Apollo Moon Rocket Engines Recovered by Amazon CEO Preserved for Display

Two and a half years after an expedition led by the CEO of Amazon.com raised them off the ocean floor, the historic rocket engine parts that launched NASA astronauts on at least three missions to the moon are now preserved for museum display.

The conservation team at the Cosmosphere International SciEd Center and Space Museum (formerly known as the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center) in Hutchinson, Kansas completed researching and stabilizing the 25,000 pounds (11,340 kg) of Saturn V F-1 engine parts in June.

The mangled and twisted Apollo artifacts were recovered by a privately-financed effort organized by Amazon.com's Jeff Bezos more than four decades after the engines were used in the launches of the first, second and fifth manned moon landings. [See photos of the Apollo moon rocket engine salvage]

"There are some small unassigned parts that we will finish the conservation on, but [all of] the major artifacts in the collection are complete," Jim Remar, the Cosmosphere's president and chief operating officer, told collectSPACE in an interview on Monday (Aug. 3). "The final process in the treatment was applying a protective coating."

As they were found

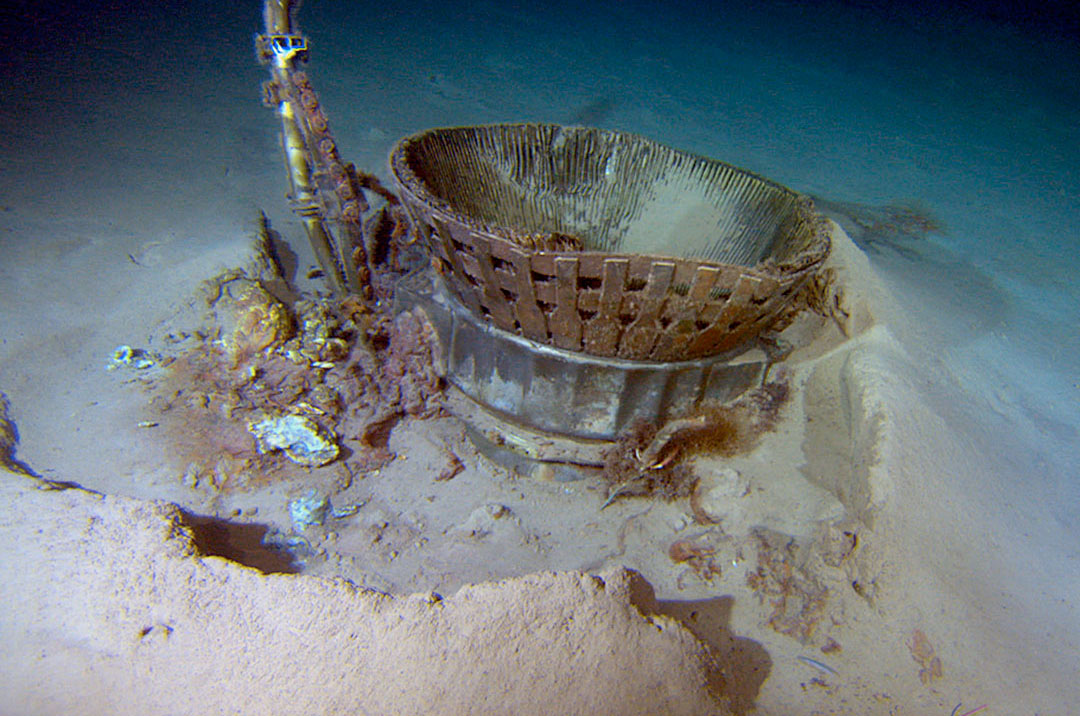

Bezos Expeditions surprised the world in March 2012 by announcing success in its up-to-then secret search to find the F-1 engines where they sunk some 14,000 feet (4,300 meters) below the Atlantic Ocean surface. Almost exactly a year later, Bezos again made international headlines by revealing that the same team had raised parts for several engines off the seafloor.

The components from the 19-foot-tall (5.8 m) engines were delivered to the Cosmosphere's SpaceWorks conservation facility, where the museum had earlier restored the Apollo 13 command module "Odyssey" and the ocean-recovered sunken Mercury capsule "Liberty Bell 7."

But instead of working to restore and reassemble the F-1 engines to their original launch condition, the conservators purposely strove to conserve the parts in order to preserve their complete history. [Apollo Saturn V F-1 Rocket Engines Explained (Infographic)]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"With a conservation, the end objective is to preserve the artifacts as they are," stated Remar. "The artifacts have a story and life. We didn't want to do anything that changed their look or appearance because we felt that would take away some of the story."

After accelerating the Saturn V to more than 6,000 mph (9,600 km/h) and pushing the rocket to more than 40 miles high (64 km), the engines then dropped back to Earth for a violent splashdown. Their impact with the ocean ripped the F-1 engines apart like tin cans.

"With this project, we truly wanted to preserve the artifacts as they were when they were recovered off the bottom of the Atlantic," Remar explained.

Exposing their history

To ensure that the artifacts survived on display however, the Cosmosphere team needed to remove a good deal of the corrosion on the exterior of the parts, which modified their appearance.

"We did not want to try to remove every last stain or every last appearance of rust and we wanted to try to keep the color as original to when they were found as possible. But there is differently a difference," Remar noted.

"The artifacts indeed do look different – but not drastically so," he added.

In addition to stabilizing the engine parts, the preservation also uncovered some of their history. The Cosmosphere's team discovered markings that tied the parts to flights on Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 in 1969 and to Apollo 16 in 1972.

"We were able to identify part numbers and serial numbers as we got deeper into the treatment process," Remar said. "There was a stencil painted on one of the Apollo 12 thrust chambers that was still visible, so we were able to identify that via the stencil. But other components were [discerned by] finding the part number and serial number."

The conservators found a thrust chamber, a liquid oxygen (LOX) dome and injector plate, a turbo pump and a heat exchanger from Apollo 11, the historic mission that landed Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon. There were also two thrust chambers and a LOX dome with an injector plate from Apollo 12 and a heat exchanger, a turbine and inlet manifold from Apollo 16.

"And then we're fairly certain one of the thrust chambers is from Apollo 13," Remar noted.

In the end, there was only one of the thrust chambers and a turbo pump that were not able to be linked to a mission. The conservators were also unable to establish a flight for the coiled spaghetti-like remains of the only engine nozzle that was returned to the surface.

"We untangled all the linear feet of tubing from the nozzle but didn't unbend them," Remar stated. "We did conserve them though, so they are preserved and the corrosion has been removed."

Learn where the recovered and now conserved Apollo F-1 engines are going on display — click through to collectSPACE to continue reading.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2015 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.