Why Magnetars Should Freak You Out

Paul Sutter is a research fellow at the Astronomical Observatory of Trieste and a visiting scholar at The Ohio State University's Center for Cosmology and Astro-Particle Physics. Sutter is also host of the podcasts "Ask a Spaceman" and "RealSpace," and the YouTube series "Space In Your Face." He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

I'll be honest: Magnetars freak me out. But to get to the "why," I have to explain the "what." Magnetars are a special kind of neutron star, and neutron stars are a special kind of dead star.

They're easy enough to make — if you're a massive star. All stars fuse hydrogen into helium deep in their cores. The energy released supports the stars against the crushing weight of their own gravity and, as a handy byproduct, provides the warmth and light necessary for life on any orbiting planets. But eventually, that fuel in the core runs out, allowing gravity to temporarily win and crush the star's core even tighter.

With the greater pressure, it becomes helium's turn to fuse, combining into oxygen and carbon, until the helium, too, gives out. That's where our own sun gets off the fusion train, but more massive stars can keep on chugging along, climbing up the periodic table in ever more intense and short-lived reaction phases, all the way up to nickel and iron.

Once that solid lump of nickel and iron forms in the stellar core, a lot of things go haywire — fast. There's still a lot of star stuff left in the atmosphere, pressing into that core, but further fusion doesn't release energy, so there's nothing left to prevent collapse.

And collapse it does: The nickel and iron nuclei (yes, just nuclei; don't even think about entire atoms at these temperatures and pressures) break apart. They just can't handle this nuclear mosh pit. Stray electrons get shoved into the nearest protons, converting them to neutrons. The neutrons … stay neutrons. And those neutrons are mighty good at preventing further collapse, for reasons I’ll explain in a bit. The infalling gas, trying to crush the core into oblivion, bounces off that neutron core and goes kablamo! (Note: I don't know what it actually sounds like.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The neutron ball

What happens during the supernova event is an exciting discussion for another day. What we're concerned with now is the leftovers: a soupy, ball-like mixture of neutrons and a few straggler protons. This ball is supported against its own weight by "degeneracy pressure," which is a fancy way of saying that you can only pack so many neutrons in box — or, in this case, a ball. It may seem obvious that neutrons, well, take up space, but things didn't have to turn out this way. It's this degeneracy pressure that causes the big bounce that puts the super in supernova.

I should note that, if there's still too much stuff left hanging out around this leftover neutron ball, the weight can overwhelm even degeneracy pressure. And now, look what you've done: You've gone and made a black hole. But that, too, is another story. We wouldn't want to be like our poor star and get overwhelmed.

The neutron ball — which I should now call by its proper name, a neutron star — is weird. Seriously, that's the best word I can find to describe it. Neutron stars are basically city-size atomic nuclei, which makes them among the densest things in the universe. The pressure of gravity inside these stars has squeezed apart even atomic nuclei, allowing their bits to float freely.

It's mostly neutrons down there — hence the name — but there are also a few surviving protons floating around. Normally, those protons would repel one another, being like-minded charges and all, but they are forced close together as the Strong Nuclear Force tries to bunch them up with their fellow neutrons.

The neutron star's interior is a complicated dance of physics under extreme conditions, resulting in very odd structures. The oddity starts near the surface, with blobs of a few hundred neutrons that are best described as neutron gnocchi. Below that, the neutron blobs glue together into long chains. We have entered the spaghetti layer. Underneath that, at even more extreme pressures, the spaghetti strands fuse side by side and form lasagna sheets. Under it all, even neutron lasagna loses its shape, becoming a uniform mass. But that mass has gaps in it, in the form of long tubes. At last: delicious penne.

I wish I were making these names up, but physicists must be especially hungry people when coming up with metaphors.

Did I mention the spinning? Oh yes, neutron stars spin, up to a few hundred times per second. Let all of this sink in for a bit: An object with such strong gravity that "hills" are barely a few millimeters tall, rotating with a speed that could rival your kitchen blender. We're not playing games anymore.

Neutron stars are scary

All this action — the insane densities, the complicated structures, the ridiculously fast rotation rates — means that neutron stars carry some pretty nasty magnetic fields. But don't magnetic fields require charged particles, and aren't neutrons neutral? That's true, smartypants, but there are still a few protons hanging out in the star, and at these incredible densities, physics gets … complicated. So, yes: Neutron stars, despite their name, can carry magnetic fields.

How strong? Take a star's normal magnetic field, and squish it down. Every time you squish, you get a stronger field, just as you get higher densities. And we're squishing something from star-size (a million kilometers or miles, take your pick) to city-size (like, 25 kilometers — just 15 miles). Plus, with all the interesting physics happening in the interiors, complex processes can operate to amplify the magnetic field, so you can imagine just how strong those fields get.

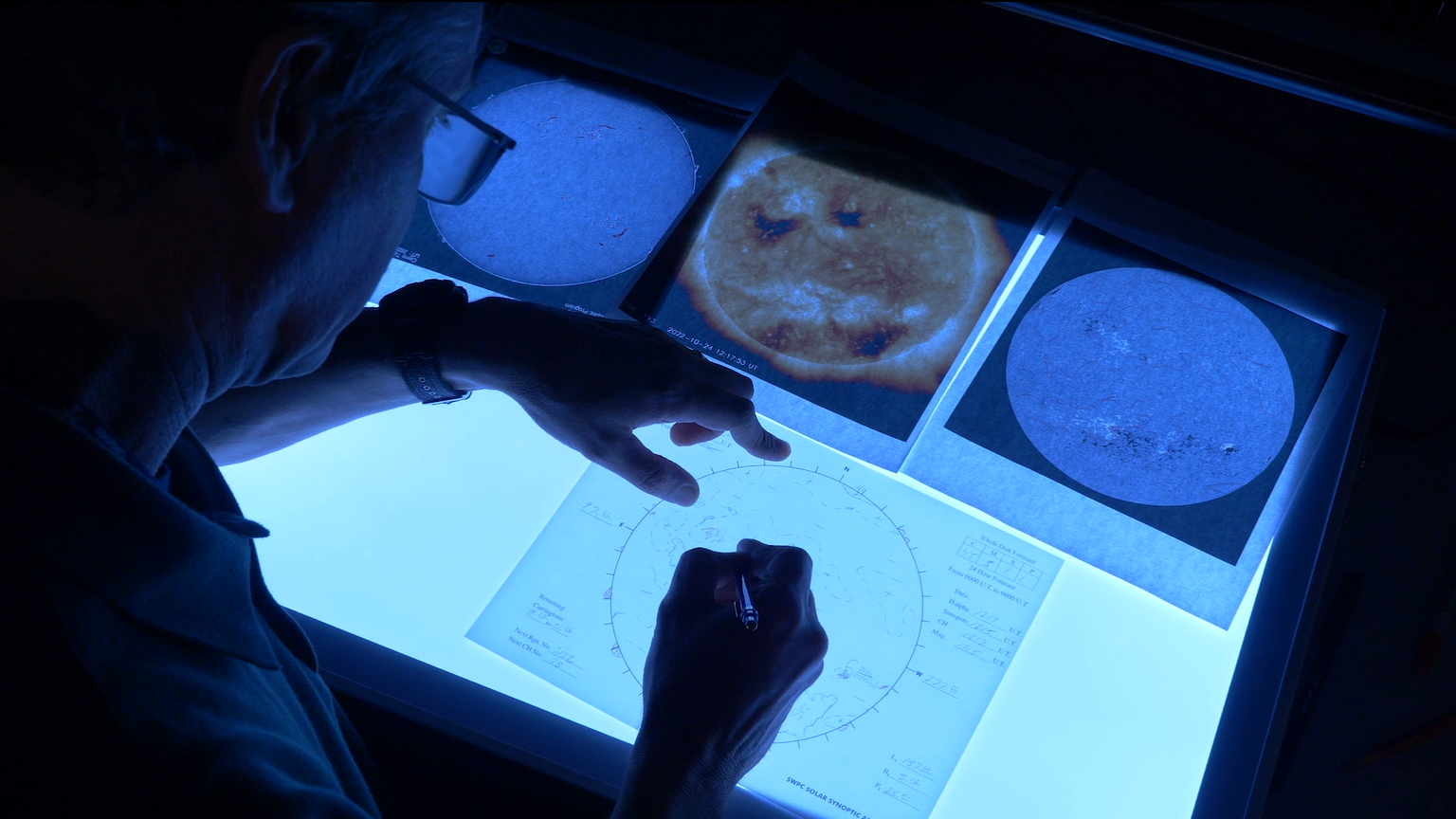

Actually, you don't have to imagine, because I'm about to tell you. Let's start with something familiar: the Earth's magnetic field. That's around 1 gauss. It’s not much different for the sun: a few to a few hundred gauss, depending on where on the surface you are. An MRI? 10,000 gauss. The strongest human-made magnetic fields are about a few hundred thousand gauss. In fact, we can't make magnetic fields stronger than a million gauss or so without our machines just breaking down from the stress.

Let's cut to the chase: A neutron star carries a whopping trillion-gauss magnetic field. You read that right — "trillion," with a "t."

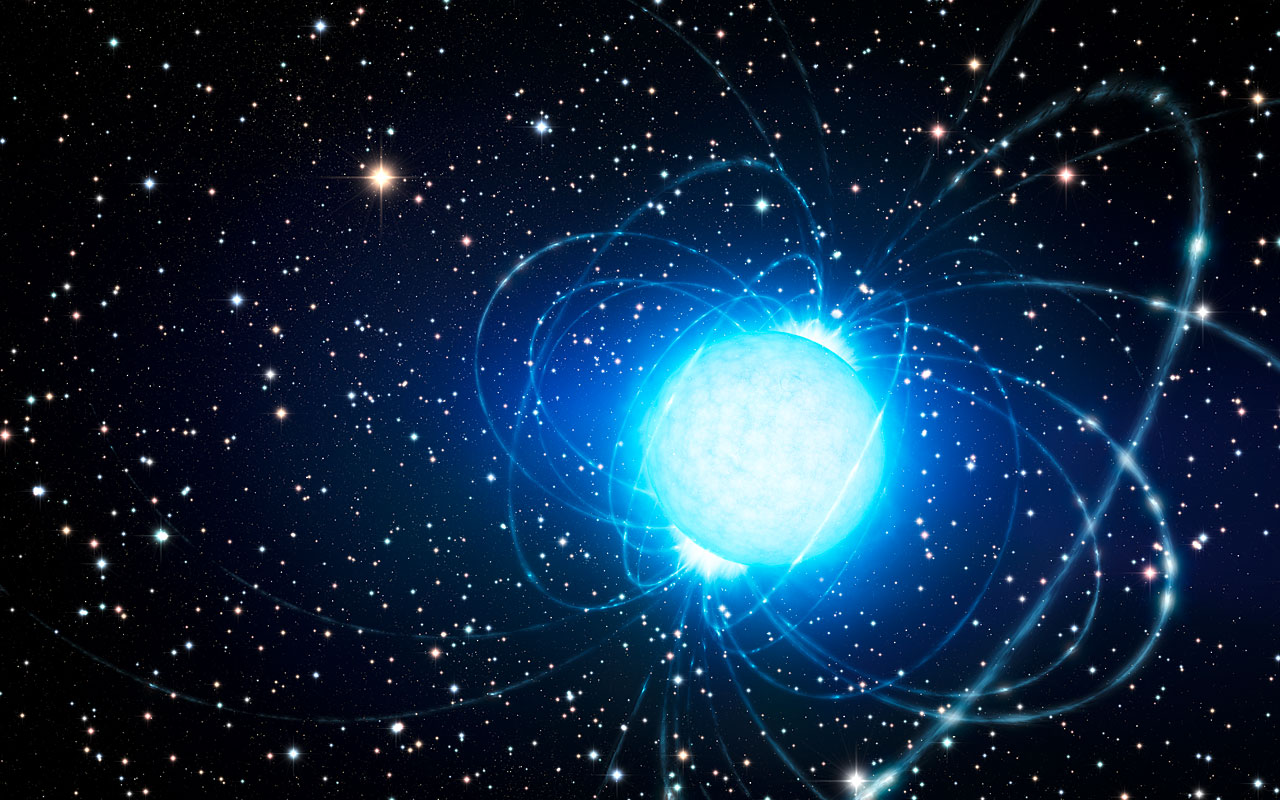

Enter the magnetar

Now, we finally get to magnetars. You may guess from the name that they're especially magnetic: up to 1 quadrillion gauss. That's 1,000 trillion times stronger than the magnetic field you're sitting in right now. That puts magnetars in the No. 1 spot, reigning champions in the universal Strongest Magnetic Field competition. The numbers are there, but it's hard to wrap our brains around them.

Those fields are strong enough to wreak havoc on their local environments. You know how atoms are made of a positively charged nucleus surrounded by negatively charged electrons? Those charges respond to magnetic fields. Not very much under normal conditions, but this ain't Kansas anymore, is it, Toto? Any unlucky atoms stretch into pencil-thin rods near these magnetars.

It doesn't stop there. With the atoms all screwed up, normal molecular chemistry is just a no-go. Covalent bonds? Ha! And the magnetic fields can drive enormous bursts of high-intensity radiation. So, generally bad business.

Get too close to one (say, within 1,000 kilometers, or about 600 miles), and the magnetic fields are strong enough to upset not just your bioelectricity — rendering your nerve impulses hilariously useless — but your very molecular structure. In a magnetar's field, you just kind of … dissolve.

We're not exactly sure what makes magnetars so frighteningly magnetic. Like I said, the physics of neutron stars is a little bit sketchy. It does seem, though, that magnetars don't last long, and after 10,000 years (give or take), they settle down into a long-term normal neutron-star retirement: still insanely dense, still freaky magnetic, just…not so bad.

So, as scary as they are, at least they won’t stay that way for long.

Learn more by listening to the episode "What the heck is a magnetar?" on the "Ask A Spaceman" podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to Zowie Pinkerton for the great question inspiring this piece! Ask yours on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.