Mars Rover Curiosity Gives Advanced Sunspot Warning from Sun's Far Side

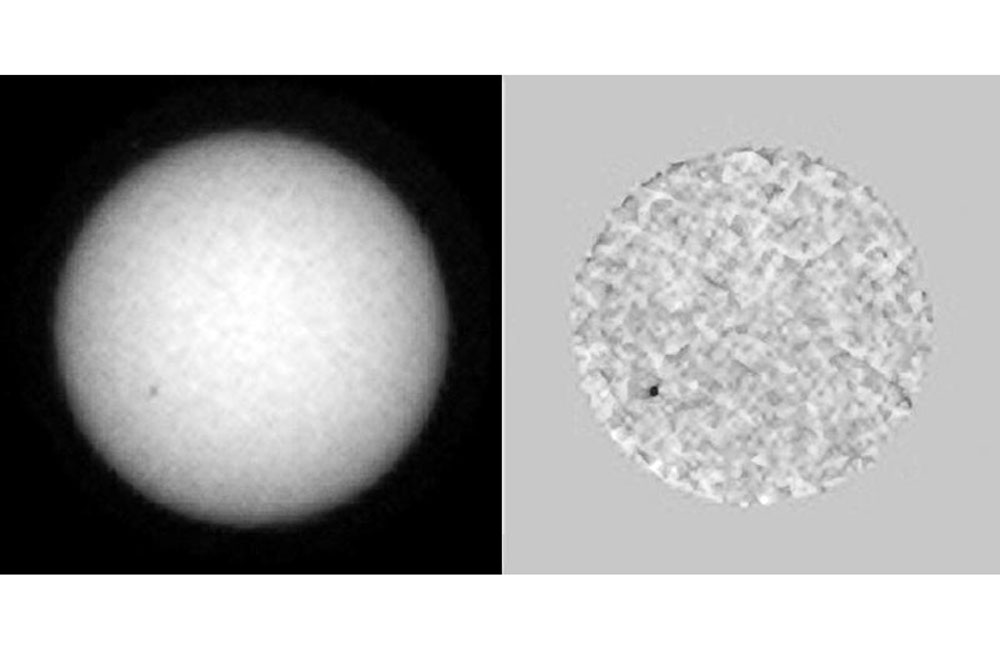

The Curiosity rover on Mars has turned its cameras skyward and found sunspots brewing on the far side of the sun, a view that's impossible to get from Earth.

Sunspots can often spawn into solar flares or massive eruptions, known as coronal mass ejections, which can pose a hazard to astronauts and satellites in space, and disrupt satellite navigation and communications systems on Earth. So spotting sunspots before they make their way to the sun's front — the star fully rotates around once per month — is a major heads up.

Sun-watching observatories on Earth, and most space-based telescopes, currently can only see the side of the sun facing the Earth. NASA's sun-monitoring STEREO-A spacecraft is currently on the opposite side of the sun from Earth, so while it might see farside sunspots, it is unable to communicate them to Earth because the sun blocks the way.

Mars, however, has just recently completed its passage behind the sun, as viewed from Earth. The Curiosity rover tracked the sunspots on the far side from June 24 to July 8, a few days before Earthbound cameras were able to spot them. In April, Curiosity also caught sunspots on the sun's back; these ultimately led to two solar eruptions — one of which caused space weather that affected Earth.

"Tracking the sunspot activity on the far side of the sun is useful for space-weather forecasting," Yihua Zheng, project leader for NASA Space Weather Services at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a statement. "It helps us monitor how the sunspots evolve and grow before they become visible from this side."

When Curiosity first caught sight of a sunspot in April, researchers had intended to observe Mercury in Mars' sky moving past the sun.

"We saw sunspots in the images during the Mercury transit, and I was trying to distinguish Mercury from a sunspot," Mark Lemmon, a researcher at Texas A&M University who works on Curiosity's Mast Camera, said in the statement. "I checked with heliophysicists who study sunspots and learned that STEREO-A was out of communications, so there was no current information about sunspots on that side of the sun. That's how we learned it would be useful for Curiosity to monitor sunspots."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Usually, Lemmon uses Curiosity's Mast Camera to examine the way the sun's light deflects through the Red Planet's atmospheric dust. Curiosity has been exploring Mars' surface since August 2012, and the rover will soon test its sample-collecting drill again as it examines ground higher and higher on the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 kilometers) Mount Sharp to tell researchers about the planet's surface. And in the meantime, when the timing is right, Curiosity can look upward and warn Earthlings about weather heading toward this planet.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.