A gigantic supersonic parachute that NASA is developing to help land heavy payloads on Mars was torn apart during yesterday's "flying saucer" test flight over Hawaii, agency officials said.

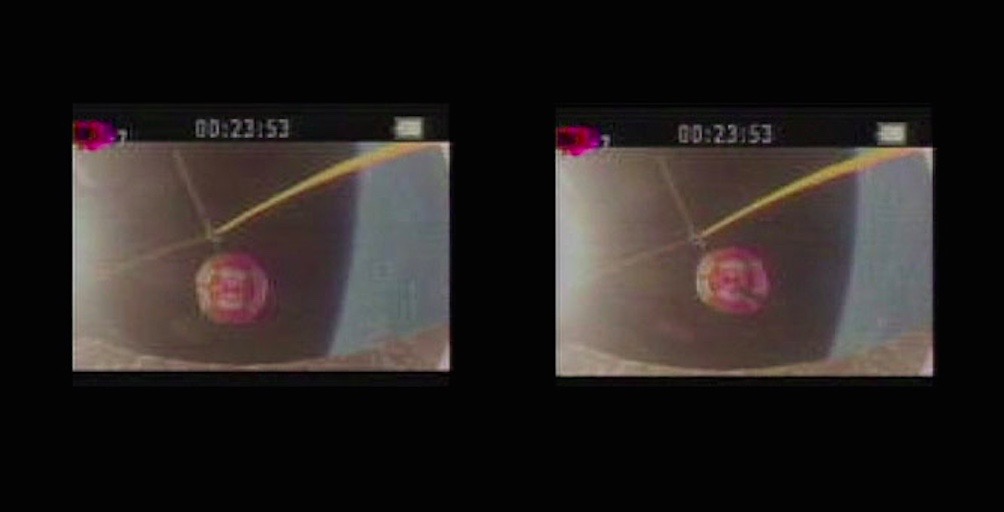

The 100-foot-wide (30 meters) parachute — the biggest such chute ever deployed — unfurled well and apparently inflated fully, or nearly fully, Monday (June 8) before being ruptured by the fast-rushing air during the second flight test of NASA's Low-Density Supersonic Decelerator (LDSD) project.

"At some point at or near full inflation, the parachute was damaged, and the damage propagated further until the parachute could no longer survive the harsh supersonic environment," LDSD principal investigator Ian Clark, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference today (June 9). [Test Flight Photos for NASA's 'Flying Saucer']

"On this project, we're pushing the limits of our technologies, our engineering and our understanding of aerodynamic decelerators," Clark added. "This year, the physics of supersonic parachutes pushed back on us."

Supersonic flight test

The LDSD program is developing technology to help get human habitat modules and other heavy gear down softly on the surface of Mars.

The big supersonic chute — which is twice as wide as the parachute that slowed the descent of NASA's Curiosity rover through the Martian atmosphere in August 2012 — is one of two core components of LDSD tech. The other is a "supersonic inflatable aerodynamic decelerator" (SIAD), a saucerlike piece of equipment designed to fit around the rim of an atmospheric entry vehicle, increasing its surface area (and thus its drag).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA is developing two SIAD versions. One measures 20 feet (6 meters) wide after inflation, while the other is 28 feet (8.5 m) across.

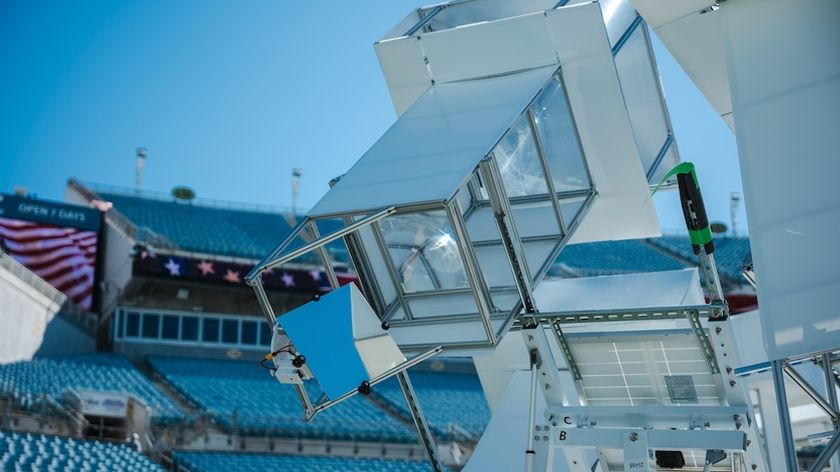

Monday's flight involved the big chute and the 20-foot SIAD, both of which were packed onto a 7,000-lb. (3,175 kilograms) test vehicle. A huge balloon lifted off from the Pacific Missile Range Facility on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, lofting the LDSD craft up to an altitude of 120,000 feet (36,580 m).

At that point, the test vehicle was dropped; it then fired up its onboard rocket motor for 70 seconds, accelerating to about Mach 4 (four times the speed of sound) and an altitude of 180,000 feet (54,860 m), LDSD team members said. (Conditions so high up in Earth's atmosphere mimic those a spacecraft would encounter at Mars, whose air is much thinner than Earth's at sea level.)

The SIAD deployed as planned at Mach 3, and then the test vehicle's ballute — a balloon-parachute hybrid that pulls out the supersonic chute — deployed shortly thereafter, said LDSD project manager Mark Adler, also of JPL.

Everything worked pretty much perfectly up to this point, Adler said. And the supersonic chute performed well initially, appearing to reach full inflation before the tear developed, he added.

"A preliminary look at our load data indicates that the parachute developed full, or nearly full, drag up to the point where that damage can be observed," Clark said.

The team won't know the full details of what happened until they analyze the high-resolution data stored onboard the LDSD vehicle's "black box," Clark said. Recovery boats retrieved the craft from the Pacific Ocean and are ferrying it back to shore. [How to Land on Mars: Martian Tech Explained (Infographic)]

Learning from experience

Monday's trial marked the second flight test for LDSD technology. The first, which occurred in June 2014 from the Pacific Missile Range Facility, proceeded similarly: The SIAD and ballute (a portmanteau of "balloon" and "parachute") worked well, but the parachute was torn apart shortly after deployment.

So the LDSD team modified the parachute, developing a stronger and more robust version for the second test. While this one failed as well on Monday, team members saw signs of improvement.

Last year, "we saw the parachute be damaged very, very early in the inflation process," Clark said. "This year, with the low-resolution data that we have presently, it looks like the parachute remained largely intact, if not entirely intact, up to the point of full inflation. And we also saw more drag being generated out of this parachute this year than we did last year. So, those are both pluses."

Both test flights were broadly successful, Clark and Adler said, stressing that the data gathered will help advance and mature crucial Mars-landing technology.

"We very much want to have these failures occur here in our testing on Earth, rather than at Mars," Adler said. "So it's a success in that we are able to understand and learn more about the parachute so that we can get confidence, and have highly reliable parachutes for when we have a large mission going to Mars."

Clark and colleagues will keep working on the parachute, aiming to test another version from Hawaii next year. The SIAD and ballute, meanwhile, appear ready for use on planetary missions right now, after two successful test runs.

NASA has budgeted $230 million for the LDSD project, which calls for three flight tests. But certifying the supersonic chute will require two successful test flights, so more money will likely be needed for a fourth balloon-aided mission down the road, Adler said.

"We'll need to do some [cost] estimates for what a fourth flight would be, at [NASA] headquarters' request," he said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.