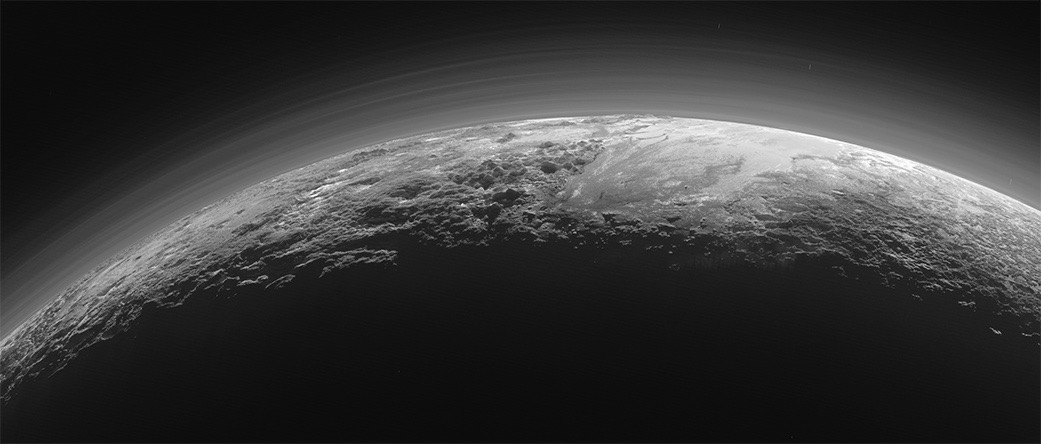

A spectacular new image from NASA's New Horizons spacecraft shows Pluto in an entirely new light.

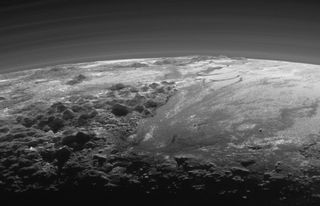

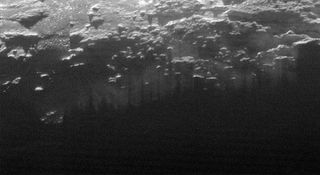

The photo, which New Horizons took during its epic July 14 flyby of Pluto, captures a gorgeous sunset view. Towering ice mountains cast long shadows, and more than a dozen layers of the dwarf planet's wispy atmosphere are clearly visible.

"This image really makes you feel you are there, at Pluto, surveying the landscape for yourself," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement today (Sept. 17). "But this image is also a scientific bonanza, revealing new details about Pluto's atmosphere, mountains, glaciers and plains." [See more Pluto photos by New Horizons]

New Horizons captured the panorama, which covers a stretch of land 780 miles (1,250 kilometers) across, using the probe's wide-angle Ralph/Multispectral Visual Imaging Camera on July 14, just 15 minutes after closest approach to Pluto.

The spacecraft turned back and looked toward the sun, snapping the photo at a distance of just 11,000 miles (18,000 km) from the dwarf planet, NASA officials said. (At closest approach, New Horizons was about 7,800 miles, or 12,550 km, from Pluto's surface.)

The result was a new perspective on Pluto's Norgay Montes and Hillary Montes, two ranges of ice mountains that rise up to 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) above the dwarf planet's frigid surface. The backlit photo also reveals new details about Pluto's nitrogen-dominated atmosphere, showing many different layers, extending from ground-bound fog to wispy tendrils more than 60 miles (100 km) up.

"In addition to being visually stunning, these low-lying hazes hint at the weather changing from day to day on Pluto, just like it does here on Earth," Will Grundy, leader of New Horizons' composition team from Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, said in the same statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

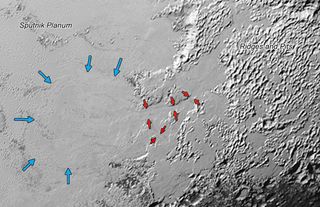

The new panorama and other recently downloaded New Horizons images also shed light on how ice — likely made of nitrogen and other materials rather than water — flows into a vast, flat glacial plain known as Sputnik Planum. Some of Sputnik Planum's ice apparently evaporates, gets deposited in a region of rough terrain to the east and then flows back down into the plain as glaciers, via a system of valleys.

These glaciers are similar to those seen in Greenland and Antarctica here on Earth, researchers said.

"We did not expect to find hints of a nitrogen-based glacial cycle on Pluto operating in the frigid conditions of the outer solar system," said Alan Howard of the University of Virginia, a member of the mission's geology, geophysics and imaging team. "Driven by dim sunlight, this would be directly comparable to the hydrological cycle that feeds ice caps on Earth, where water is evaporated from the oceans, falls as snow and returns to the seas through glacial flow."

"Pluto is surprisingly Earth-like in this regard, and no one predicted it," Stern added.

New Horizons beamed the new backlit panorama home to mission control on Sunday (Sept. 13), and NASA released the photo today.

The world can expect to see many more stunning new views from the Pluto flyby over the coming year or so. New Horizons relayed just 5 percent of its flyby data back in the immediate aftermath of the close encounter, keeping the vast majority on board for later transmission. That data dump began in earnest earlier this month and is expected to take about 12 months, New Horizons team members have said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.