NASA's New Horizons Pluto mission should leave a rich scientific legacy, and could help spur future ambitious exploration efforts throughout the solar system, researchers say.

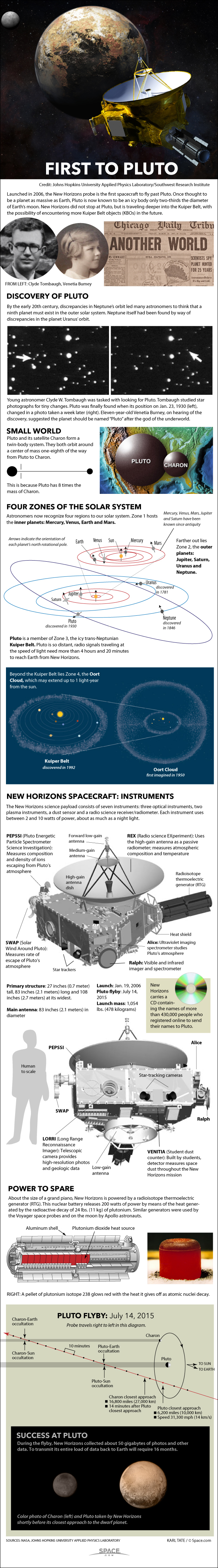

New Horizons conducted the first-ever Pluto flyby on July 14, collecting reams of images and data about the dwarf planet and its five moons.

The spacecraft's observations are already revolutionizing researchers' understanding of Pluto and other bodies in the faraway Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune's orbit. The scientific bounty will keep growing, because the vast majority of New Horizons' data has yet to come down to Earth — and the probe will probably zoom past a second, much smaller Kuiper Belt object (KBO) in 2019 as part of an extended mission. [New Horizons' Pluto Flyby: Complete Coverage]

The enormous public interest in the Pluto flyby also demonstrates that people love space exploration, especially missions that do new things or study little-known worlds or realms, New Horizons principal investigator (PI) Alan Stern told Space.com.

"I hope that New Horizons and Pluto have become an accelerant to space exploration," said Stern, who's based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

"Here's a mission run by an individual PI — small team, five times less money than [NASA's] Voyager [program] — and we lit the world on fire," Stern added. (New Horizons' total cost is about $720 million.) "What if you did human exploration in a way that lit people on fire on a 100-times bigger scale? It would be Earth-shattering."

The solar system's third realm

American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930. For a long time thereafter, the frigid world was regarded as an oddball. After all, it was the Kuiper Belt's lone known resident.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But about two decades ago, that perception began changing in a big way. Scientists started finding other KBOs, and it became clear — especially after the 2005 detection of Eris, which is about the same size as Pluto — that the dwarf planet is just the best-known of many icy bodies in the solar system's planetary "third realm." (The first realm is the zone of rocky planets, while the second is the abode of the gas giants such as Jupiter and Saturn.)

"I am most excited about this whole mission as sort of our only chance to get a view of what a Kuiper Belt object looks like — or two of them, two different-sized ones — and to sort of get an impression," said Mike Brown, a planetary astronomer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena who led the team that discovered Eris (and many other objects beyond Neptune, including Sedna).

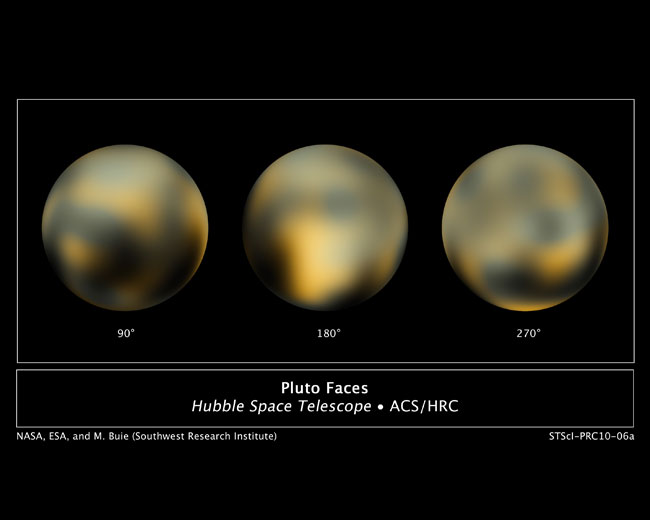

"Even before the flyby, we knew a lot about Pluto; we knew a lot about the Kuiper Belt; we had a lot of theories about what the observations that we have tell us," Brown, who is not a part of the New Horizons team, told Space.com. "And now we can start to really fill in reality with some of those pictures." [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

Active icy worlds?

Those pictures of Pluto and its moons have surprised most planetary scientists. The photos depict ice mountains and glaciers on Pluto and large, deep canyons on Charon, the dwarf planet's largest satellite. Some of the Pluto and Charon terrain imaged by New Horizons features few or no craters, suggesting that both worlds have been geologically active in the very recent past.

"It's been an amazing adventure, because Pluto looks to be a very active body," said Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., who is also not a New Horizons team member. (Last year, Sheppard and colleague Chadwick Trujillo of the Gemini Observatory in Hawaii announced the discovery of 2012 VP113, an object that lies much farther from the sun than Pluto does.)

"That's an eye-opener," Sheppard told Space.com, explaining that many scientists had thought Pluto and other KBOs have probably been "dead" internally for eons, lacking the energy source required to sustain geological activity.

New Horizons' imagery "is really making us have to go back to the drawing board to try to figure out what could be creating all of this activity," Sheppard said.

The mechanism must be different from that of other icy active worlds such as Saturn's moon Enceladus and the Jupiter satellite Europa, which are tugged hard by their giant parent planets, researchers say.

"Somehow the engine in Pluto is still running after four billion years, and nobody I know in the geophysics world knows how to make that happen," Stern said.

It's worth noting, however, that Brown is not convinced that Pluto has been active in the recent past. There is no evidence of recent mountain-building, and the dwarf planet's flowing ices don't require an internal energy source, he said.

Furthermore, Pluto's atmosphere and its icy plains are made of the same stuff, Brown said; when surface ices sublime, they go up into the atmosphere.

"So we know that many meters of ice have disappeared over the course of time, so the smallest craters will just ablate away due to the atmospheric loss," Brown said. "As the frosts move around on the surface, they probably degrade the surface in some way that we don't really understand." [Fly Over Pluto's Mountains and Ice Plain (Video)]

More to come

All of this discussion and debate is based on a tiny fraction of New Horizons' dataset. The probe won't finish beaming home all of its flyby images and measurements until late 2016, Stern has said.

And then there's that potential second flyby. Next year, the New Horizons team plans to ask NASA to approve and fund an extended mission, which would send the probe streaking past a KBO that's just a few dozen miles wide in 2019. (The spacecraft's handlers have two possible bodies in mind; they have not yet announced which one they'd target.)

Whichever small KBO is chosen likely formed close to its present position, whereas Pluto probably coalesced near the giant-planet region and was booted out to the Kuiper Belt, Sheppard said. Furthermore, he added, smaller KBOs are more pristine and primitive than Pluto and therefore provide a better glimpse at the raw materials that built the planets 4.5 billion years ago.

"The true mission is only half over," Sheppard said of New Horizons. "Linking the materials that we find in the Pluto system to these much smaller objects is going to really open our eyes to what the planets are made of."

Spurring exploration

"I'm told that we created the biggest bang for exploration in anybody's memory," perhaps going all the way back to NASA's Apollo moon missions, Stern said.

Such intense global interest and excitement bodes well for future exploration efforts — both robotic and human — that aim to do new things, he added. Stern hopes the enthusiasm and the lessons learned from it could make possible a Charon lander, which would study both that world and nearby Pluto from orbit.

But a return to the Pluto system "should be in parallel with [rather than substitute for] more exploration," Stern said, citing a manned journey to Mars as another desirable project.

For his part, Brown would love to get up-close looks at other distant bodies, especially Quaoar, a KBO about half the size of Pluto that he and Trujillo discovered in 2002. Quaoar represents a sort of transition point between Pluto and Charon, possessing some characteristics of both worlds, Brown said.

But Brown isn't optimistic that a mission to Quaoar — which lies even farther from Earth than Pluto does — will launch anytime soon.

"We just don't have the resources to visit all the interesting places in the solar system, and these at the edge of the solar system are just the hardest to get to," Brown said. "So I have resigned myself to never seeing any of these things that I discovered up close in my life. I suspect that's a reasonable prediction."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.