30 years of polar climate data converted into menacing, 6-minute song

Geoenvironmental scientist Hiroto Nagai used publicly available climate data from the North and South poles to compose an ominous-sounding chamber music piece.

A Japanese scientist has taken inspiration from the climate crisis to compose music that sounds as ominous as current forecasts of ecological breakdown.

Hiroto Nagai, a geoenvironmental scientist and associate professor at Rissho University in Tokyo, compiled publicly available climate data from the Arctic and Antarctic to produce a 6-minute chamber music composition for string quartet. Musicians performed the piece in February 2023, with footage of the recital released on YouTube two months later. Nagai then gathered feedback and described the work that went into the music in a study, which was published online April 18, 2024 in the journal iScience.

The aim of the experiment was to raise awareness of climate change through art. "One of the main insights from the participants is that music, unlike usual graphical representations of scientific data, evokes [an] emotional impression first," Nagai wrote in the study. "It grabs the audiences' attention forcefully, while graphical representations require active and conscious recognition instead."

The climate data used for the composition spans the last 30 years. Nagai extracted records of solar radiation, surface temperature, precipitation and cloud thickness from four weather stations in the Arctic and Antarctica to represent the "energy budget" of Earth's poles.

Related: NASA's twin spacecraft will go to the ends of the Earth to combat climate change

The energy budget of a region is the balance between the amount of energy incoming from the sun and the amount of energy that is reflected back into space. Earth's energy budget depends on the albedo effect, which dictates that dark-colored surfaces, such as oceans and forests, reflect less energy back into space than light-colored surfaces. Given that polar regions are covered in snow and ice, they reflect almost all the solar radiation that reaches them.

But climate change is reducing the amount of ice at the poles, throwing Earth's energy budget off kilter. Rising temperatures are causing entire ice shelves to collapse and the extent of sea ice to shrink year-on-year. As ice melts, it exposes darker surfaces that absorb more solar radiation, leading to increased warming and triggering a climate feedback loop.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

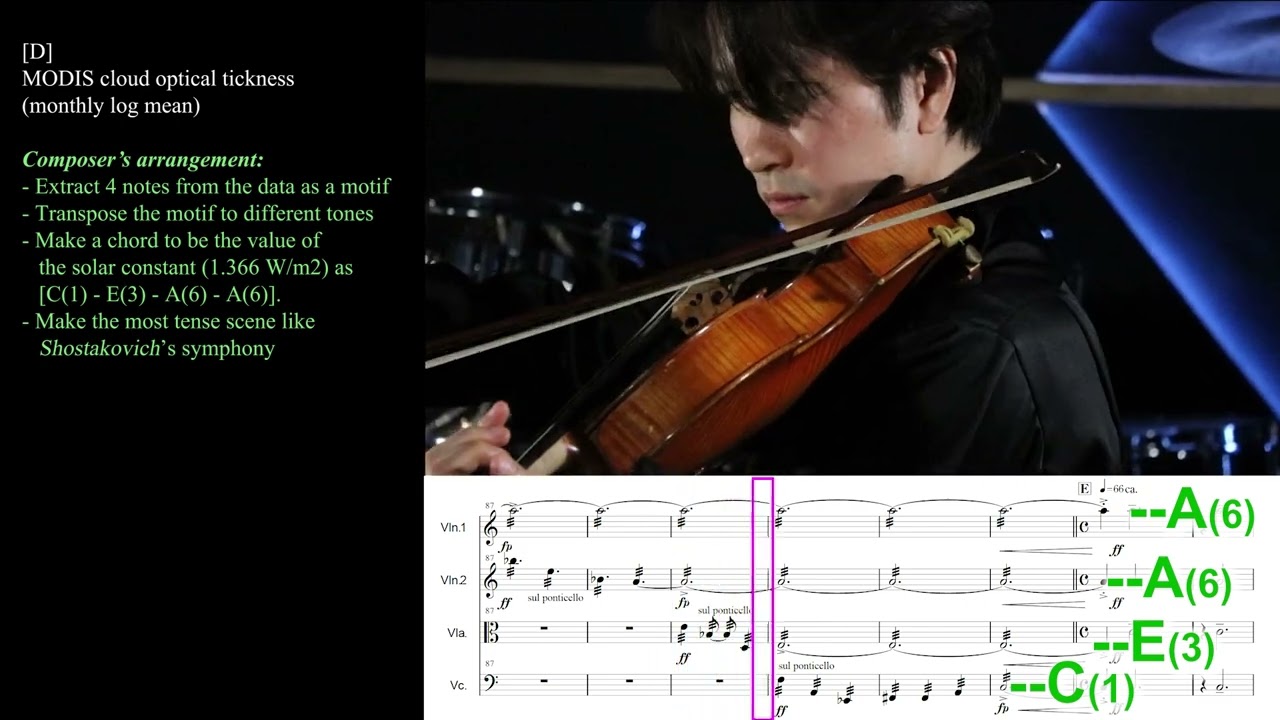

Nagai used software to convert the data into sheet music. He separated the various datasets into sections labeled A to I, with the shape of the music on the page roughly mirroring the curves of the data. He then made stylistic additions and changes to the music to avoid repetitive sequences.

The process of transforming data into sound is known as sonification. While researchers previously tried this method, the resulting soundscapes didn't sound like conventional music due to a lack of stylistic changes.

"There is a tendency to avoid intentional interventions or edits (i.e., contamination) in the original data," Nagai wrote in the study. "As a result, while the information from the original data are preserved as much as possible, composed musical pieces often contain a monotonous progression and lack any significant dynamics."

Nagai's composition, titled "Polar Energy Budget," includes both data-derived melodies and free arrangements. The choice of a string quartet (two violins, a viola and a cello) was based on the four-voice structure and diversity of playing techniques of these instruments.

"This marks a significant turning point from an era where only scientists handled data to an era where artists can freely use data to create their works," Nagai concluded in the study.

Sascha is a U.K.-based trainee staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.