Tiny Space Rocks Help Settle Astronomical Debate

A pair of miniscule meteorite grains has helped astronomers settle a long-running debate on the origins of space dust belched out by dying stars.

Chemical analysis of the grains, which formed before the solar system and our Sun, confirmed they contained two forms of a metal oxide that astronomers had only seen hints of in observations of stars reaching the end of their life cycle.

"It's always been believed that this [material] was the first thing that forms from these stars," said Larry Nittler, a co-author of the study and a staff scientist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

But before now, researchers weren't sure both forms of the metal, one crystalline and the other not, were belched out in the early phases of a certain type of dying star called an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star. Such stars are the most significant source of interstellar dust in the Milky Way, researchers said. Understanding how it is expelled by AGB stars, and in what form, is crucial to determining how chemical elements cycle from stars to interstellar space and, eventually, coalesce into new stars, planets and the building blocks for people.

"This is the start of that entire process," Nittler told SPACE.com.

AGB stars were once like the Sun, but have reached a period in their lifecycle when they are blowing out massive amounts of dust and material in preparation for their eventual slip down to white dwarf status, Nittler said.

The research will appear in the Sept. 3 issue of the journal Science and is the result of collaboration between scientists at the Naval Research Laboratory and the Carnegie Institution of Washington, both in Washington D.C.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Grains from space

The grains themselves were plucked from the Tieschitz meteorite, a space rock that fell to Earth in 1878 in Moravia, located in what is now the Czech Republic.

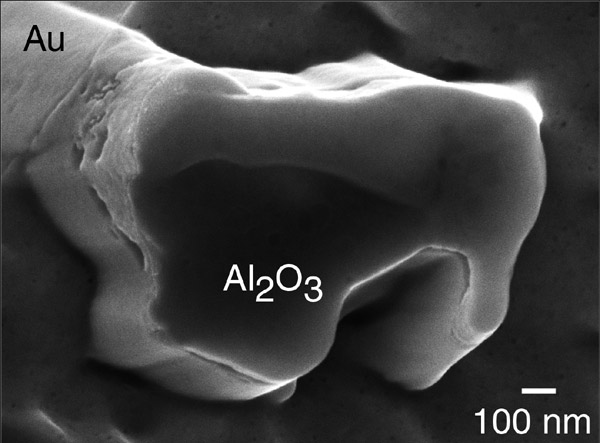

Neither of the grains is larger than a single micron (one-millionth of a meter or about one-fiftieth the width of a human hair), although they are composed of the same material - aluminum oxide. One grain contains a crystalline form of the metal while the other is made of a non-crystalline, amorphous version.

"They're much smaller than a grain of sand, but they can tell you about these vast processes," said Nittler of the presolar grains.

They can be set apart from other early solar system matter because their isotopic oxygen signatures are unlike those found in oxygen samples anywhere else in the solar system, though researchers sifted through hundreds of sample before finding the two presolar grains.

Nittler said the next step is to analyze a much larger number of aluminum oxide grains to see how they compare to these first two.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.