Mars Gets More Habitable with Water Discovery, Scientists Say

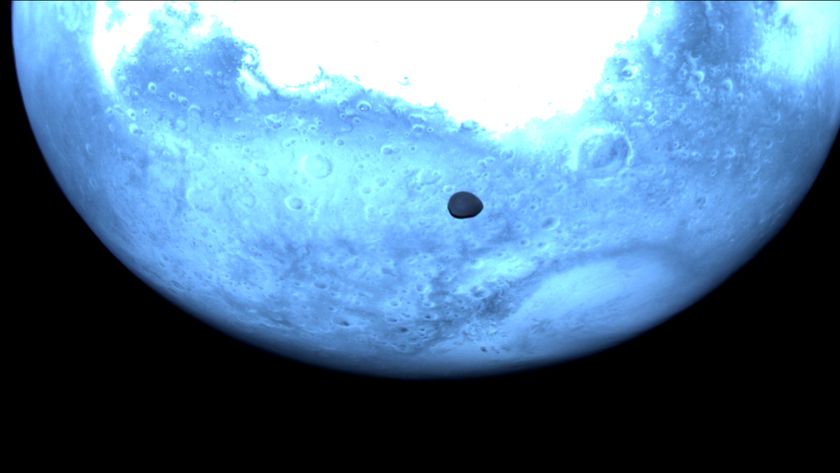

The discovery of liquid (albeit very salty) water on Mars may suggest that the Red Planet is more habitable than previously thought, according to scientists.

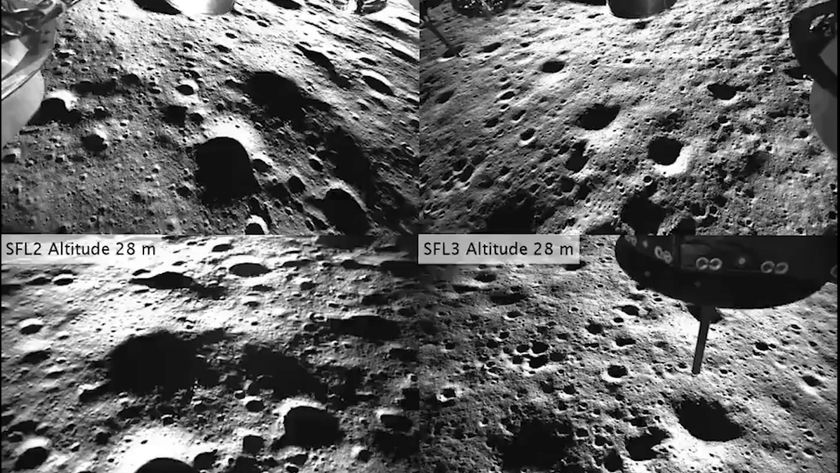

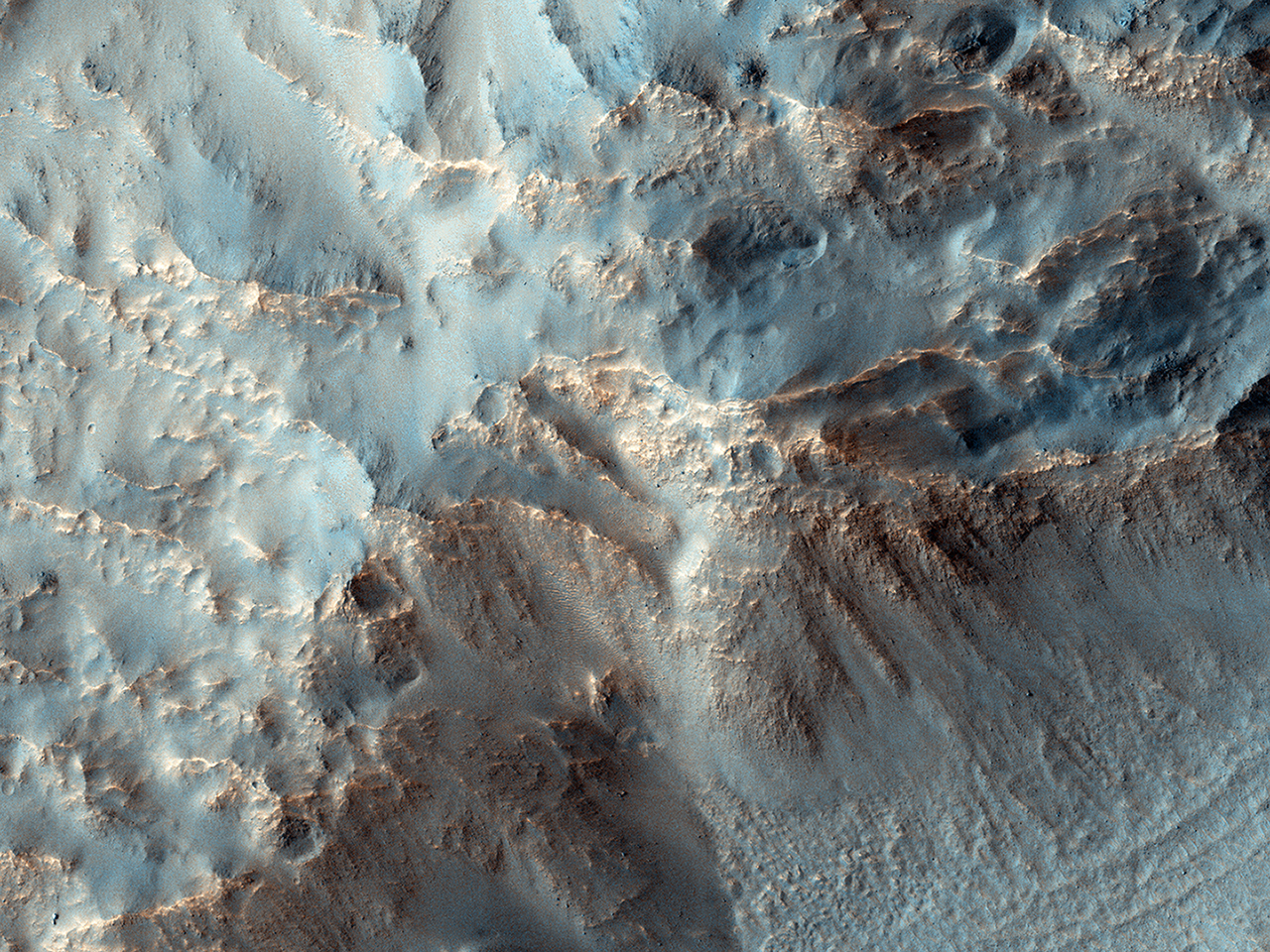

Strange, dark streaks that run down the sides of hills on the surface of Mars are formed partly by the presence of liquid water, scientists announced today (Sept. 28). Using NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), the researchers say they now have strong evidence that salty water soaks the planet's surface soil, perhaps even flows down the slopes, and creates the dark streaks.

"Water, as I'm sure many of you have heard us say on multiple occasions, is an essential ingredient for life," said Mary Beth Wilhelm, a planetary science researcher at the NASA Ames Research Center, in a NASA briefing earlier today (Sept. 28). "Our results may point to more habitable conditions on the near surface of Mars than previously thought." [Flowing Water on Mars: The Discovery in Pictures]

The surface of Mars is, for the most part, extremely inhospitable to life. But life on Earth has proven again and again to be incredibly tenacious. There are life-forms that can survive incredibly hot and cold temperatures, extreme doses of radiation, and highly salty pools of water. But the authors of the new study, which was published online today (Sept. 28) in the journal Nature Geoscience, said they can't yet make any direct comparisons between the saltwater found on Mars and environments on Earth.

"The potential habitability by Earth-like microbes is unclear," said Wilhelm, who is one of the authors on the paper announcing the new finding. "To assess habitability, we would first need to determine how cold and how concentrated the brine is."

The dark streaks of saltwater found on Mars are technically referred to as "recurring slope linea," or RSLs. Michael Meyer, lead scientist for the Mars exploration program at NASA, noted during the briefing that similar-looking streaks have been observed in Antarctica.

"The difficulty is that something that looks the same doesn't mean it is the same, so we don't know if it's the same mechanism [causing the streaks]," Meyer said. "But at least we have something that looks similar, so that's being studied."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The question of whether life can survive in the Martian brines is further complicated because most of the brines are seasonal. They appear in the early Martian spring but then disappear in the Martian autumn and winter months, said Alfred McEwen, principal investigator for the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) aboard MRO, who also spoke during the NASA briefing.

RSLs at the equator of Mars can be observed year-round, McEwen said, but they move with the sun throughout the year (so they appear on the slopes that get the most sunlight). Because the RSLs don't constitute a permanent feature, any life-forms they might support would have to find a way to survive when the water disappears (there are life forms on Earth that can go into hibernation during periods of drought).

Another relevant question in the search for life in these RSLs is the source of the water. The authors of the new research said their leading hypothesis is that the water is absorbed from the Martian atmosphere. MRO detected a type of salt called a perchlorate, which can suck water out of the air — a process called deliquescence. But, the scientists noted that it's possible that the water is coming from subsurface supplies.

"If I were a microbe on Mars, I would probably not live near one of these RSLs," said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. "I would want to live further north or south, at higher latitudes, quite far under the surface, where there's a freshwater glacier. We only suspect those places exist, and we have some scientific evidence that they do. And that's a subject of future exploration, when we can find subsurface ice that's a few meters or deeper below the surface and that's fresh water. And I think that's going to be a very exciting area of exploration in the future."

Grunsfeld noted that these RSLs would likely receive attention in future Mars rover missions and other studies of the Red Planet.

"I can't imagine that it won't be a high priority for the scientific community to send something … to go to these areas, and may have a life-detection capability to see if there's life there that's similar to [life on] Earth," he said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter