Missing Asteroids Reveal Planet-Sized Mystery

Missingasteroids in our solar system may be the handiwork of rampaging giant planetsas they migrated to their current positions, according to a new computersimulation.

Scientistshave known that planets suchas Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune migrated during the first severalmillion years of early existence. The new simulation showed that the giant planetswould have disturbed many asteroids as they fled the scene, leaving behind"footprints" that match the real-life patterns in the main asteroidbelt.

"Itreally showed evidence that the footprints of planet migration are visibletoday in asteroid distribution," said David Minton, a planetary sciencesresearcher at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Patternsof planet migration

Previousevidence has suggested that the giant planets once formed a more compacthuddle. But their gravitational interactions with the then-larger Kuiper Belt,an icy region beyond Neptune filled with comet-likebodies, ended up fueling a migration.

"Eachtime the planets tossed these Kuiper Belt objects around, they would move alittle," Minton told SPACE.com.

Jupiterended up moving slightly closer to the sun, while the other giant planets movedfarther apart from both the sun and each other. Minton and Renu Malhotra,another planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, wanted to examine possibleaftereffects of that unstable period.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Gapsas evidence

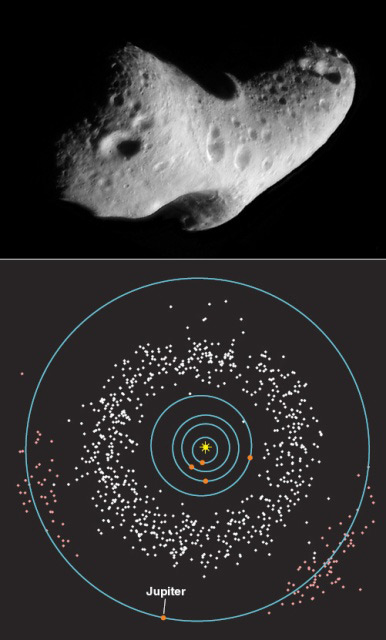

Theyfirst looked at the current configuration of the mainasteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, which has remained largely stablefor 4 billion years. Astronomers had discovered a series of gaps in the mainbelt known as Kirkwood gaps back in the 1860s. These unstable regions arerelatively empty of asteroids because of Jupiter's and Saturn's currentgravitational influence.

Theresearchers started their simulation with a uniform distribution of main beltasteroids larger than 30 miles (50 km) in diameter, but ended up with far morethan what actually remains in real life. The simulated asteroid belt matchedthe real asteroid belt quite well on the sunward-facing sides of the Kirkwoodgaps, but the real asteroid belt is largely devoid of asteroids on theJupiter-facing sides.

Thatpuzzle came together only when Minton and Malhotra ran other simulations whichincluded the giant planet migration. The simulated asteroid patterns thenmatched up "surprisingly well" with the current main beltconfiguration, Minton said.

Collateraldamage

Giantplanets may have scarred our solar system in other ways. The inner systemplanets suffered a periodof heavy bombardment around 3.9 billion years ago, which some scientistsargue may have represented a spike in asteroid impacts rather than just thenormal planetary formation chaos.

Thenew simulation may hint at the bombardment as being a collateral effect of theviolent planet exodus, when main belt asteroids went zipping off like straybullets.

"Wecan't say from this study when that migration happened, but it's a goodplausible mechanism," Minton noted. "Once the asteroids get kickedout of the asteroid belt, they have to go somewhere. Earth, the moon and Marsare all great targets for these asteroids."

However,full closure on this case will have to wait for more evidence to turn up.

- Video - Bootprints on Asteroids: Deep Space Astronauts

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Questioning Habitable Planets

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.