SpaceX Dragon 'Pad Abort' Latest in Line of Launch Escape System Trials

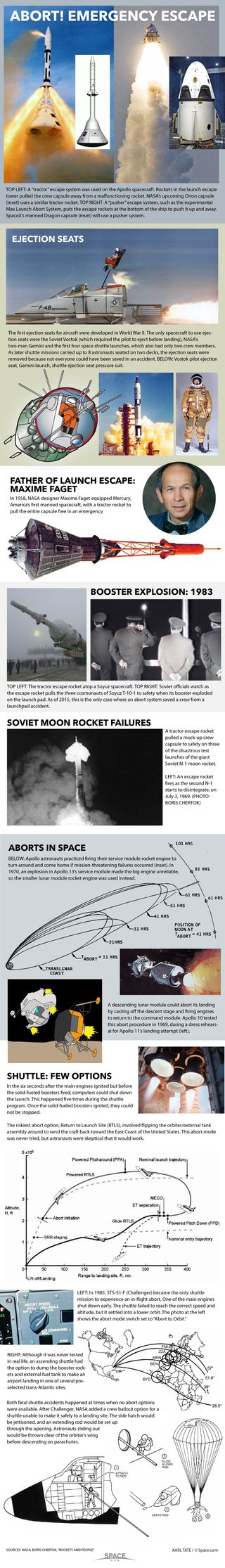

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — Before Alan Shepard lifted off to become the first U.S. astronaut in space 54 years ago on Tuesday (May 5), a trio of "pad abort tests" made sure his Mercury capsule could be jettisoned if the Redstone rocket he was riding failed.

Now, SpaceX is building off that history by staging its own pad abort test to prove that its innovative take on a launch escape system works as designed. The abort test comes two years before NASA astronauts are slated to launch on SpaceX's Dragon capsule under a contract with NASA.

(Boeing has also been selected to fly NASA astronauts on its CST-100 capsule and has announced plans for its own pad abort test in 2017.)

SpaceX is set to conduct the test on Wednesday (May 6) from Launch Complex 40 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. [SpaceX's Dragon Pad Abort Test in Pictures]

"It's our first big test on the crew Dragon," SpaceX's Hans Koenigsmann, vice president for mission assurance, told reporters last week.

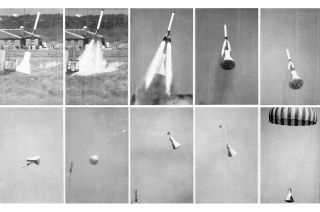

Unlike the Mercury tests on which the Dragon pad abort is modeled, SpaceX's capsule won't be pulled by a thruster-equipped tower mounted above the spacecraft. Rather, the Dragon's own downward directed engines will push it away from the rocket, or in this case, from a specially-designed mount standing in for the company's Falcon 9 booster.

If all goes as expected, the Dragon will fire its eight 3D-printed SuperDraco engines for six seconds, propelling it – and its dummy crew member on board — up to 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) before the capsule deploys parachutes and splashes down in the ocean.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

55 years in the making

Dragon's pad abort is the first to be conducted out of Cape Canaveral. The first such tests left the ground from further up the United States' East Coast.

Fifty-five years ago, a mockup of the Mercury spacecraft, called a "boilerplate," was mated with a production version of the launch escape tower — a 17-foot-tall (5.2 m) metal lattice painted red and equipped with several solid rocket motors — at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. On July 22, 1959, the escape tower's engines fired, pulling the mock capsule off an angled pedestal on the beach in what was the first operational test of such a system.

A second pad — or more accurately, beach — abort was carried out five days later. This time, the boilerplate was instrumented to obtain measurements of the vibration and sound environment encountered by the capsule during the firing of the tower's rockets.

The third abort test took off on May 9, 1960, with the first of McDonnell's production Mercury spacecraft. The flight, which lasted one minute and 16 seconds, was deemed a success, although the capsule was too close as the tower jettisoned.

These tests led to more advanced "in-flight aborts," where the capsule was mounted on top of a Little Joe rocket and launched into the atmosphere to test the escape system while under the stresses experienced during an ascent to space. SpaceX will also conduct an in-flight abort test as early as this summer, depending on the results of the pad abort test.

Between then and now

After Mercury and before Dragon, three other spacecraft took part in pad abort tests.

On the morning of Nov. 7, 1963, Apollo boilerplate 6 (BP-6) left the ground from the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, on the first test of the escape system that would protect the astronauts launching on the moon bound Saturn rockets. The 33-foot-long tower, powered by three solid-fuel rocket motors, sent the space capsule on a two-minute and 45 second flight that ended with it descending under parachutes to a relatively soft touch down.

The only problem reported was that the escape system's rockets had deposited soot on the sides of the spacecraft.

A second Apollo pad abort employed a boilerplate (23A) that had already flown on an in-flight Little Joe II abort test in 1964. Refurbished, it flew again on June 29, 1965, lifting off on a one minute, 52 second flight that peaked at 1.75 miles (2.8 kilometers) high.

This time, the abort systems' motors left no soot on the capsule's simulated window samples; only an oily film that was deemed not to be an issue. Pad Abort-2 was declared a success.

One more similar test occurred at White Sands, 45 years later. NASA returned to the site of its past Apollo trials to demonstrate the launch escape system for its Orion crew module. NASA and Lockheed Martin are building the Orion to take astronauts beyond Earth orbit, to the vicinity of the moon, an asteroid and ultimately on the journey to Mars.

An Orion boilerplate, larger than its Apollo predecessors, lifted off from the desert floor to about 1.2 miles high (1.9 km) propelled by a 45-foot-long (14 m) abort system tower. The flight took place on May 6, 2010, five years to the day before SpaceX's scheduled Dragon pad abort test.

Most recently, on Oct. 22, 2012, Blue Origin conducted its own pad abort using a pusher launch escape system akin to what SpaceX is now testing. Conducted under a NASA partnership and designed to support the company's private suborbital New Shepard spacecraft, the pad abort pushed a full-scale crew capsule 2,307 feet (703 m) above west Texas.

Click through to collectSPACE.com to see more photographs of historic pad abort tests.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2014 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.