Amazing Photos of Pluto Reveal Glaciers and Hazy Atmosphere

Stunning new images of Pluto by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft show flowing ices, a complicated surface covered in mountain ranges and a surprisingly far-reaching atmosphere.

At a news conference today (July 24), members of the New Horizons team spoke about the incredible new science being pulled from data collected by the probe, which performed history's first flyby of Pluto on July 14. Among other findings, scientists announced big surprises in the study of Pluto's atmosphere, as well as the discovery of what appear to be flowing fields of ice in Pluto's "heart."

"Pluto has a very complicated story to tell," Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, said at the news conference. "There is a lot of work that we need to do to understand this very complicated place." [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

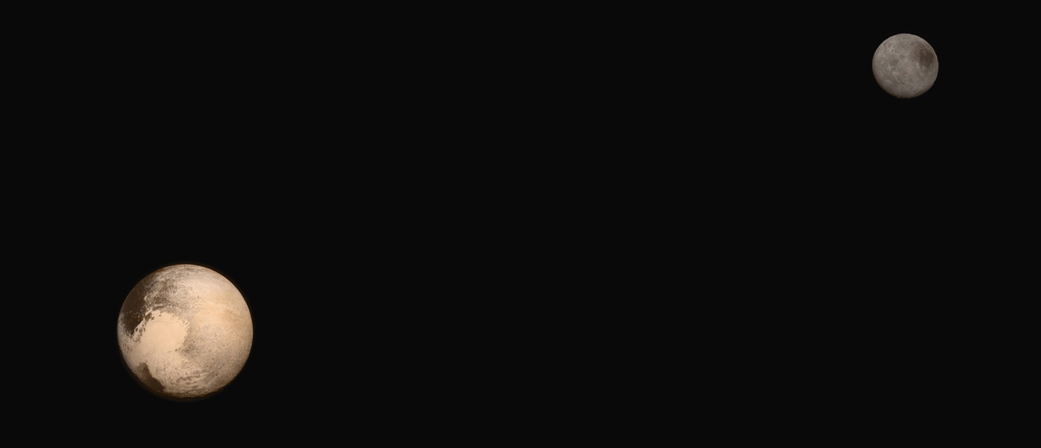

One of the new images released today is a gorgeous global view showing half of Pluto's surface, lit by sunlight, with the heart-shaped region informally known as Tombaugh Regio in the lower-left quadrant. The new image shows features on the surface as small as 1.4 miles (2.2 kilometers), or twice the resolution of a similar image released on July 13.

The image shows Pluto's surface in "true color," or as it would appear to the human eye. It combines data from New Horizons' Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) and Ralph instruments.

Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, appear together in a new, "true color" portrait that highlights the reddish hue of Pluto compared to Charon's gray tone. Scientists think Pluto's red color is the result of particles created in its atmosphere, through methane's interaction with UV light. The particles stick together, growing heavier, and eventually rain down on the surface.

On the other hand, new observations of Charon suggest that it has "much less atmosphere than Pluto, if any," Stern said. The probe will send back more data on Charon's atmosphere in September.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"For now, all that we can say is, it's a much more rarefied atmosphere [than Pluto's]," Stern said. "It may be that there's a thin nitrogen layer in the atmosphere, or methane, or some other constituent. But it must be very tenuous compared to Pluto — again, emphasizing just how different these two objects are despite their close association in space."

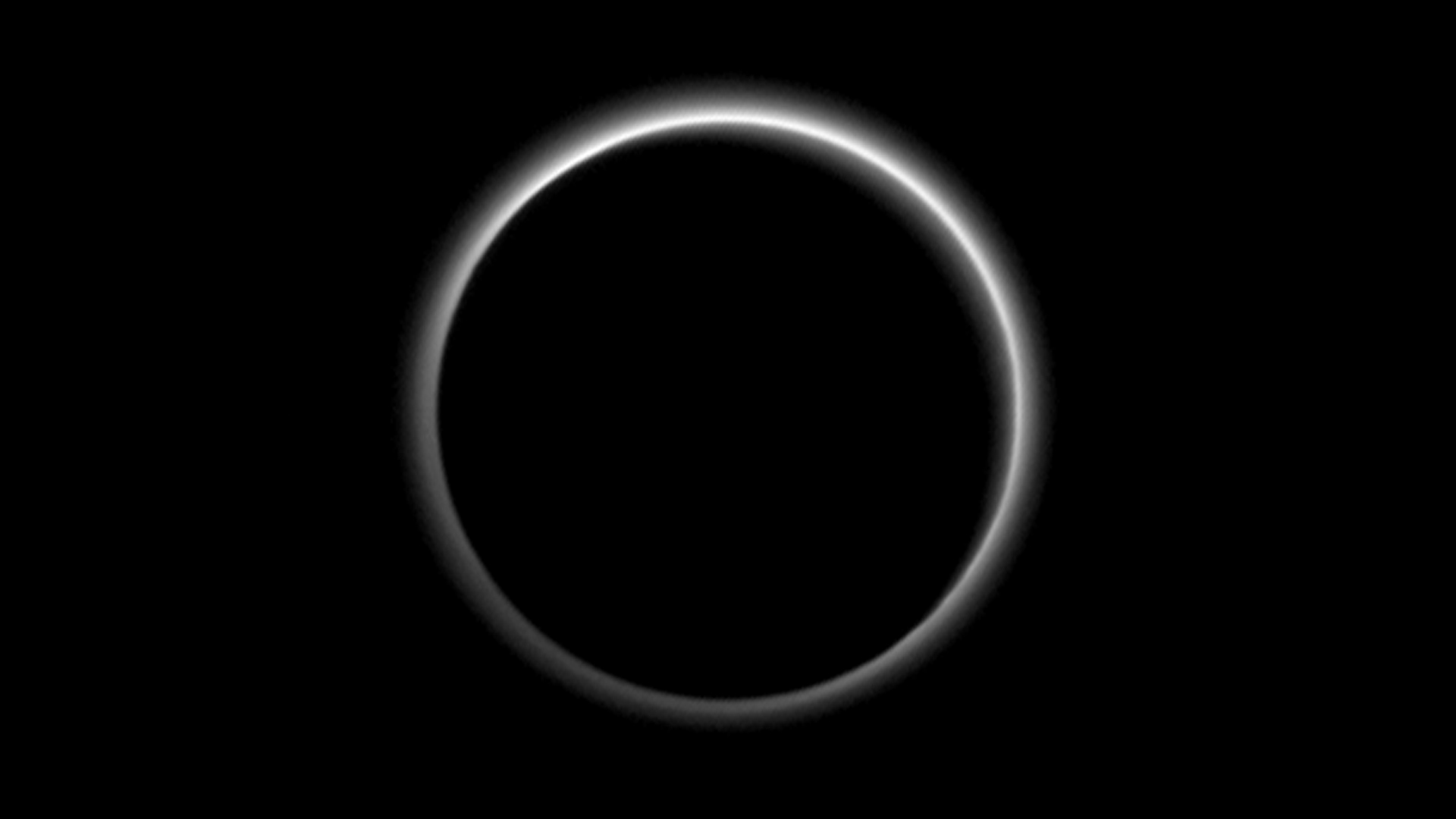

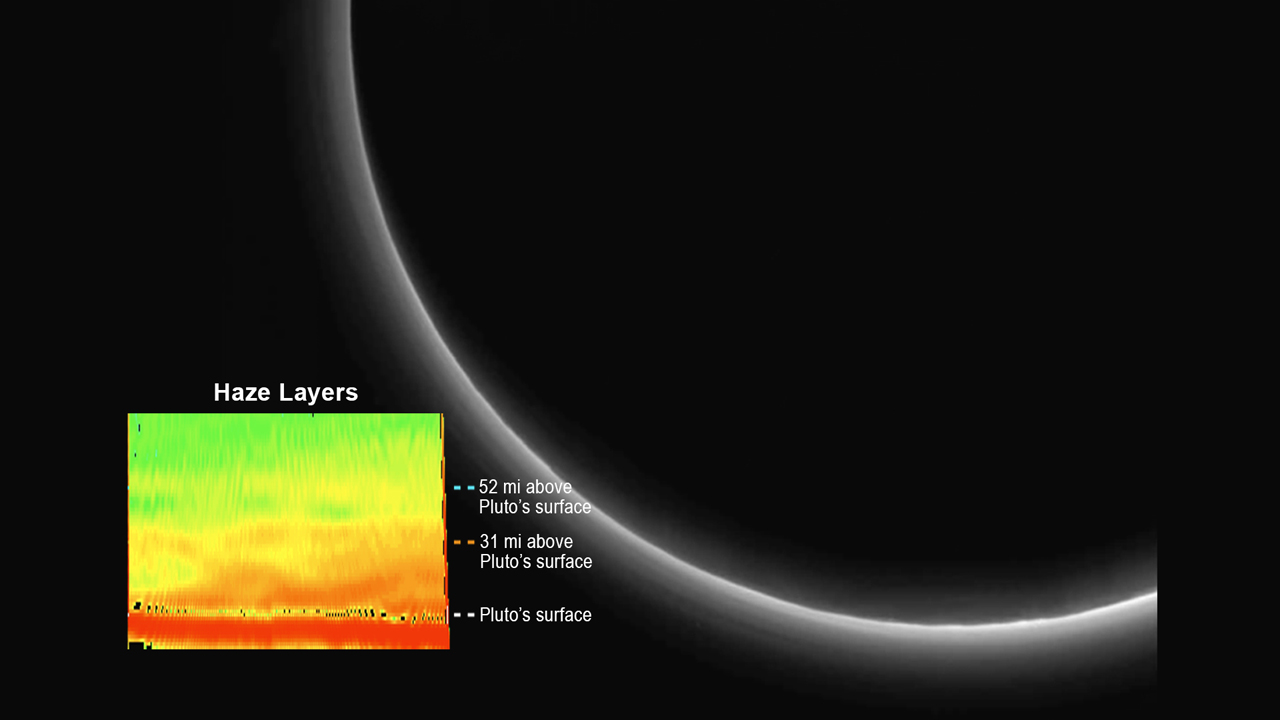

In a stunning image taken from beyond the far side of Pluto, in which the dwarf planet eclipses the sun, scientists can see a haze in the Plutonian atmosphere.

"This is one of our first images of Pluto's atmosphere. [It] stunned the encounter team," said Michael Summers, a New Horizons co-investigator based at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, at today's news conference. "For 25 years, we've known that Pluto has an atmosphere. But it's been known by numbers. This is our first picture. This is the first time we've really seen it. This was the image that almost brought tears to the eyes of the atmospheric scientists on our team."

The haze is created by the particles that scientists think eventually fall to the surface and give Pluto its reddish hue. The haze extends at least 100 miles (160 km) above the surface of Pluto, or five times higher than models predicted, according to Summers, who called the discovery "a big surprise." Scientists previously thought the upper layers of the atmosphere would be too warm for hazes to form, he said.

"We're going to need some new ideas to figure out what's going on," Summers said in a statement from NASA.

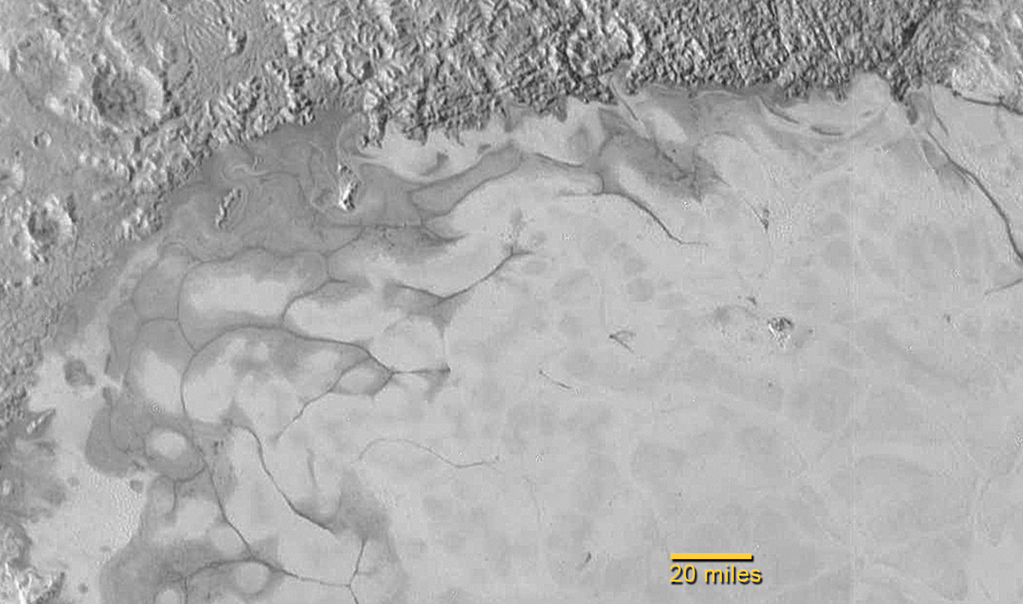

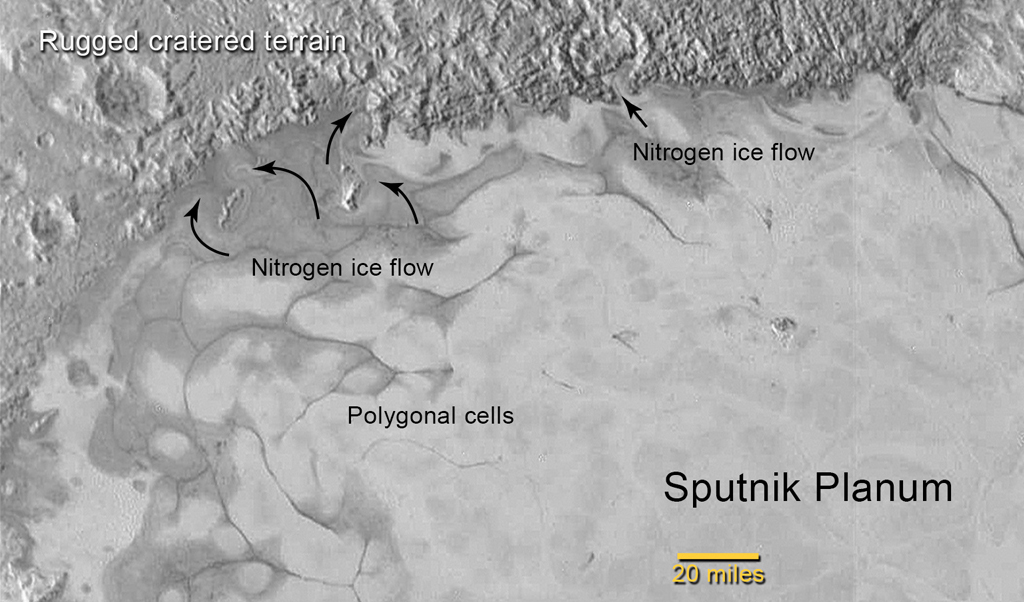

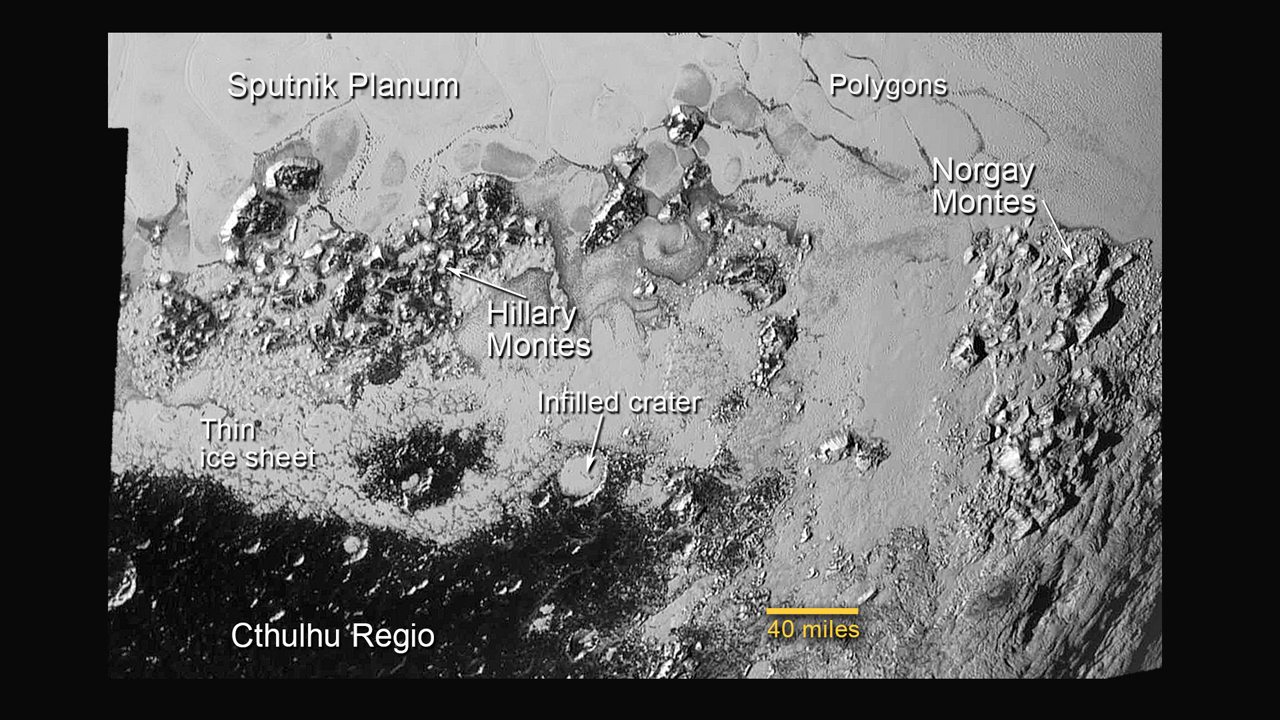

In another set of new images, scientists revealed what appears to be a wide field of glaciers flowing across Pluto's surface. The flowing ice field is easily spotted in images of the dwarf planet: It's the smooth, light-colored upper-left lobe of the heart-shaped region — an area unofficially known as Sputnik Planum. [Fly Over Pluto's Hillary Mountains and Sputnik Plain (Video)]

Scientists think that, unlike glaciers on Earth, the ice in Sputnik Planum is made of nitrogen, carbon monoxide and methane. At the frigid temperature of about minus 390 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 235 Celsius), water ice "won't move anywhere," because it is too rigid and brittle to flow, said Bill McKinnon, of Washington University in St. Louis, deputy leader of the New Horizons geology, geophysics and imaging team.

But even at such low temperatures, nitrogen, carbon dioxide and methane ices are "geologically soft and malleable," McKinnon said. At the news conference, McKinnon showed regions near the heart-shaped region's upper-left edge where the ice could be seen creeping around other geologic barriers and filling in craters. The images, he said, show "conclusive evidence" of ice flow that may still be happening on Pluto's surface today.

"To see evidence of recent geological activity is simply a dream come true," McKinnon said. "The appearance of this terrain, the utter lack of impact craters on Sputnik Planum, tells us that this is really a young unit."

McKinnon also noted another interesting finding that has surfaced from the New Horizons data: Pluto is very close to being perfectly spherical.

"We actually can't detect any obliqueness or out-of-roundness in the body," McKinnon said. Many other bodies in the solar system have distortions to their roundness, which "tells you about their history," he said.

"Pluto was probably spinning very, very fast after what we believe to be a giant impact that led to the formation of [Charon]," McKinnon added, noting that the gravitational pull of the two bodies on each other would have, over time, slowed down Pluto's rapid rotation.

The New Horizons space probe made its closest approach to Pluto on July 14. The entire data set that it collected during its flyby of the dwarf planet will take 16 months to download back to Earth. The wide variety of features on Pluto's surface poses many questions that will keep scientists busy for years to come, mission team members have said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter