Orbiting 'Rest Stops' to Repair Crumbling Satellites?

More than 1,100 satellites are orbiting the Earth right now transmitting TV shows and phone calls, collecting rainforest data and spying on missile bases around the planet. Most are expensive, costing tens or hundreds of millions of dollars to build, launch and operate.

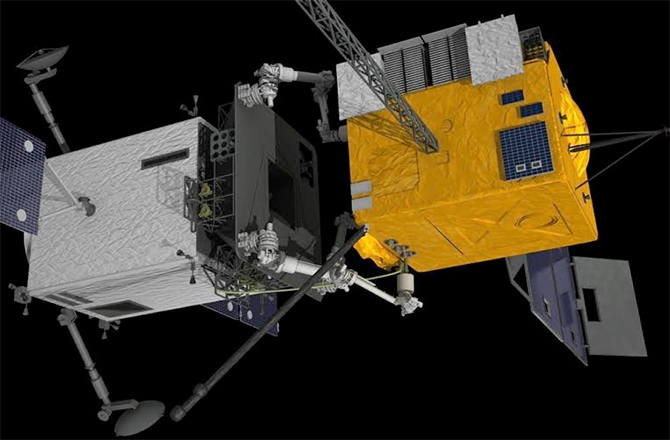

Now NASA wants to build a satellite service station that can gas up and repair aging birds, giving them a few years more life before they fall into the Earth's atmosphere and disintegrate.

5 Space Robots Rescued From Dying Missions

"Is there a way working with humans and robots together to extend the useful life of satellites, by fixing them and by not allowing fuel to spill out, but give it more propellant, close it up and send it on its way?," said Benjamin Reed, deputy director of the Satellite Servicing Program Office at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. "Yes, We have the technologies to be able to do it."

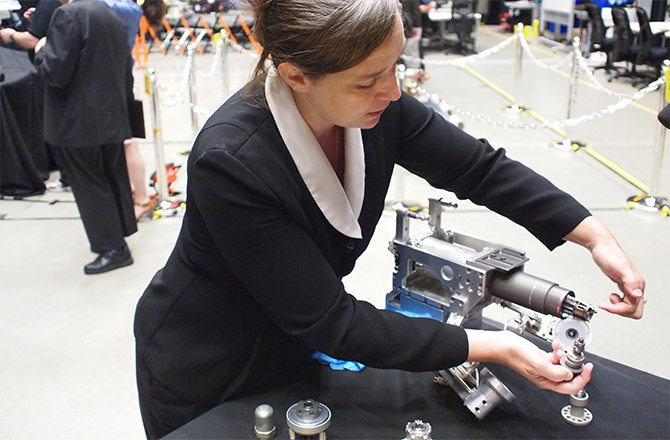

NASA astronauts have been practicing during two Robotic Refueling Missions on the International Space Station in 2011 and 2014, while engineers on the ground at Goddard have been developing new kinds of fuel nozzles, wire-cutters, drills and other robotic tools.

They also built a shiny, gold-foil-covered, 20-foot tall mockup of the Landsat-7 satellite in order to practice docking maneuvers necessary for fueling up in space.

NEWS: NASA Grooming Satellite Repair-Bots

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Other technologies being developed include Raven, a laser-guided sensor that gives precise orbital trajectory of approaching objects. That will be key to any kind of in-orbit docking of two relatively small satellites that have to connect a fuel nozzle that can be just an inch or two wide.

Reed sees a future where a NASA service vehicle hopscotches around low-Earth orbit, docking with satellites that need gas or a tune-up. Additional technologies for in-orbit refueling will also be used in parallel with the upcoming Asteroid Redirect Mission, in which NASA hopes to put a lander on an object, pick up a big boulder, and then bring the rock back to Earth. That mission is funded and scheduled to lift off in December 2020.

But to get a satellite repair vehicle, the commercial satellite industry also has to get on board.

"Yes, industry is interested," said Jean-Luc Froeliger, vice president of satellite engineering and operations at Intelsat. "We have been for many years."

ANALYSIS: CubeSails to Drag Space Junk from Orbit

Intelsat had a deal with a Canadian space company several years ago to develop a servicing mission, but it fell apart. Several other private firms such as Vivisat, as well as firms in Israel and Greece are also putting together financing and possible deals for a satellite tow-truck.

"There's more momentum from the commercial side than the NASA side," Froeliger said. "If you can put a commercial case together, then it's a good deal."

Epic Space Photos of the Week (June 7)

One industry official said that legal issues also have to be solved before NASA or anyone else could launch a repair/refueling vehicle. What if the docking goes awry and the satellite gets dinged up, or knocked into a neighbor's orbit?

Froelinger believes that existing agreements are in place between various satellite providers and operators, as long as NASA or any other firm has some kind of insurance policy.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Eric Niiler is a science and climate reporter at The Wall Street Journal, as well as a writing lecturer at Johns Hopkins Advanced Academic Programs and a contributor to many other places such as National Geographic, the Washington Post, and more. He also has an interest in artificial intelligence and its applications in scientific and medical research. Eric has a master's degree in Science and Medical Journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor's degree in Comparative Literature from the University of California, Berkeley.