star. Moreover, scientists know of about two dozen runaway stars that escaped from the Milky Way at high speeds, and even one runaway cluster of about a million stars that fled the giant galaxy Messier 87 about 53.5 million light-years from Earth.

Now, researchers have discovered what appear to be 11 runaway galaxies. [Top 10 Strangest Things in Space]

"These small galaxies face a lonely future, exiled from galaxy clusters they were formed [in] and used to live in," study lead author Igor Chilingarian, an astronomer at both the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Moscow State University,said in a statement.

The scientists focused on rare galaxies known as compact ellipticals. These galaxies resemble the centers of regular oval-shaped elliptical galaxies. Theyare only a few hundred light-years in diameter; for comparison, the Milky Way is about 100,000 light-years across. Moreover, compact ellipticals are equal in weight to about a billion suns, making them about 100 times less massive than the Milky Way.

Prior research had found only about 30 compact ellipticals, such as Messier 32, which orbits the nearby Andromeda galaxy. These compact ellipticals were found mostly near giant galaxies in the centers of large clusters of galaxies. Computer models suggested these compact ellipticals might be the remnants of larger galaxies that had most of their stars stripped away from them by the gravitational attraction of neighboring galaxies, until they were only about a hundredth of their original mass.

However, previous studies found two compact ellipticals that were far away from any massive galaxy, raising the question of how they might have formed without larger partners to mooch off their material.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We asked ourselves how we could explain them," Chilingarian said in a statement.

To find out more about such isolated compact ellipticals, researchers mined a huge amount of astronomical data publicly available due to the Virtual Observatory initiative, including data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and NASA's GALEX spacecraft.

"The data and steps to reproduce our discovery are available not only for any researcher but for any Internet user, even without a registration required," study co-author Ivan Zolotukhin, an astronomer at both the Research Institute for Astrophysics and Planetary Science in Toulouse, France, and Moscow State University, told Space.com. "This is clearly a success of the Virtual Observatory initiative, which aims at making all astronomical data accessible in a convenient, standardized format without too much low-level hassle."

In addition to the 30 compact ellipticals detailed in previous studies, researchers have now discovered 195 more compact ellipticals.

"We didn't really expect to find that many compact elliptical galaxies because we still thought they were rare," Chilingarian told Space.com. [Gallery: 65 All-Time Great Galaxy Images]

Isolated galaxies

The scientists looked for compact ellipticals not only within clusters and groups of galaxies, but also between them. As the researchers expected, most of these compact ellipticals were found inside massive clusters and groups of galaxies. However, 11 were isolated, located millions of light-years from their nearest clusters.

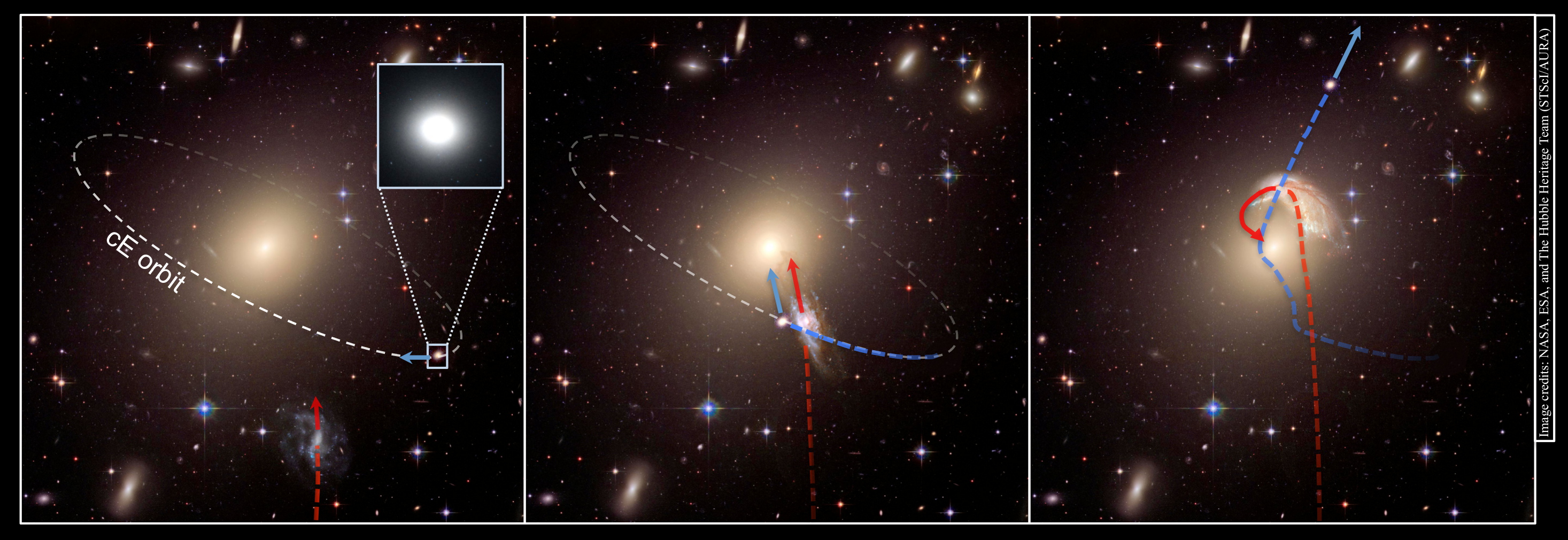

Runaway planets and stars were thrown away from their homes by gravitational interactions, and the scientists think these runaway galaxies were formed the same way. The researchers suggested that the compact ellipticals were victims of galactic threesomes — a massive galaxy initially tore away their outer parts, leaving only their cores, and later, some other galaxy flung these cores away. Similar activity is known to happen near the center of the Milky Way — a supermassive black hole can hurl away one of two stars in a binary system that came too close to it, and swallow the other star.

"This is the same phenomenon but working on a different scale —a slingshot effect —when, during a three-body encounter, the lightest body flies away from the system," Zolotukhin said in a statement.

"This is so far the largest scale on which a gravitational slingshot effect has been demonstrated to work," Chilingarian said.

The researchers analyzed the velocities of compact ellipticals in galaxy clusters and found that many were on the verge of running away themselves. To escape the Earth, a cosmic body must travel faster than 24,600 mph (39,600 km/h), and to escape the solar system from Earth's orbit, an object must travel more than 93,950 mph (151,200 km/h). But for a compact elliptical to escape its cluster, it would have to travel about 5.6 million mph (9 million km/h), the researchers calculated.

Although compact ellipticals may face a future of solitude in the void of intergalactic space, if they stayed in their home clusters, they would probably get devoured by their massive neighbors in about a billion years, the researchers added. Life might actually be surprisingly calm on such disrupted galaxies, Chilingarian said.

"If there are planetary systems in the central region that remained in the galaxy after the tidal stripping event, there will be virtually nothing happening," Chilingarian said. Any stars in these compact ellipticals will likely be packed closely together, so "the sky on such a planet will be full of stars comparable to Venus by brightness. But since all these stars are old, there will be no risk of destructive events such as close supernova explosions," he added.

Any stars in the skies of such worlds likely would be older, and thus bright yellow or bright red, Zolotukhin noted.

Next, the researchers hope to use the 6.5-meter (21 feet) Magellan telescope in Chile to study the dark matter within these compact ellipticals. These galaxies should have had much of their dark matter stripped from them, which could influence their structure and evolution, since dark matter's gravitational pull helps keep many galaxies stable.

"We know that we shouldn't find any dark matter in them, so if we find some, it will be surprising and will call for explanations," Chilingarian said.

Chilingarian and Zolotukhindetailed their findings online April 23 in the journal Science.

Find more articles from Charles Q Choi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us