NASA's highly anticipated mission to Europa in the next decade may be just the beginning of an ambitious campaign to study the ocean-harboring Jupiter moon.

In the early to mid-2020s, NASA plans to launch a mission that will conduct dozens of flybys of Europa, which many astrobiologists regard as the solar system's best bet to host life beyond Earth. Space agency officials hope this effort paves the way for future missions to Europa — including one that lands on the icy moon to search for signs of life.

"You gotta figure, if the first one works, then we're going to go to Europa again," NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said late last month during a media event at the Los Angeles facility of aerospace company Aerojet Rocketdyne. [Europa May Harbor Simple Life-Forms (Video)]

Studying Europa from afar

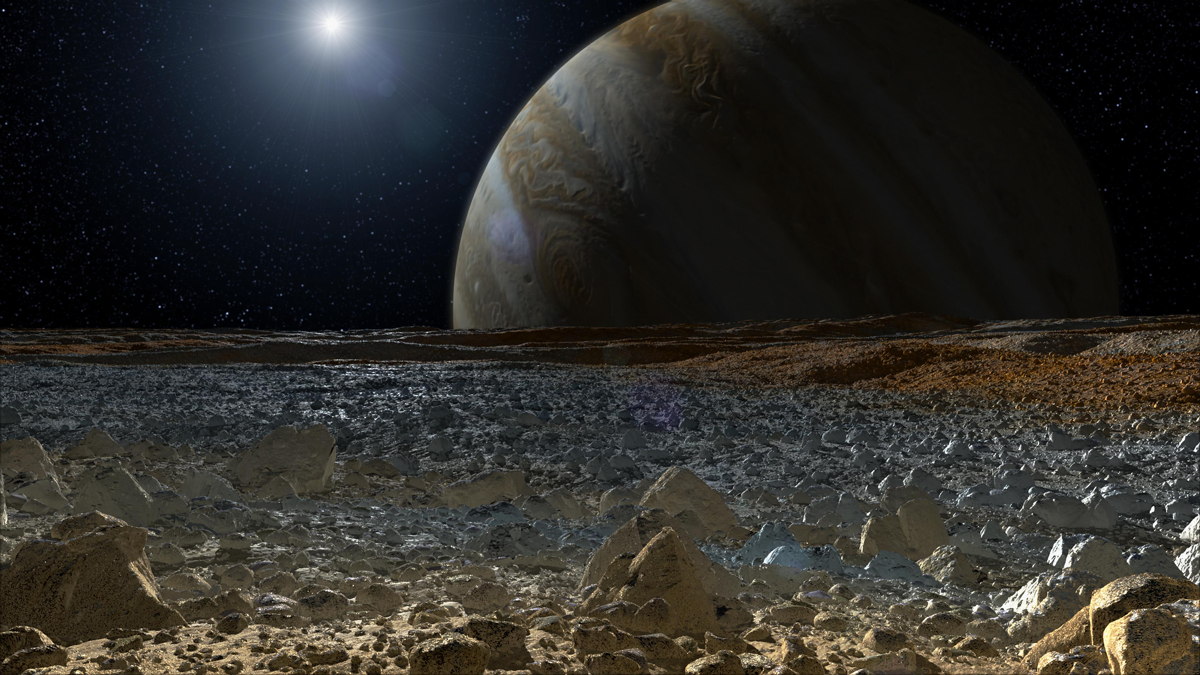

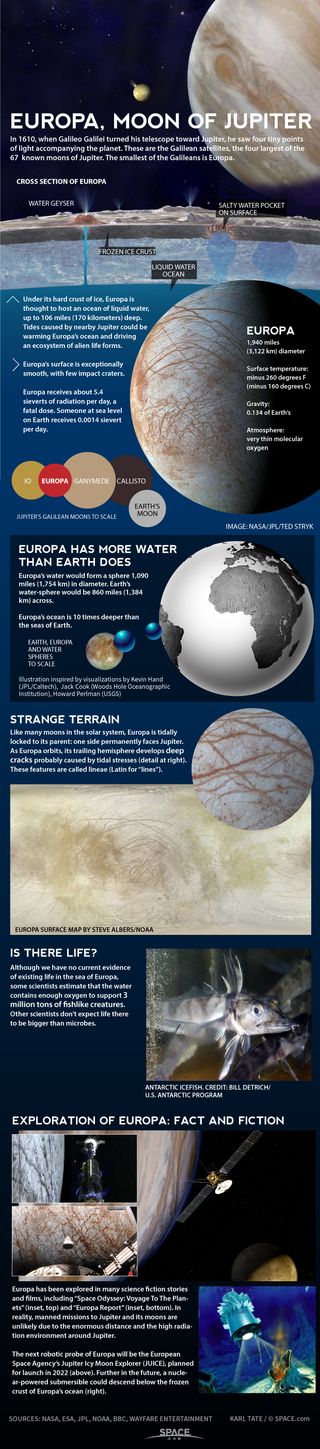

At 1,900 miles (3,100 kilometers) wide, Europa is only slightly smaller than Earth's moon. But the Jovian satellite is very different from the one that lights up Earth's night sky; Europa is covered by a shell of ice, beneath which sloshes an ocean of liquid water.

Scientists think this ocean is in contact with Europa's rocky mantle, making possible a variety of complex chemical reactions. Indeed, the Europan sea may be capable of supporting life as we know it, which explains why astrobiologists have long dreamed of launching a probe to the icy world.

They will get their wish relatively soon. On May 26, NASA announced the nine science instrumentsthat will fly aboard the agency's Europa spacecraft, which is scheduled to blast off in a decade or so.

That gear includes high-resolution cameras, ice-penetrating radar, a heat detector and other equipment. The probe will reach Jupiter orbit and then use these instruments to study Europa's frigid surface and underground ocean during 45 flybys of the moon over the course of about two and a half years.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The goal of the as-yet-unnamed Europa flyby missionis to better understand the moon's ability to support life, not search for signs of alien organisms. As exciting as a Europa life hunt would be, NASA is just not ready to take that step yet, agency officials said.

"Building a life detector is incredibly difficult," Curt Niebur, Europa program scientist at NASA's Washington headquarters, said during a news conference announcing the Europa mission's science payload. "We're not even sure how to go about building it yet." [6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System]

Going back to Europa?

Bolden said that people who are frustrated with the scope of the first Europa mission should exercise a little patience, for the agency does not envision a one-and-done effort at the Jupitermoon.

"My friends in the science community — they don't have a lot of faith, either in us at NASA or in Congress, to fund another Europa mission, so they'd like to get everything on this first mission," he said at the Aerojet Rocketdyne facility on May 26.

"That is a sure recipe for disaster, when you try to do all things with one vehicle. We need to do incremental approaches to studying Europa," Bolden added. "We're going to fly a Europa mission in the 2020s sometime, and hopefully, what we find will whet our appetite and there will be follow-on Europa missions."

Indeed, NASA is already thinking, in a preliminary sense, about possible next steps at Europa, said Jim Green, head of the space agency's Planetary Science division.

"At this stage, we are doing some studies — very elementary studies — about landed missions," Green said during the May 26 science-instrument news conference.

NASA tends to study alien worlds in a series of increasingly ambitious steps; a flyby generally comes first, followed by an orbital mission and then a lander or rover. But the initial Europa effort, with its 45 flybys, will basically serve as an orbital mission in terms of science return, Green said, so putting a probe down on the moon's surface is the logical next step.

Indeed, the flyby probe will, in some ways, serve as a scout, returning supersharp images and other data — such as information about the thickness of Europa's ice shell — that will help researchers plan out a potential surface mission in the future.

"We actually don't know what the surface of Europalooks like at the scale of this table, at the scale of a lander — if it's smooth, if it's incredibly rough, if it's full of spikes," Niebur said. "Without knowing what the surface even looks like, it's difficult to design a lander that could survive."

Ideally, Green said, a landed mission to Europa would not be restricted to its surface. Rather, the mission would get beneath the moon, coming into contact with the ocean, or at least with smaller pockets of liquid water trapped under the ice.

"It'd be great to think that the results from this particular mission would lead, in the next decade, to some new and exciting concepts about potentially getting underneath the ice shell," Green said.

"We need to really make those steps — methodical steps in scientific understanding — to determine indeed if this body can be penetrated in a way to be able to get under the ice shell," he added. "But that's, indeed, in the distant future."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.