What can observers expect to see happen during a lunar eclipse? Check out our guide to learn about the different phases of this celestial event.

No enthusiastic skywatcher ever misses a total eclipse of the moon. People are often surprised by how beautiful and engaging the spectacle is. Because of this hypnotizing beauty, during the time that the moon is going into, and later emerging from, the Earth's shadow, secondary phenomena may be overlooked.

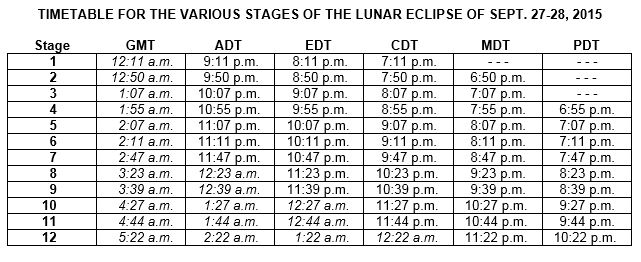

To help prepare for the upcoming supermoon lunar eclipse of Sept. 27 to 28, Space.com’s Joe Rao, a veteran of sixteen total lunar eclipses — has prepared an eclipse chronology. It is likely that not all of the events mentioned will occur, because no two eclipses are exactly alike. But many will, and those who know what to look for have a better chance of seeing them! [Supermoon Lunar Eclipse: When and How to See It]

In the above timetable, all un-italicized times are for p.m. on September 27. Times in italics are a.m. on September 28. When dashes are provided, it means that the moon has not yet risen above the horizon. The eclipse will be visible to more than half the planet — check here to see if it will be visible in your area.

Many European countries are currently observing "summertime," which is 1 or 2 hours ahead of GMT.

Newfoundland is 30 minutes ahead of Atlantic Daylight Time (ADT).

Puerto Rico is on Atlantic Standard Time, which is the same as Eastern Daylight Time (EDT).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Arizona is on Mountain Standard Time, which is the same as Pacific Daylight Time (PDT).

Alaska is 1 hour behind PDT; Hawaii is 2 hours behind PDT.

The various stages, fully described:

1) Moon enters penumbra: The shadow cone of the Earth has two parts: A dark, inner umbra, surrounded by a lighter penumbra. The penumbra is the pale, outer portion of the Earth's shadow. Although the eclipse officially begins when the moon enters the penumbra, this is in essence an academic event — you won't see anything unusual happening to the moon, at least not just yet. The Earth's penumbral shadow is so faint that it remains invisible until the moon is deeply immersed in it. We must wait until the penumbra has spread roughly 70 percent across the moon’s disk. For about the next 40 minutes, the full moon will continue to appear to shine normally, although with each passing minute it is progressing ever deeper into the Earth's outer shadow.

2) Penumbral shadow begins to appear: Now the moon has progressed far enough into the penumbra that it should be evident on the moon's disk. Start looking for a very subtle, light shading to appear on the moon's left portion. This will become increasingly evident as the minutes pass; the shading will appear to spread and deepen. Just before the moon begins to enter the Earth's dark umbral shadow, the penumbra should appear as an obvious smudge, or tarnishing, of the moon's left portion.

3) Moon enters umbra: The moon now begins to cross into the Earth's dark central shadow, called the umbra. A small, dark scallop shape begins to appear on the moon’s left-hand (eastern) limb. The partial phases of the eclipse begin; the pace quickens, and the change is dramatic. The umbra is much darker than the penumbra and is fairly sharp-edged. As the minutes pass, the dark shadow appears to slowly creep across the moon's face. At first, the moon's limb may seem to vanish completely inside of the umbra, but much later, as it moves in deeper, you'll probably notice it glowing dimly orange, red or brown. Notice also that the edge of the Earth's shadow projected on the moon is curved. Here is visible evidence that the Earth is a sphere, as deduced by Aristotle from Iunar eclipses he observed in the fourth century B.C. Almost as if a dimmer switch were slowly being turned down, the surrounding landscape and deep shadows of a brilliant, moonlit night begin to fade away.

4) 75 percent coverage: With three-quarters of the moon's disk now eclipsed, that part of it that is immersed in shadow should begin to very faintly light up — similar to a piece of iron heated to the point where it just begins to glow. It now becomes obvious that the umbral shadow is not completely dark. Using binoculars or a telescope, observers can usually see that its outer part is light enough to reveal lunar seas and craters, but the central part is usually much darker, and sometimes no surface features are recognizable. Colors in the umbra vary greatly from one eclipse to the next. Reds and grays usually predominate, but sometimes observers see browns, blues and other tints.

5) Less than 5 minutes to totality: Several minutes before (and after) totality, the contrast between the remaining pale-yellow sliver and the ruddy-brown coloration that is spread over the rest of the moon's disk may produce a beautiful phenomenon known to some as the Japanese Lantern Effect.

6) Total eclipse begins: When the last of the moon enters the umbra, the total eclipse begins. How the moon will appear during totality is not known. Some eclipses are such a dark gray-black color that the moon nearly vanishes from view. At other eclipses it can glow a bright orange. The reason the moon can be seen at all when totally eclipsed is that sunlight is scattered and refracted around the edge of the Earth by our atmosphere. To an astronaut standing on the moon during totality, the sun would be hidden behind a dark Earth outlined by a brilliant red ring consisting of all the world's sunrises and sunsets. The brightness of this ring around the Earth depends on global weather conditions and the amount of dust suspended in the air. A clear atmosphere on Earth means a bright lunar eclipse. If a major volcanic eruption has injected particles into the stratosphere during the previous couple of years, the eclipse is very dark. But, as of this writing, no such major eruption has happened, so the betting is that this eclipse will be relatively bright. [Lunar Eclipse Beauty: How to Photograph the Moon]

7) Middle of totality: The moon is now shining anywhere from 10,000 to 100,000 times more faintly than it was just a couple of hours ago. Since the moon is moving to the south of the center of the Earth’s umbra, the gradation of color and brightness across the moon’s disk should be such that its upper portion will appear darkest, with hues of deep copper or chocolate brown. Meanwhile, its lower portion — that part of the moon closest to the outer edge of the umbra — should appear to be the brightest, with hues of reds, oranges and even perhaps a soft bluish-white color.

Those who are observing away from bright city lights will notice that many more stars are visible in the later night sky than they were earlier.

The darkness of the sky is impressive. The surrounding landscape has taken on a somber hue. Before the eclipse, the full moon looked flat and one dimensional. During totality, however, it will look smaller and three dimensional — like some weirdly illuminated ball suspended in space.

Before the moon entered the Earth's shadow, the temperature on parts of its sunlit surface hovered as high as 266 degrees Fahrenheit (130 degrees Celsius). Since the moon lacks an atmosphere, there is no way that this heat could be retained; it escapes into space as the shadow sweeps by. Now that it's in shadow, the temperature on the moon has dropped to minus 146 degrees F (99 degrees below zero C). That's a drop of 412 degrees F (229 degrees C) in less than 90 minutes!

8) Total eclipse ends: The emergence of the moon from the shadow begins. The first small segment of the moon begins to reappear, possibly followed again for the next several minutes by the Japanese Lantern Effect.

9) 75 percent coverage: Any vestiges of coloration within the umbra should be disappearing now. From here on, as the dark shadow methodically creeps off the moon's disk, it should appear black and featureless.

10) Moon leaves umbra: The dark central shadow clears the moon’s right hand (western) limb.

11) Penumbral shadow fades away: As the last, faint shading vanishes from the moon's right portion, the visual show comes to an end.

12) Moon leaves penumbra: The eclipse "officially" ends, as the moon is completely free of the penumbral shadow.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo of the supermoon lunar eclipse and want to share it with Space.com for a story or gallery, send images and comments in to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.