Cassini Spacecraft to Make Final Flybys of 2 Icy Saturn Moons

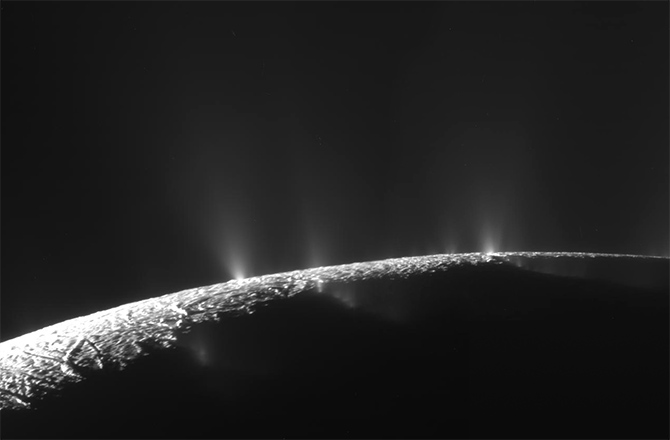

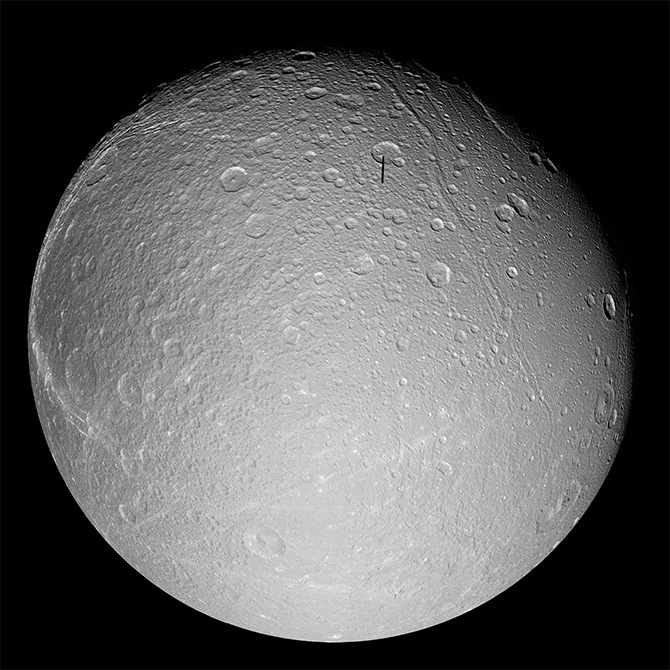

For the next six months, NASA's Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft will get its final look at two icy moons — one famous and one not so well-known. It will fly by the erupting moon Enceladus three times, checking out its plumes in the best detail to date. And it will take one last look at the moon Dione (pronounced die-OWN-ee), which may have eruptions as well.

PHOTOS: Cassini's 10th Year: Recent Saturn Mind Blowers

Why are icy moons so interesting to astronomers? One reason is they represent some of the best chances of finding life in our solar system. Many of these icy moons are believed to host global oceans underneath. Warmed by gravitational interactions with massive Saturn, there could be microbes floating under the surface just waiting for us to examine. [Latest Saturn Photos from NASA's Cassini]

The long last look at Dione will take place Aug. 17, when Cassini will do gravitational measurements to learn more about its interior and icy shell. "There are intriguing hints that perhaps there's something similar going on on Dione that we might have on Enceladus, but we haven't found the equivalent of a smoking gun," Linda Spilker, the Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told Discovery News.

The plumes on Enceladus were first found from measurements by Cassini's magnetometer, which recorded evidence that the magnetic field lines do not go down to the surface — as is what would be expected on an airless body.

ANALYSIS: Cassini Grand Finale: Saturn Mission's Daring End

But similar evidence is so far lacking at Dione. Perhaps it's because the moon is bigger, Spilker says, meaning the plumes are pulled down by gravity and are harder to see. Scientists will also look at Dione from afar in 2017, when the moon passes in front of a background star. If there are plumes erupting from Dione, it would dim the starlight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As for Enceladus itself, three final flybys are planned in 2015 to learn more about its environment: a view of the north pole on Oct. 14, a "plunge" into the known location of a plume Oct. 28, and an attempt to look at the thermal environment of the south pole Dec. 19. [Amazing Photos of Icy Enceladus]

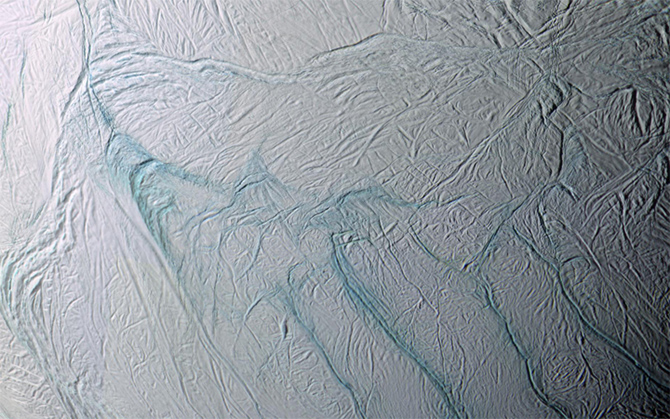

It's now winter time in the south pole of Enceladus, providing a unique opportunity to look at any heat coming from the "tiger stripe s" in that region. These zones are associated with the icy plumes that are coming from Enceladus.

The north pole flyby will allow them to use a "high phase angle" to examine the plumes in more detail; it's sort of the equivalent of driving into the sun with the dust on the windshield, Spilker said, because the sun reflects off the dust. This allows them to measure how the plumes have changed.

PHOTO: Cassini Gets Final, Stunning View of Saturn's Moon Hyperion

And the most spectacular of the trio of flybys will be going deep into a known plume region itself, to measure the gas and particles and learn more about their source. The working theory is that water from the sea floor of Enceladus goes through the cracks below the surface, interacts with the rocky core and heats up, then erupts back above the surface and interacts with colder water. Nanosilica particles have been detected in the plumes, which occur in the presence of hot water.

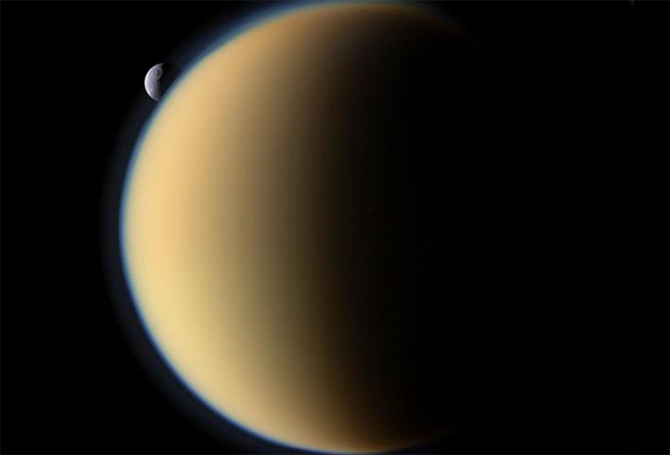

These regular flybys of moons are possible through interactions with the massive Titan, one of the larger moons in the solar system (almost as big as the planet Mercury) and also of interest because it has an ecosystem full of ethane and methane. Its liquid lakes make it unique in the solar system. So Cassini does observations of this intriguing world while taking advantage of its gravity to slingshot to other locations.

PHOTOS: Cassini's Festive Tour of Spectacular Saturn

Perhaps the most spectacular example of this will take place close to the end of the mission, when Cassini uses Titan's gravity to "hop" to a spot in the inner part of Saturn's rings. There, the spacecraft will spend 22 orbits before plunging into Saturn's atmosphere on Sept. 15, 2017.

"We do that to protect those worlds that have an ocean," Spilker explained. When Cassini makes its suicidal plunge, it will point its high-gain antenna at Earth and transmit measurements on Saturn's atmosphere until it begins tumbling, moving it out of contact from Earth in its final moments before destruction.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.