NASA Extracting Tanks from Retired Shuttle Endeavour for Use on Space Station

NASA's space shuttle Endeavour, retired and on exhibit in Los Angeles for the past three years, has been called back into service — or rather, parts of it have — for the benefit of the International Space Station.

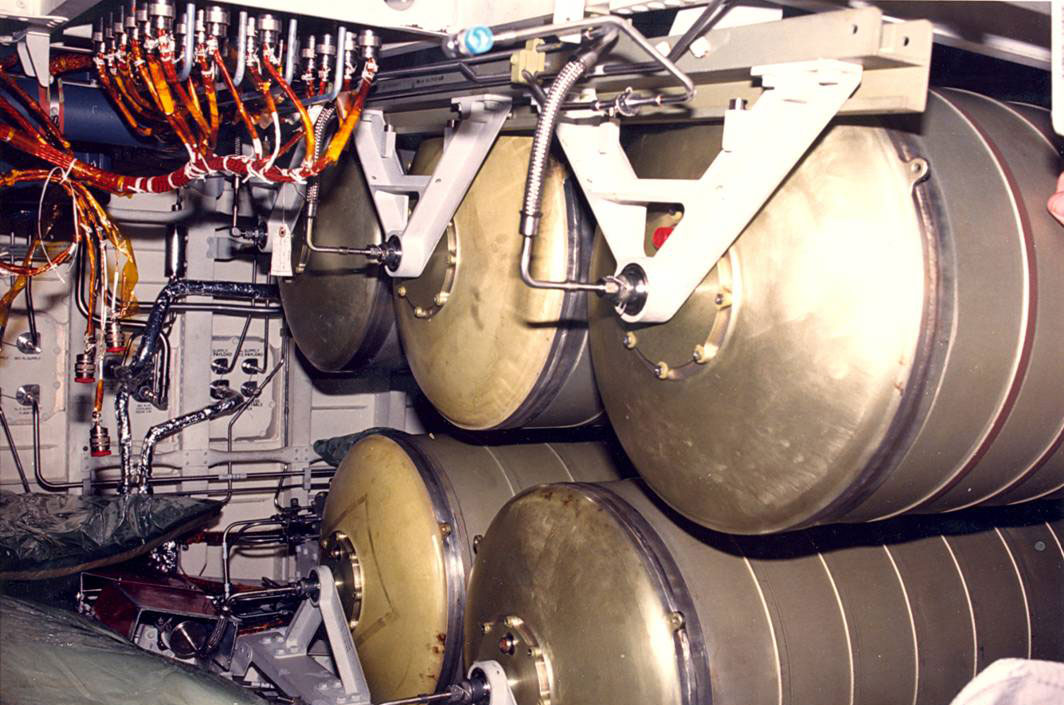

A NASA team working this week at the California Science Center will remove four tanks from deep inside the winged orbiter to comprise a water storage system for the space station. The reactivated artifacts are intended to help free more crew time for science operations onboard the orbiting outpost by reducing the astronauts' involvement in refilling their water reserves.

"The ISS [International Space Station] program has been steadily increasing the amount of crew time dedicated to science and technology development [onboard the station] through initiatives like the water storage system," NASA told Endeavour's curators at the California Science Center, according to information shared exclusively with collectSPACE.com. [Photos: Space Shuttle Endeavour at the California Science Center]

Reusing the orbiter's tanks, rather than manufacturing new hardware, will "reduce the overall cost of building the water storage system," NASA said.

When space shuttle Endeavour was still flying, the same tanks were used not only to provide drinking water for the orbiter's crew but to also fill storage bags to provide water for the space station's crew. Similar duffle-like, soft bags are still in use today to hold the water processed through the orbiting outpost's recycling system, which purifies the crew's urine, perspiration and other waste water so that it is drinkable again.

But refilling those bags is more time consuming than if the station were to have a more capable reserve. Endeavour's water tanks can hold a total of 300 liters, enough for about 25 to 27 days.

Taking out the tanks

Each of Endeavour's potable water tanks measures 3 feet long by 1.3 feet wide (0.9 by 0.4 m) and weighs 40 pounds empty (18 kg). Together with a single waste water tank of similar dimensions, they are located underneath the crew cabin's lower living space called the mid-deck. [Space Shuttle Endeavour: 6 Surprising Facts]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Workers will enter the orbiter, which is exhibited inside the science center's Samuel Oschin Display Pavilion, through the same hatch that was used by the astronauts to enter and exit the space shuttle before launch and after landing. The hatch is normally kept closed as the center's visitors are not allowed to tour inside the vehicle.

Using a lift to reach the hatch, the NASA workers will gain access the tanks through the mid-deck's floor. Under the seats where mission specialists sat for launch and landing is a locker that held the lithium hydroxide (LiOH) canisters used to clean the orbiter's air of carbon dioxide. Unbolting and lifting out that container offers a pathway to drop down below the deck.

From there, it is the relatively simple task of detaching the plumbing and electrical connectors that lead to each tank and unbolting the four tanks themselves from the rails that held them in place.

The pavilion will remain open to science center visitors as the work completed, which is expected by Friday. The four tanks will then be shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

How and when the new water storage system will be flown to the space station was not specified.

Preservation vs. program

In 2011, at the end of its 30-year shuttle program, NASA handed over Endeavour to the California Science Center. The L.A. museum and educational complex is working to exhibit the orbiter standing upright, mounted as it was for launch with the last remaining external tank built for flight and a pair of solid rocket boosters.

The exhibit, which will stand in the science center's yet-to-be-built Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center, is expected to open in 2018.

Before delivering Endeavour to California, NASA prepared the orbiter to be safe for public exhibit and removed some of its parts, like the shuttle's three main engines, for future use with its heavy-lift rocket, the Space Launch System. But the agency needed the science center's permission to remove the four water tanks, as the space shuttle is now the museum's property. [NASA's Space Shuttle from Top to Bottom (Infographic)]

"Since the Smithsonian keeps the reference copy of the orbiter – Discovery is more intact than either Atlantis or Endeavour, we are okay with giving up things that serve a useful purpose to NASA that don't affect the appearance or function of the vehicle," stated Dennis Jenkins, project manager for Endeavour's display.

"Supporting an active program [like the station] seems like a worthy cause," he added.

Discovery, at the National Air and Space Museum Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia, will be retaining its water tanks. Atlantis, which is still NASA property, recently had its tanks extracted from its display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex to support the same station water storage system.

It is not without precedent for NASA to retrieve its former parts from museums to support its on-going programs, but it is rare.

In 2013, for example, the space agency borrowed from the Smithsonian a gas generator out of an Apollo Saturn V F-1 engine and fired up another retrieved from an F-1 engine displayed at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama, in support of developing a new engine.

NASA also temporarily removed parts from the prototype orbiter Enterprise, now on display at the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum in New York City, to help in its tests following the loss of the space shuttle Columbia in 2003.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2015 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.