Weird 'Buckyballs' May Be at Root of Milky Way Mystery

Soccer-ball-shaped carbon molecules known as buckyballs may be the cause of mysterious bands seen in light across the Milky Way that have puzzled astronomers for nearly a century, a new study reports.

The discovery suggests these carbon spheres may be commonplace across the universe, and may even be sources of organic molecules that are key to the origin and evolution of life, scientists added.

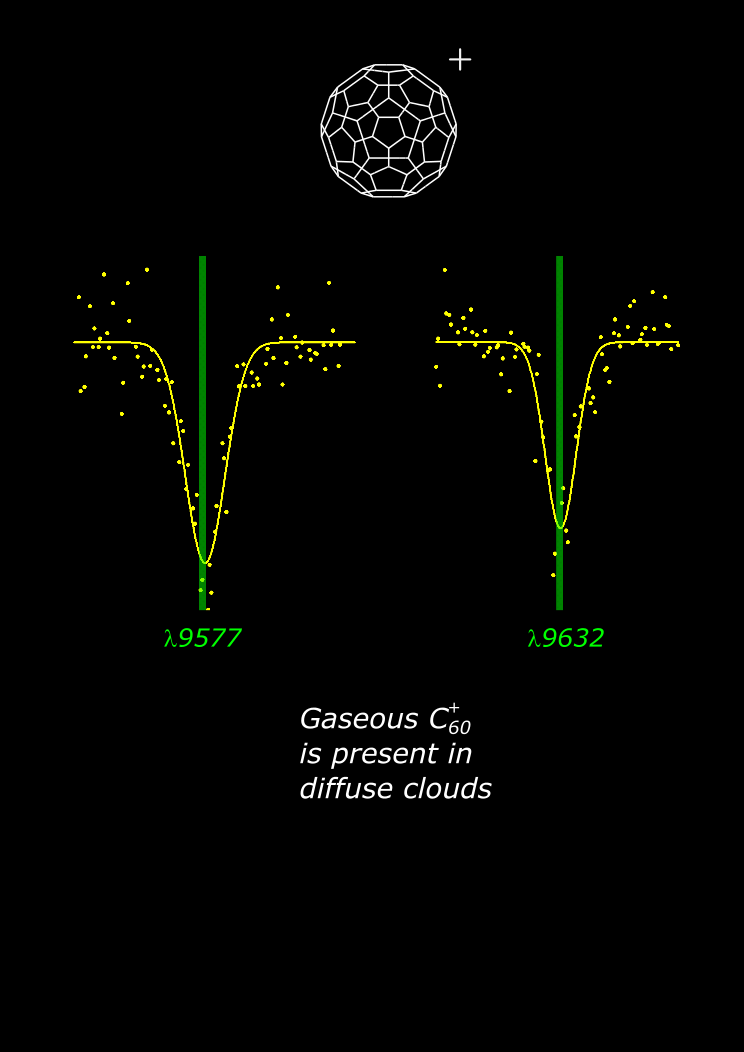

Astronomers often focus on dark lines in the spectra of the light streaming down on Earth from outer space. These "absorption lines" are fingerprints left behind by molecules, each of which absorbs a unique pattern of colors. Absorption lines can yield insights into the composition of whatever the light passed through on its way to Earth, be it the outer layers of a star, a cloud of interstellar gas or the dusty birthplace of a planet. [Tiny Soccer Balls Found In Space (Video)]

Nearly 100 years ago, astronomers began spotting unknown absorption bands associated with the interstellar gas and dust of the Milky Way and other galaxies. More than 400 of these "diffuse interstellar bands" have been found to date, and their cause is "often cited as the biggest enigma of observational astronomy," study co-author John Maier, a spectroscopist and chemical physicist at the University of Basel in Switzerland, told Space.com.

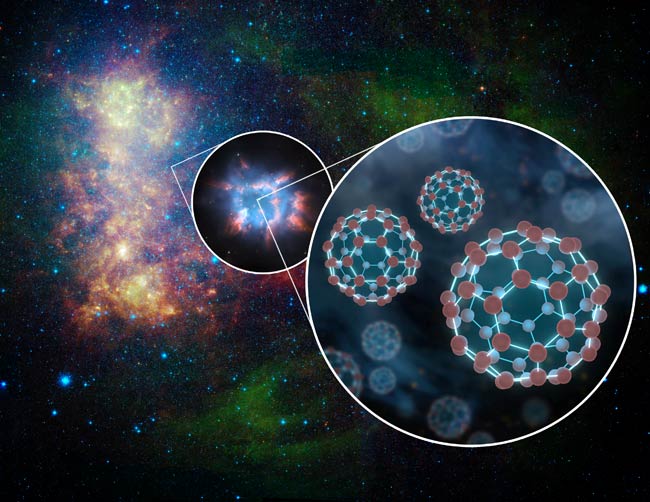

In 1994, researchers suggested that some of these absorption bands might arise from buckyballs, which are cagelike spheres also known as C60, since each molecule is made up of 60 carbon atoms.

Buckyballs, also known as fullerenes, are named after their resemblance to the architect Buckminster Fuller's geodesic domes, a giant example of which is found at the entrance to Disney World's Epcot theme park in Florida. Discovered in 1985, buckyballs are about 1 nanometer in size, or about one ten-thousandth the average diameter of a human hair.

Five years ago, scientists confirmed that buckyballs exist in space around stars. Now, Maier and his colleagues have found the first unambiguous evidence that buckyballs exist in the interstellar medium between stars in the Milky Way.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the lab, the researchers created a positively charged version of C60 known as C60+, which can form when buckyballs are bombarded with radiation. They cooled a gas of C60+ to the kind of temperatures found in deep space — about minus 449 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 267 degrees Celsius). They next tested what C60+'s absorption bands were. Altogether, this project took 20 years, Maier said.

The researchers found that buckyballs are responsible for two diffuse interstellar bands, marking the first time investigators have identified a culprit behind any of these mysterious features.

"The whole mystery has not been solved, but perhaps this is the beginning," Maier said.

Previous research suggested buckyballs are created in dying stars and pushed out into planetary nebulas. These new findings suggest buckyballs ultimately make their way into diffuse clouds that provide the seeds for the formation of new stars.

"C60+ may well be ubiquitous in space and stable in very hostile environments," Maier said. "Buckyballs may even be the precursors of important organic molecules necessary for the formation of life on planets."

Future research can investigate whether other diffuse interstellar bands are caused by buckyballs laced with metals and other elements, Maier said.

The scientists detailed their findings in online Wednesday (July 15) in the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us