Editor's note: To find out more about the rare supermoon lunar eclipse of Sept. 27-28 and how to see it, visit: Supermoon Lunar Eclipse 2015: Full 'Blood Moon' Coverage .

The first "supermoon" lunar eclipse in more than three decades will grace Earth's skies this month, as will a partial solar eclipse that most of the world will miss.

The supermoon total lunar eclipse, which occurs on Sept. 27, features a full moon that looks significantly larger and brighter than usual. It will be the first supermoon eclipse since 1982, and the last until 2033, NASA officials said in a newly released video.

The total lunar eclipse will be visible to observers throughout the Americas, Europe, Africa, western Asia and the eastern Pacific Ocean region. [How Lunar Eclipses Work (Infographic)]

A partial solar eclipse will take place two weeks before this special supermoon, on Sept. 13, but the earlier event will be visible only to skywatchers in southern Africa (as well as penguins, leopard seals and the other wildlife of Antarctica).

"Supermoons" occur because the moon's orbit around Earth is elliptical rather than circular. While the moon's average distance from our planet is about 239,000 miles (384,600 kilometers), the natural satelite roams as far away as 252,000 miles (405,600 km) at "apogee" and gets as close as 226,000 miles (363,700 km) at "perigee."

A supermoon is a full moon that occurs at, or very near, perigee and appears abnormally big in the sky as a result. In fact, supermoons appear about 14 percent larger and 30 brighter than apogee full moons, which are also known as "minimoons."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Supermoon eclipses are special; they've occurred just five times since 1900 (in 1910, 1928, 1946, 1964 and 1982), NASA officials said in the new video. "Normal" lunar eclipses are much more common. In fact, an observer at any particular location around the globe can expect to see a total lunar eclipse about once every 2.5 years on average.

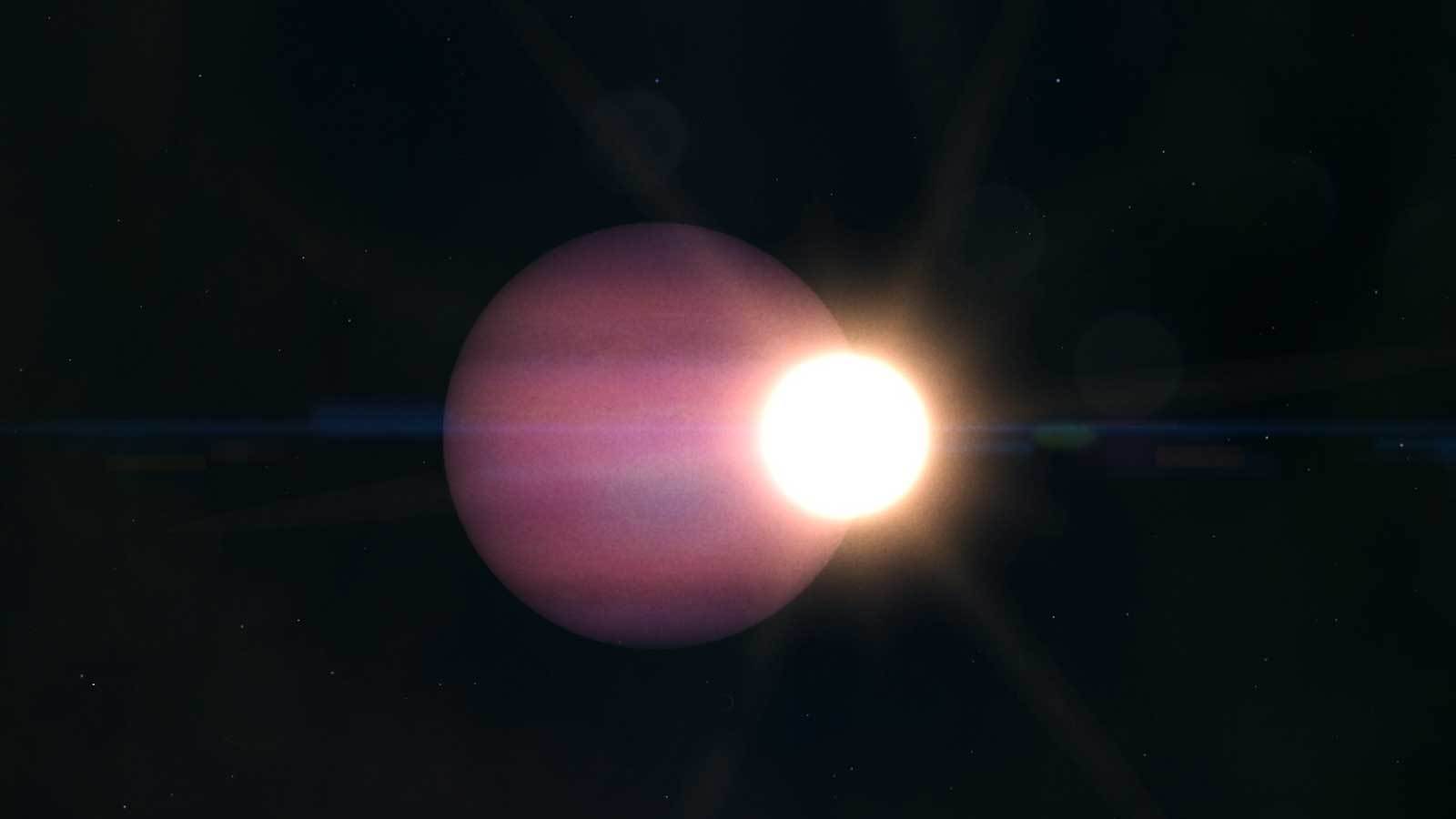

Lunar and solar eclipses are both caused by alignments of the moon, Earth and sun. In the case of a lunar eclipse, the Earth is the middle of this line and the moon passes into the planet's shadow. But the moon doesn't go completely dark during total eclipses; rather, it often turns a reddish hue because it's hit by sunlight bent by Earth's atmosphere. For this reason, total lunar eclipses are often referred to as "blood moons."

With a solar eclipse, the moon is in the middle of the Earth-moon-sun line and blots out all or part of the solar disk from an Earth observer's perspective.

If you live in southern Africa or plan to travel to the region to view the Sept. 13 partial solar eclipse, a word of warning: NEVER look at the sun without proper eye protection, even during an eclipse; serious and permanent eye damage can result.

You can learn about safe eclipse-viewing strategies in this Space.com infographic.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing view of the supermoon lunar eclipse or any other night sky view that you would like to share with Space.com for a possible story or gallery, send images and comments in to managing editor Tariq Malik at: spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.