Drones in Space! NASA's Wild Idea to Explore Mars (Video)

A team of NASA engineers wants to put drones on Mars. These flying robotic sentinels could reach more of the Martian surface, and possibly solar system moons or the dark, sunless craters on asteroids.

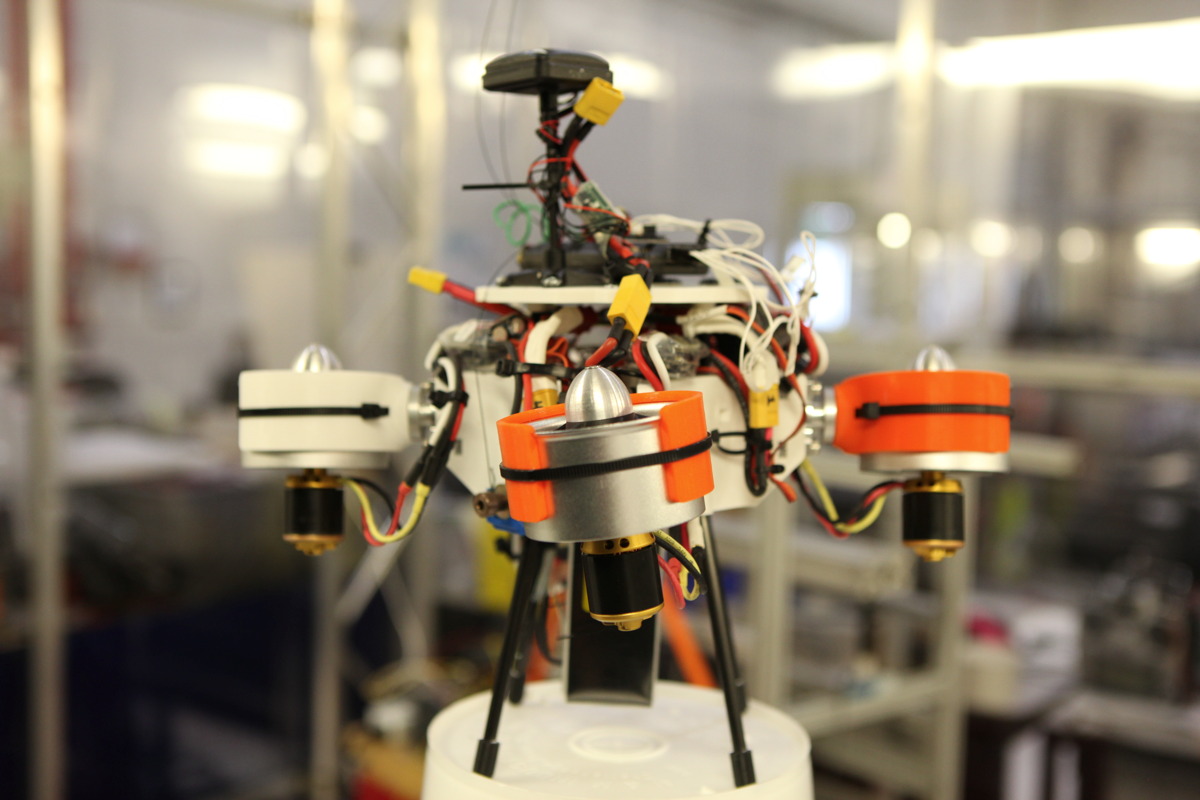

Autonomous quadcopters — the four-propeller flying craft commonly called drones— are fast, flexible, use little power and can get into (and out of) tight spaces. But they work only with an atmosphere to propel through. Now, the Swamp Works team at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida is developing a dronelike robot that works in dark, low- or no-atmosphere environments, and can recharge itself by returning to its lander mothership.

"This is a prospecting robot," Rob Mueller, senior technologist for advanced projects at Swamp Works, said in a statement. "The first step in being able to use resources on Mars or an asteroid is to find out where the resources are. They are most likely in hard-to-access areas where there is permanent shadow. Some of the crater walls are angled 30 degrees or more, and that's far too steep for a traditional rover to navigate or climb." [Watch: NASA's Tiny Helicopter Drone for Mars]

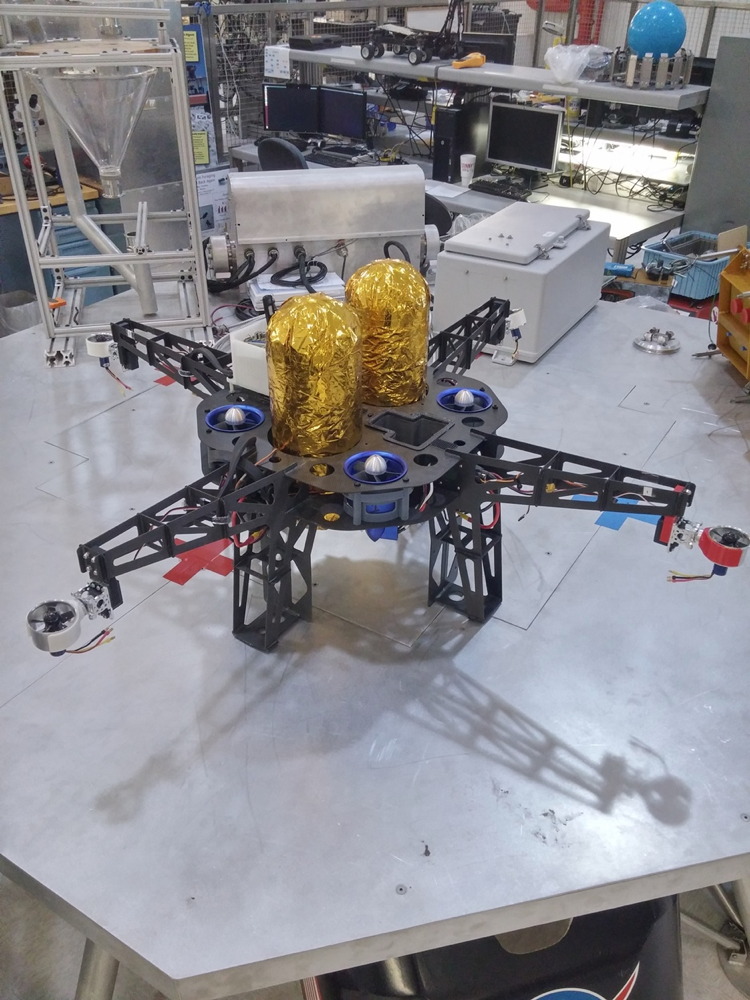

The new machines are called Extreme Access Flyers. Instead of rotors, they use jets of oxygen gas or water vapor to move around, whichever gas is available on the planet or asteroid the robots are exploring. With that fuel, they can zip around and forage for soil samples in areas inaccessible to traditional landers. The final version would be small enough to bring several to the surface on a lander, and they would carry enough fuel to get where they needed to go, the craft's developers say.

"It would have enough propellant to fly for a number of minutes on Mars or on the moon, hours on an asteroid," Mike DuPuis, aerospace engineer and co-investigator of the project, said in the statement.

The Swamp Works laboratory is already swarming with models to test the technology, ranging from a 5-foot (1.5 meters) quadcopter, likely the size of the final craft, to tiny, palm-sized flyers. The large flyer is used to test out movement over different terrain, borrowing a test site built for the SUV-sized Morpheus moon lander. Researchers use the smaller flyer to test maneuvering and software control by exploring inside a 10-foot by 10-foot cube (3 m by 3 m).

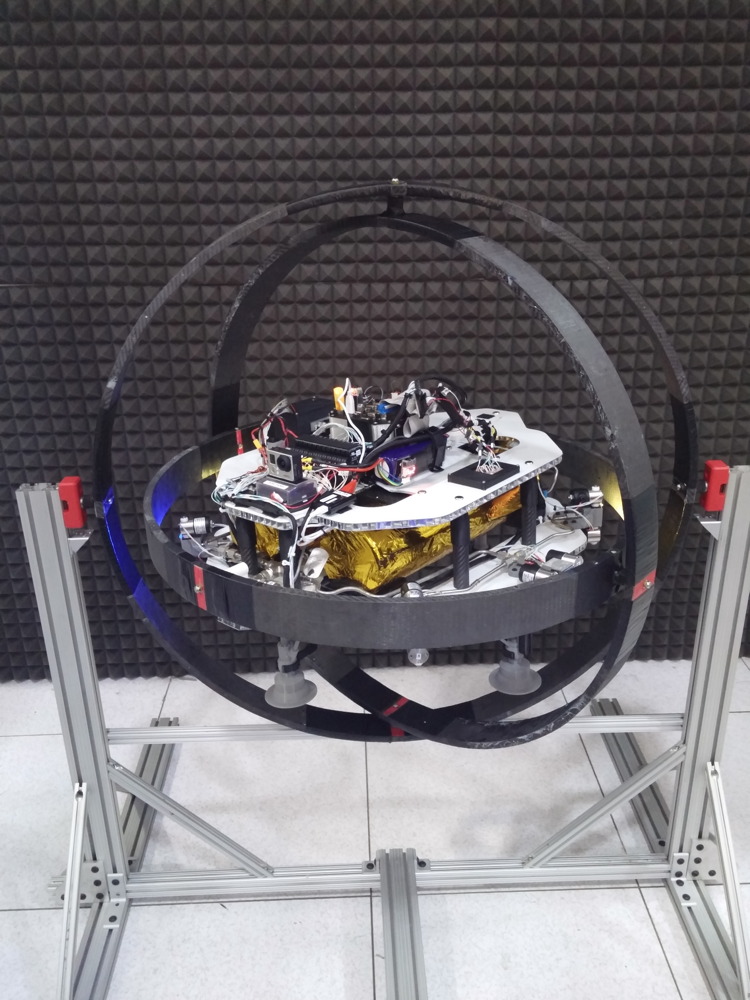

Researchers suspend another small flyer inside a frame that allows it to maneuver as if it hangs in zero gravity; that flyer propels itself with liquid nitrogen, and its twists and turns are re-created on the surface of a virtual asteroid. The final craft will combine autonomous exploration with mapping and laser guidance to get around the changing terrain and find its way home.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The flight-control systems of commercially available small, unmanned, multi-rotor aerial vehicles are not too dissimilar to a spacecraft controller," DuPuis said. "That was the starting point for developing a controller."

Once on the surface of a planet or other object, the flyers could carry one tool at a time to target locations to take small samples of about 7 grams (0.2 ounces) of material. Over the course of several trips, the flyers would get a complete geological picture of an area, NASA officials said.

Similar flyers could also grab samples in toxic or radioactive areas on Earth for measurement, Mueller said. And the craft could explore inaccessible tubes formed by the flow of lava, on Earth and off. Mueller suggested that a large lava tube, pre-mapped by such an explorer, could even provide shelter for humans on the surface of Mars.

"We're an innovations lab, so in everything we do, we try to come up with new solutions," Mueller said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.