Is That Really Alien Life? Scientists Worry Over False-Positive Signs

The search for life elsewhere in the universe is on the cusp of a new era: When scientists will have the opportunity to study the atmospheres of potentially habitable planets with future, technologically advanced telescopes. Humans have no foreseeable way to travel to these worlds to study them up close, but the chemical mixtures that surround them may reveal the presence of life.

There is no single "smoking gun" for life; no atmospheric mixture that can definitively declare, "Something lives here!" (At least, not that scientists know of). And searching for life from afar carries a heavy burden of proof: Any signal that looks like life could actually be created in some clever, non-biological process that scientists haven't yet thought of.

So, in addition to coming up with ideas for what life might look like on alien planets, scientists must also come up with ways that non-living processes could create those same signatures. Scientists are now working hard to think up new examples of these "false positives," in an effort to avoid a misstep when the data start to appear. Because perhaps the only thing worse than not finding life elsewhere in the universe, would be thinking we'd found it, and then having it taken away. [Signs of Alien Life Will Be Found by 2025, NASA's Chief Scientist]

Oxygen and life

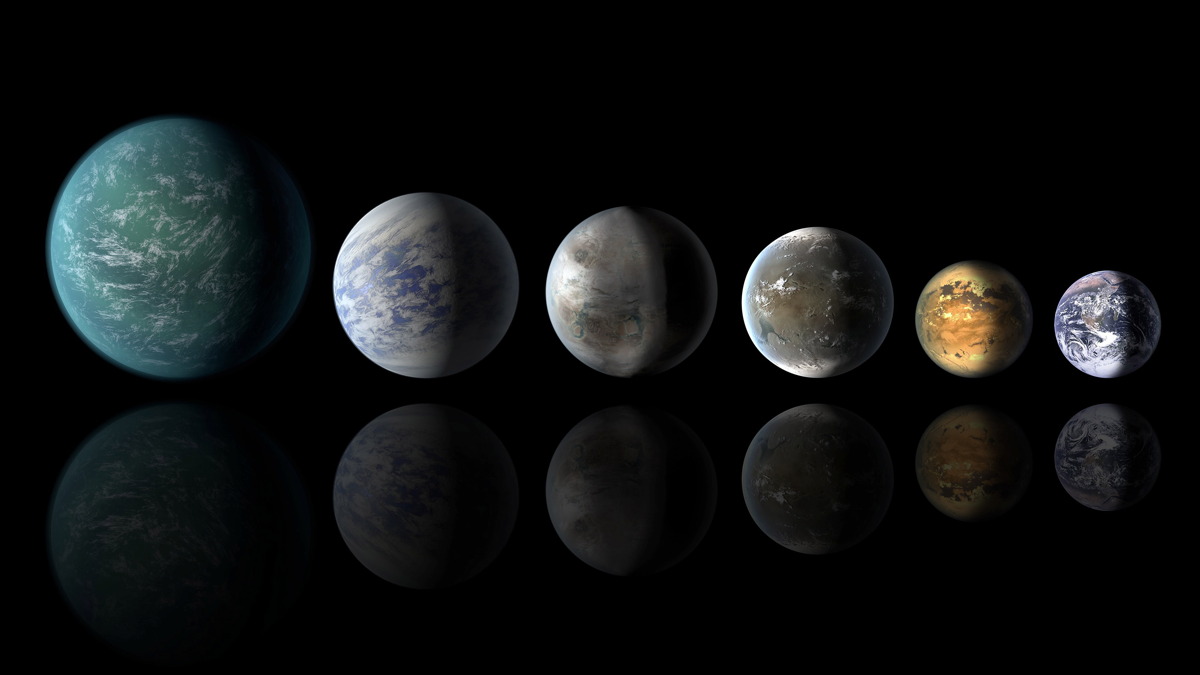

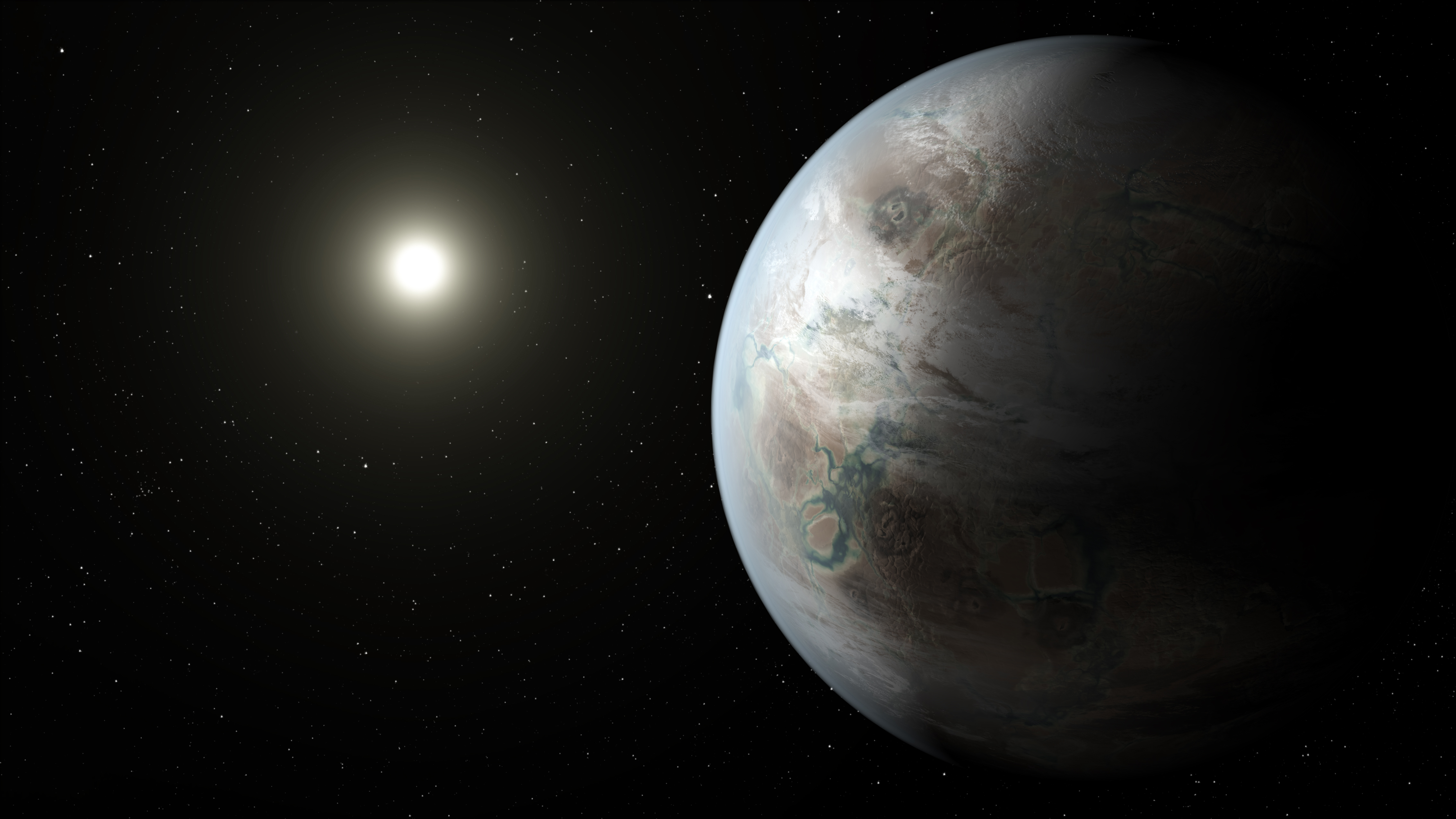

Scientists are continually on the hunt for potentially habitable worlds. Ideally, they'd like to find planets that look a lot like Earth: rocky, roughly the same size, orbiting a star similar to our own, and with a surface temperature that's not too hot or too cold for liquid water. (So far, no planets quite fit this bill, although there is one strong candidate). But if scientists then got a glimpse at the atmosphere of such a planet, or even a fuzzy look at its surface, how would those scientists determine if that planet was habitable, or inhabited?

That's the question that drives the work at the Virtual Planetary Laboratory (VPL), a multidisciplinary research collective consisting of 50 researchers at 20 different institutions. Victoria Meadows, a professor of astronomy at the University of Washington, is the VPL's principal investigator.

"How much do we really know about planetary processes, and can we discriminate them from biological processes on a planetary scale?" Meadows told Space.com. "It's a challenge. It's one of the biggest challenges facing humanity. It's one thing to be able to take the measurements and another thing to be able to understand what they're telling you.

"I think that's the philosophy of VPL: We need to do the science in advance of this and try to figure out as best as possible what are the signs we should be looking for, what kinds of measurements do we need to make, and most important, how are we going to get fooled?" she said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For many years, oxygen was thought to be the key to finding life on other planets. The Earth's atmosphere has a large supply of oxygen that is created almost entirely by biological beings. As such, it is considered a so-called "biosignature." Plants create oxygen, of course, but the bulk is thought to have come from certain types of bacteria that have lived on the planet for more than 2 billion years.

"Oxygen has been kind of put on a pedestal for a long time now as being sort of the most robust biosignature," Meadows said.

In the last five or six years, Meadows, and other scientists working with the VPL, have come up with four separate ways that oxygen could build in the atmosphere of a potentially habitable world through completely non-biological processes.

"People say, 'Oh, well, isn't that disappointing because you thought you had this perfect biosignature,' and now we have to be a little more careful,'' Meadows said. But by studying false positives, Meadows says scientists can figure out what information is needed to rule them out.

For example, very hot planets (likely too hot for life) may have oxygen in their atmospheres that is created by sunlight breaking up the water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Detecting large amounts of steam in the planet's atmosphere, therefore, is a good way to identify this process as the source of the oxygen.

"Working with these false positives lets us know, if you want to reduce the false positives, to do things like choose this type of target instead of this one, and also look for this type of gas instead of oxygen," Meadows said.

"It's like college students and pizza," said Shawn Domagal-Goldman, a researcher at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and a member of the VPL. "If you see college students and pizza in the same room at the same time, you know there's a pizza delivery truck nearby or a pizza shop nearby. Because college students tend to consume pizza pretty rapidly. It's the same with these biosignatures: The fastest production mechanism is biology."

Domagal-Goldman said he hasn't seen any convincing false positives for both oxygen and methane in an atmosphere, at least in concentrations high enough that they would be visible across interstellar space.

"So right now, that is the strongest biosignature that we have for the remote detection of life, at least for the next generation of telescopes," he said. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

Despite the added complication of false positives, finding a potentially habitable planet with oxygen in its atmosphere would still be a dream come true for scientists. Oxygen is the best-studied biosignature out of the hundreds of thousands of different chemicals that living organisms are known to produce on Earth (most in such small quantities they would never be detectable from afar).

"If we see oxygen, we'll definitely be jumping up and down, and we know exactly how to proceed," said Sara Seager, a professor of planetary science and physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "[With oxygen] we know exactly how to proceed. We know which false positive scenarios we think are out there and we would work really hard on those. We can get more observations if we have whatever telescope we need. And we're all good to go."

But considering that life on other planets could produce a totally different balance of chemicals than any of the life-forms on Earth, the odds seem stacked against such a straight-forward finding.

"The thing is, we can't guarantee anything in advance. I mean, we have to see that planet and see what's there," Seager said. "Some things are going to be very obvious, most things will be totally not obvious. So it's less of what we know and more like how lucky we're going to be getting."

A future telescope

After years of full-time research on planets and their climates, Domagal-Goldman has stepped into a position at NASA where he is spending part of his time serving as a sort of liaison between the scientific community and the people who are designing and building telescopes. As the community develops a better sense of what to look for in exoplanet atmospheres, he conveys those wish lists to the engineers who come back and tell him what's possible technically and financially.

One project he's working on is a proposal to add an instrument called a "starshade" to the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), which will study exoplanets and dark energy. The starshade would block the light from a distant star, making it easier to see the light reflected off the planets (similar to how blocking out the light from the sun with a hat makes it easier for the wearer to see things on the ground). The WFIRST telescope is scheduled to launch in the early to mid-2020s.

The James Webb Space Telescope, hailed as the successor to Hubble, is scheduled to launch in 2018 and will also provide new information about exoplanets. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), will serve as a successor to the highly successful Kepler Space Telescope, and identify hundreds or thousands more exoplanets in the universe.

None of these telescopes were built explicitly to observe the atmospheres of exoplanets, although the researchers say it is possible that each of them may provide such data for a few potentially habitable alien worlds. (In order for these telescopes to make those measurements, the planet and star have to be lined up in just the right way, so it's difficult to say exactly how many samples they might collect). So the scientific community is already looking ahead to a telescope that would collect data on the atmospheres of dozens of potentially habitable planets.

Currently called the High-Definition Space Telescope (HDST), this space-based observatory would snap images with a resolution 25 times higher than Hubble. A recent report on the new telescope promises that it will study the atmospheres of dozens of rocky planets orbiting their parent stars at a distance where liquid water might form. The tentative timeline indicates that the telescope could launch in the 2030s.

"James Webb and TESS, we definitely have a shot at finding something, but it's definitely tough," Seager said. "But only HDST will really nail the problem."

The technology needed to accomplish HDST's goals is achievable, the team says, but it is still in development. Detecting an exoplanet's atmosphere is extremely difficult, and costly, and the data might be too complex for scientists to determine with any certainty if those planets are home to life. But until interstellar travel becomes a reality, or an intelligent alien civilization makes itself known, studying exoplanet atmospheres may be the only shot for humanity to find out if life exists beyond our solar system.

"That's why we're doing it. I mean we're getting up every day and working hard. Every day I work on TESS in one way or another," Seager said. "We're only doing that because we believe there's a chance."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter