First Flybys: From Mercury to Pluto, a History of Solar System Surveys

Humanity is now just one day away from completing the initial reconnaissance of our local home in the universe.

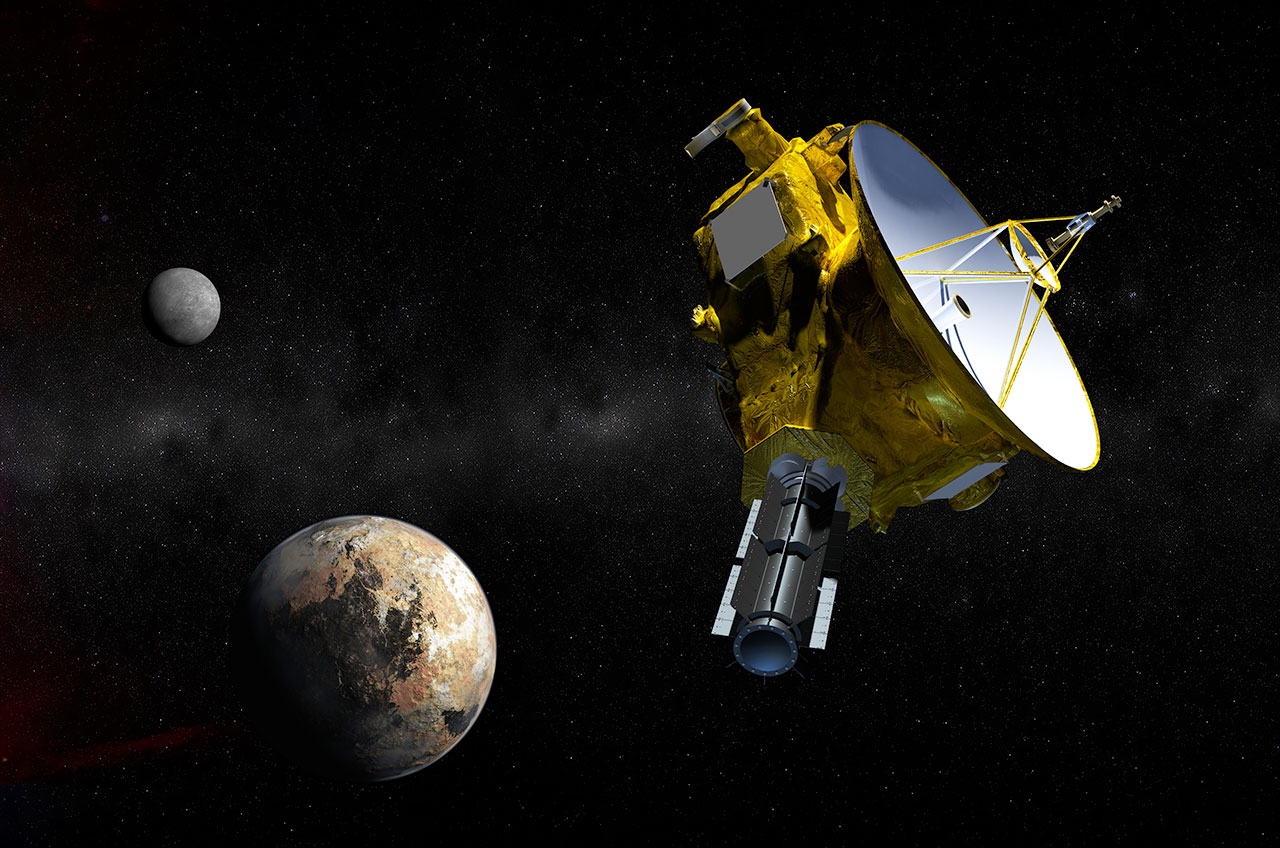

A journey nine years in the making, but which dates back more than a half century to our first encounter with another planet, NASA's New Horizons robotic spacecraft will fly by Pluto at 7:49 a.m. EDT (1149 GMT) on Tuesday (July 14), soaring past the final world in our classical solar system.

The piano-sized probe, traveling at 30,800 mph (49,600 km/h) some 3 billion miles (5 billion kilometers) away from Earth, will come within 7,800 miles (12,500 km) of the dwarf planet, flying close enough to Pluto that if New Horizons was the same distance away from Earth, its camera would not only discern New York City, but also the ponds within Manhattan's Central Park. [New Horizons' Pluto Flyby: Complete Coverage]

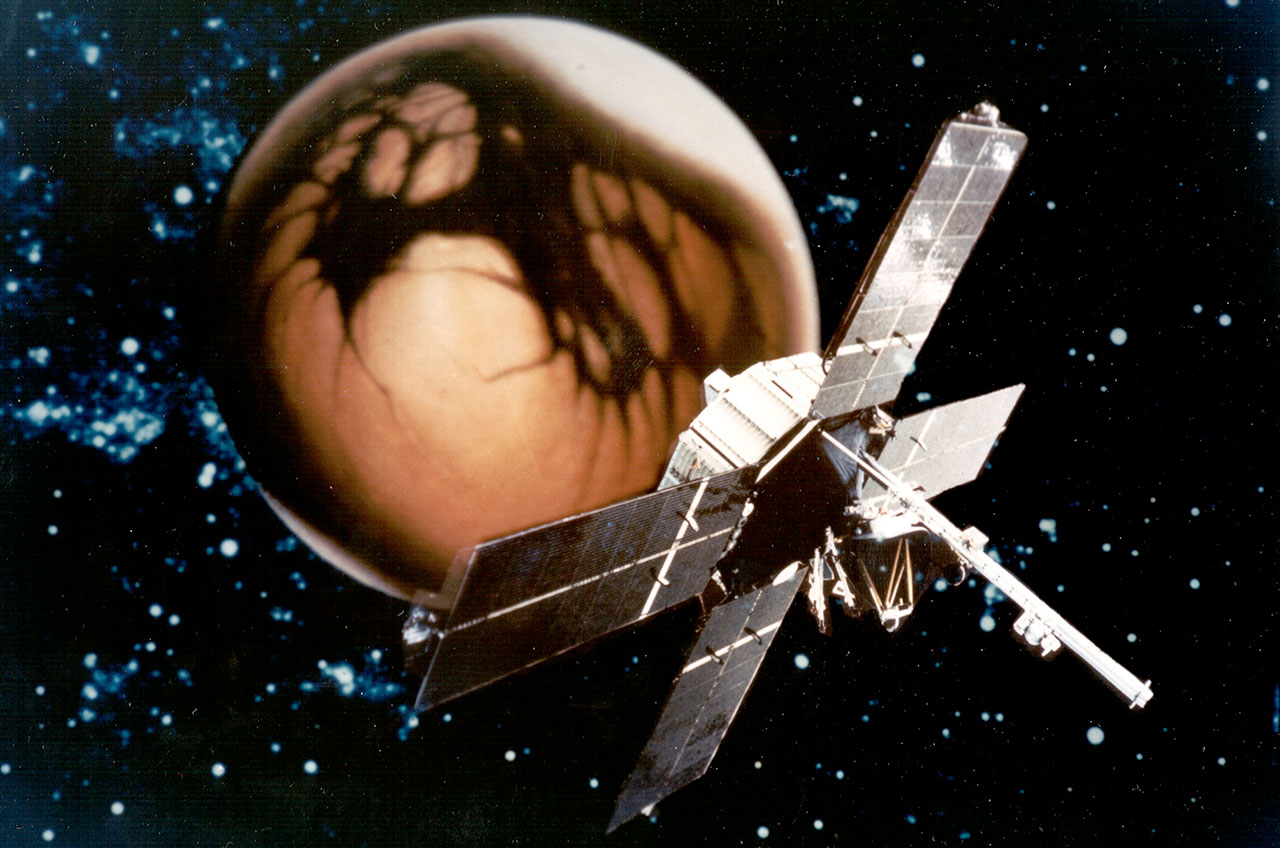

By cosmic coincidence, the same day that New Horizons reaches Pluto is also the 50th anniversary of the first flyby of Mars. On July 14, 1965, NASA's Mariner 4 probe initiated our exploration of the Red Planet and marked the second world visited on our ongoing quest to tour the sun's sphere of influence.

Out to the inners

The first-ever successful planetary flyby preceded Mariner 4 by three and a half years.

NASA's Mariner 2 spacecraft became the first mission to send back data from another planet when it flew by Venus on Dec. 14, 1962. The hexagonal probe, with its pyramid-shaped mast, twin rectangular solar panel wings and large dish antenna, came within 22,000 miles (35,000 km) of the second 'rock' from the sun.

Mariner 2 made a number of discoveries about our sister planet, including Venus' slow retrograde rotation, its hot surface temperatures and the extent of its constant cloud cover.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Out of the 30 or so probes to reach Venus in the years since Mariner 2, more than half made flybys (as opposed to orbiting or landing) — though some failed to return data and others were just on their way to another planet. One of those missions also made the first-ever flyby of Mercury. [Gallery: The Solar System's Deep-Space Probes]

Twelve years after Mariner 2, and just one month after its own flyby of Venus, Mariner 10 soared past the innermost planet on March 29, 1974. Despite mechanical issues on its way out from Earth, the eight-sided spacecraft revealed Mercury's magnetic field and metallic core during its three flybys of the planet.

Unlike Venus, Mercury has only been visited by one other probe to date, NASA's MESSENGER, which first flew by the planet three times in 2008 and 2009, before arriving in orbit in 2011.

Onward to the outers

Mariner 4's flyby of Mars returned the first up-close photos of the Red Planet, revealing a cratered surface.

"We'll collect approximately 5,000 times as much data as Mariner 4, and, for a first flyby reconnaissance, we're gonna knock your socks off," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado..

Beyond the asteroid belt — where NASA's Dawn spacecraft is now in orbit about the dwarf planet Ceres— the first visit to the largest planet in our solar system, Jupiter, took place just a month after Mariner 10 left Earth.

NASA's Pioneer 10 robotic emissary flew by the gas giant on Dec. 4, 1973, coming within 81,000 miles (130,000 km) of the huge planet. The hexagonal spacecraft with its large parabolic dish antenna imaged Jupiter and some of its many moons, and took measurements of the magnetosphere, radiation belts, atmosphere and interior.

Seven more probes have flown to Jupiter since Pioneer 10 (an eighth, Juno, is on its way for a July 2016 arrival) — six of them flybys. The most recent was New Horizons, which sped by the planet at 47,000 mph (76,000 kph) on Feb. 28, 2007. The probe flew within 1.4 million miles (2.3 million km) of Jupiter for a gravity assist out to Pluto.

The second mission to fly by Jupiter was also the first to visit Saturn.

Pioneer 11 passed by the ringed planet at a distance of 13,000 miles (21,000 km) on Sept 1, 1979. The spacecraft discovered a new ring ("F") and a new moon (Epimetheus) circling Saturn, and recorded the global temperature.

Far-out flybys

Prior to Pluto, the final two first flybys of a planet in our solar system were carried out by the same probe, NASA's Voyager 2.

After encountering Jupiter and Saturn in 1979 and 1981, respectively, Voyager 2 flew by Uranus on Jan. 24, 1986. At its closest, the craft came within 50,600 miles (81,500 km) of the planet's cloudtops. Sending back thousands of images, the interplanetary probe discovered 10 previously unseen moons and new rings and also found Uranus's unusual magnetic field, a product of the planet's sideways orientation.

Voyager 2 then continued outward, passing by Neptune on Aug. 25, 1989. Making its closest approach to any of the four planets it visited, the spacecraft came within 25,000 miles (40,000 km) of the blue world. Voyager 2 revealed the "Great Dark Spot" (which has since disappeared) and observed Neptune's moon Triton.

When the Mariners, Pioneers and Voyager made their first flybys of their respective worlds, Pluto was still considered the final planet not yet explored. Now reclassified a dwarf planet, Pluto remains — at least for the next day — as the last major world to be visited.

"New Horizons isn't completing the reconnaissance of our solar system," said Stern. "We are always very careful to add a word — this is the 'first' era of reconnaissance. I would call this the end of the beginning."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2015 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.